“I don’t hurt women.” That was a lie. He’d hit Annique hard enough to leave her doubled over, gasping. He had an ironic truth to give her though. “I’m not going to touch you.”

“Then I do not understand why you are here.”

“There are three men trying to kill you.”

“Many more than three, Robert.” She thought about that for a hundred yards, nibbling on grass, glancing at him keenly once in a while. “Do you know, I believe you are sincere. But it is not necessary. I am the old hand at this.” She took the grass stem out of her mouth and rolled it back and forth between her fingers. The fluffy head on the end went whirling out and out like some child’s toy. “You are…Oh, you are very tall and strong and brave and a good fighter. But these are entirely committed and evil men who pursue me. It is my own acts which have set them after me, not any concerns of yours. I would not like to see you get hurt.”

The idiot woman was worried about a husky brute of a man, instead of taking care of herself. “I don’t get hurt easily. May I give you a ride? Harding here…” He had no idea what Fletch called the horse. His Latin teacher at Harrow had been named Harding. “…would be happy to carry you.”

“You have not listened at all to what I say. I will tell you that England is an even stranger place than I had heard. I do not believe Englishmen toss aside all their concerns to walk to London with some woman they have met in an alley. It is not reasonable.”

Tricky, this business of lying to Annique.

“You remind me of someone I knew once. A woman.” He hoped the hesitation sounded like looking at old memories instead of inventing as he went along. “Not in England. She was French. I treated her badly, and I can’t go back and undo it.” That was close to the truth. What he’d already done to Annique ate at him like acid. Maybe regret came through in his voice. “It’s too late.”

“‘But that was long ago and in another country,’” she quoted softly, “‘and, anyway, the wench is dead.’” She darted another shrewd glance at his face. “I wondered why you studied me so strangely back there in the town.”

“You look like her.”

“I do not want to look like someone else. I have troubles enough of my own without a…a doppelgänger making more for me.”

Maybe it wasn’t convincing. He waited, remembering to keep his breath even. Making himself look at the horse, at the ground. Men telling lies like to look you in the face.

“I have made mistakes,” she said after a long time, “which haunt me at night and which I cannot erase.” She ran her thumbnail down the long stem of grass, frowning. “You saved my life. All the same, I cannot believe—”

“I was leaving Dover tomorrow.” Rational, logical Annique. Give her a practical, sensible reason, and it would convince her. “Headed home for a visit. To Somerset. I have to go through London anyway. I’d be glad of the company.”

He made himself stop there. When it came to lies, as Hawker always said, “Don’t embellish.”

“Ah. It is not so big a change, that, to leave one day early. To you it would seem like fate, perhaps, when I am presented under your nose. I am not inclined to believe such things myself, but I know many people who do.”

She looked out over the fields, thinking abstruse, clever Annique thoughts.

Take it on trust, Annique, just this once. Believe me. Lead me to the Albion plans. Make it easy for both of us.

Then she nodded. “I will travel with you to London, if this is what you must do to clean yourself of the past. I owe you that much. But Robert…you would be wiser to return to your ship and your family and forget this woman who has long since made her peace with God.”

“If I get you safely to London, that’s enough. That’s what I have to do.”

She must have caught the determination in his words, but it didn’t frighten her. Good. He was damned sick of frightening her.

“Bon. We will travel together then, till London. I will be grateful for the company.”

She turned her face to the north, to the length of road, measuring distances under the sky. He was seeing the real Annique Villiers at last. This was what she’d been for all those years, trailing across Europe in the raggle-taggle tail of the army, in boy’s clothing, nibbling something plucked from a field. A pair of larks sprang up from the field beside them and flew a complex pattern toward a stand of trees. She brightened, gazing after them, delighting in the moment, squirreling another memory away inside her.

“I will like England.” She started walking again. “I have been here only four hours, and already I have met three men trying to kill me and one who bought me whelks. For better or worse, this is not a country that ignores me.”

Nineteen

“I WILL SLIT HER THROAT.” HENRI’S FACE WAS marbled into an ugly map of bruises. His hand, on the tabletop, was swathed in white cloth.

“Ass! Do you think the English have no ears?” Leblanc glanced around. Fishermen stuffed themselves with onions and fried fish. At a table in the corner, a woman drank gin. No one was listening. “You will get your chance soon enough.”

