“He has taken Adrian’s knife away with him,” she said clearly. “How am I to cut vegetables?” She stared down the alley where Leblanc had disappeared.

Those were the first words he heard her speak in English. She had a beautiful voice—fluent and husky, the French of her buzzing under every syllable. A caress of a voice. The woman couldn’t breathe without enticing him.

“But I would not have wanted to cut vegetables with it, would I, if it had Leblanc’s blood upon it.” She put her fist over her mouth and began to giggle.

Battle nerves, that laughter. She’d need a wall behind her to hold her up for a while.

He’d lost his knit fisherman’s cap during the fight. He bent and picked it up and beat it on his trousers, watching her. She’d run as soon as she pulled herself together.

“He would not have wanted me to cut vegetables with it, in any case, the man who gave me the knife. He would be delighted where that knife is. He does not like Leblanc—my friend does not—the friend who has so many knives.” She pushed glossy strands of black hair off her forehead and peeked up at him. For the first time, he saw Annique looking out of her eyes.

She didn’t know him.

Frank and charming, pale as parchment, she smiled. “Thank you very much. Thank you very, very much.”

He played the black knit cap through his fingers and waited for her to recognize him. That would be the end of the joy in her. He’d drag her out of this maze of streets and wipe the brightness from her and carry her off to London. There was a bleak, nasty fight coming in a few minutes, inevitable as sunset. He’d win. She’d lose.

She ran her eyes over his face, his hair, his shoulders, the whole length of him in his smelly fisherman’s jersey and trousers. Appraising. Approving. She said, “It is a strange thing. I can speak five languages, and I cannot think of a single way to say how grateful I am that you have saved me.”

Why don’t you know me, Annique?

She trembled with the shocky aftermath of terror, and laughed, and thanked him politely again and again, and she didn’t know him at all.

My God. You’ve never seen me, have you? You don’t know my face. You don’t know the color of my hair or the shape of my nose. I could be anybody.

She didn’t know who he was. If he left her free, and followed her, she might lead him straight to the Albion plans.

Could it be done? The more he considered it, the better it sounded. She knew where the plans were. He was sure of it. Somehow, after that bloody debacle at Bruges, Annique had been left holding the Albion plans.

She didn’t bring anything from France. He’d been following her since she stepped out of the fishing boat at the docks, empty-handed. Could the Albion plans already be in England?

Where are the plans, Annique? Are you headed for them right now? Going to take them to Soulier, I bet.

If she led him to the plans…It was the cleanest way that could be. One instant of shock, and it would be over. No long, well-practiced interrogation. No poisoned intimacy as he stripped her secrets away, hour after hour. No clever, painless coercion that would leave them both feeling sick.

At Meeks Street, in his comfortable prison, he’d loosen her hold on the plans, inch by inch. He was expert. He’d take them from her. He’d get dirty fingerprints all over her soul, doing it.

He could leave her free. It was tempting on every level. If he left her free, he’d have days with Annique when she wouldn’t be his enemy. Maybe she’d keep looking at him like he was some kind of white knight. Maybe that was what he wanted.

She knows my voice. But I can change my voice.

Growing up in deepest Somerset, he and his brothers had run tame in the stable, copying the grooms’ speech and getting clouted for using it in the parlor. Broad Somerset still came easily to his tongue when he went home.

He pitched his voice deep and spoke in the familiar West Country cadence. “Are you hurt?” He didn’t sound like himself to his own ear.

“Not in the least, thank you. It is very brave of you to attack so many men, three of them, when they were armed.”

He shrugged. He wouldn’t talk much. She couldn’t recognize his voice if she didn’t hear it.

“You are modest as well. But it is because of you I am not gutted like a herring, for which I am unendingly appreciative. It is heroism on your part, to throw yourself into a fight with such eagerness, when you do not know me at all.”

“Anybody’d do the same.” He kept expecting the next word to wake her memory and tell her who he was.

“Perhaps. There is much altruism in the world.” She pushed herself away from the wall and staggered over to pick her shawl up from the dirt. “But it does not always arrive promptly and with such useful muscles. A friend gave me this, that her mother knitted for her.” She shook out the shawl. “It would have been found beside my body, if you had not come.”

He made a noncommittal noise. He could fool her for a day or two, if he was careful. That might be all he needed.