“First, I will deal with him. I will gut him like a mackerel and leave him flopping in his blood.”

“As you did before?”

“No one reported this English spy was in Dover. How was I to expect—”

“Cease! You whine like a dog.” Leblanc hunched over his watered rum. His arm ached unbearably. He was in England, wallowing in this dockside filth, in danger. He might be stopped and questioned at any moment by stupid, clumsy British authorities. Annique had escaped him. This was Henri’s fault, every bit. “She goes to Soulier, in London, to tell him lies about me. He has been her objective all along. I am sure of it.”

“But she does not carry the papers. We could have stayed in France, if it is papers you want.” Henri doubtless thought he was clever.

“Forget the papers. What is important is that she dies. She must not reach Soulier.”

“We are in his territory. When he hears what we have done…”

“She is my agent, assigned to me. I can do what I like with an outlaw who crosses the Channel without my orders.” Leblanc finished the glass in one swallow. What he would not give for an hour in privacy with that bitch. One hour. “I have sent word to Fouché what she does. When the Directeur of the Secret Police supports me, I do not give a fart for Soulier. Faugh. Who can drink this?”

“There is brandy.” Henri looked for the serving maid.

“It is all pig wash. Rum, gin, beer, brandy—they are horse piss in this stink of a country. You will take six of the men and go east, along the coast. Send the others west. She is squatting by the fire in some fisherman’s hut, thinking she has outsmarted me.”

“Why would she hide in some small village where everyone peers and spies and chatters? She will go to London. To Soulier. When he learns we are in England—”

“Enough.” Leblanc slammed the empty glass on the table.

One fisherman, and then another and another, shot looks in their direction. The whore at the corner table hastily dropped a coin by her mug and left. Even the innkeeper eyed them with suspicion.

Leblanc held rage behind clenched teeth. He could not order these scum hauled into the street and beaten. He, Jacques Leblanc, friend of Fouché, had no power here. Everything…everything…was in ruins. He had lost any chance of the Albion plans. That bitch whore, Annique, would run to Soulier and complain. He should have killed her, her and Vauban, too, there in the inn at Bruges.

Henri would not cease. “I only say that we must watch the road to London—”

“I am not a fool, Bréval. I, myself, will watch the coaching inn to see if she takes the stage to London. You will search the coast. And you will not concern yourself with papers.”

The Albion plans were lost. The payment that should have been his—lost. His very life was threatened. Annique had many sins to pay for.

Any minute, she would learn of the death of Vauban. She must not reach Soulier and babble in his ear. “She is to be killed on sight. They need not be gentle.” Let her suffer a lifetime of pain in every second it took her to die.

“Soulier is fond of her. He will be furious.”

“When she is a corpse, it does not matter what Soulier is fond of.”

Twenty

IN THE LIGHT OF THE THIN NEW MOON, ROBERT groomed the horse Harding. He brushed his way with care and thoroughness from mane to withers to rump and tail. From bite to kick, as it were. She thought the horse Harding liked it. He looked smug.

“You are indulgent to that horse.” She watched the outline of him against a gray sky. “He has done no work whatsoever except to walk a little.”

“I like taking care of animals.”

She supposed a life surrounded by fishes and smuggled brandy would not allow time to care for livestock. “Is he from your home, the horse Harding? Perhaps one that your brother bred, who is so fond of horses?”

“Spence? No, Harding isn’t one of his. I picked Harding up in Dover. Spence would like him though. If I brought him home, he’d try to win him in one of his card games. He’d cheat, most likely, since it’s just family.”

“It must be interesting to have brothers and sisters. I have often thought so.”

For four long days Robert had laid his whole history out before her, like a gift. It was as if he’d waited all his life for the chance to tell his story to a grubby French spy walking on the dusty roads in Kent. She knew now of the house in Somerset where he had grown up, where his mother and father and the older brother Spence and a young sister still lived.

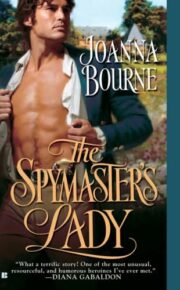

"The Spymaster’s Lady" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady" друзьям в соцсетях.