“I have been very lucky this morning, have I not? I cannot begin to think of how I will thank you.”

She smiled at him. If she kept being grateful to passing strangers, somebody was going to bundle her into a bedroom at the nearest inn and lock the door and let her prove exactly how grateful she was.

When she walked unsteadily down the alley, stumbling and setting her hand on the wall from time to time, he walked with her, keeping an arm’s reach away. He didn’t try to help. He didn’t lay a finger on her. A single touch, and she’d recognize him with her skin.

HER sense of direction had not deserted her. She backtracked down one long street and made a right turn, and they came to the small market square with wharves behind it. At the side was a line of stone benches. She sat and closed her eyes and felt the world spin around her. When she opened her eyes, the tall man in the black fisherman’s sweater was still there.

It overwhelmed her continually, the intensity of seeing. She could have counted the individual dark hairs upon his cheek, and every one of them was beautiful.

He wiped his hands upon his sweater that smelled so of fish and said, “You don’t look well.”

His accent was different from the English smugglers she knew. His voice grated harsh from his throat. That would be from those years at sea, probably, or heavy drinking ashore.

“I am fine.” But she shook in every fiber. It was good to have a clean place to sit. “It is only that I have been frightened to the core, you understand, thinking I would be killed, which could terrify anyone and is a thing I have never become used to.”

The sailor was a large man, and obviously strong as an ox, which was doubtless useful on boats. He might have been twenty-eight or thirty. His brown hair was cut close to his skull and lay in layers, like shingles. His eyes were a dark, colorless mixture of shades, like the sea itself, a sort of gunmetal gray. The lower half of his face was dark with stubble. None of this should have made him handsome, and yet, to her, he was.

She liked sailors, in general, and had spent much time chatting with them in various ports of Europe, discovering what they knew about coastal defenses and the movements of naval vessels. Most sailors were more talkative than this one.

“I will not bore you again with gratitude, but it is only because you have been capable and brave for me that I did not die today. If you will look away for the smallest time, I will take out my money, which I have hidden.” There was a tavern across the street. Near the docks of a city there is always a tavern. “That house does not appear respectable,” she said, being frank about the women who were inside it, “but the smell of its beer is good. I was traveling for a time with a man who would have called a mug of beer a ‘heavy wet,’ though he did not get around to teaching me that. I will buy you a heavy wet.”

“You will not buy me a drink. You shouldn’t have anything to do with that place, and you know it.” He considered her some more. “I’ll get us both something. Stay here. Don’t move, not an inch, till I get back.”

One corner of the market was full of food sellers, and that was his goal. She watched him stride through the crowd. He expected every man to step out of his way. And they did. His clothing might say able-bodied seaman, but his confidence spoke of command. He was first mate, she thought, or captain.

And, most likely, he was not exactly a fisherman. He walked confidently in this market of Dover. She had heard much of the English press gangs from her smuggler friends. The English navy would take any such man from the port towns, so tall and strong, with his hands marked with pine pitch and tar, and drag him off to their naval ships to be poor and uncomfortable. Unless he had powerful protection. The smugglers had great influence along this south coast of England.

Almost certainly he was an English smuggler like her friend Josiah. Smugglers were cunning and capable men and it was not altogether surprising she should owe her life to one. How interesting life in England was turning out to be.

He was so tall it was easy to follow his progress amid the booths of the market. He picked a stall, and the woman dropped her other customer like a three-day-old mackerel to hurry to serve him. She was old enough, that woman, that she should not have been so foolish for a pair of broad shoulders. Or perhaps she was not so foolish. When he left, he flipped her a silver coin, not asking for change.

He brought back whelks, held in a cone of broadsheet paper. They looked exactly like the ones she had eaten in the fisherman’s hut in St. Grue two days before, though these were English whelks. He carried also two mugs of tea, hooking the two handles with one finger very deftly. The tea contained milk in abundance and great heapings of sugar, neither of which she wanted, but he had saved her life for her and she would have happily eaten a bouquet of meadow grasses if that had been what he offered.

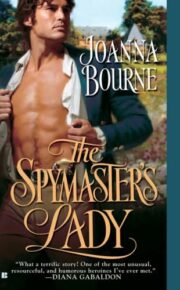

"The Spymaster’s Lady" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady" друзьям в соцсетях.