She smoothed the coat on his shoulder, where there were admirable muscles. She could indulge herself also in stroking his cheek. That was even better—the touch of skin upon skin. “Do you know, when I am with you I am not afraid at all. It is a magic altogether curious that happens inside the heart. I wish I could take it with me when I leave.”

She should not waste her time sitting and talking to him. They both had numerous tasks to accomplish before dawn. But she had not engaged in so many dissipations in her life, after all. She could allow herself a few minutes. “I am frightened of this next journey. The noise of the sea makes it hard to hear what is around me. I must go a long way through this desolation, which is chaotic and full of men trying to kill me. I would avoid it, if I could. I am not an idiot.”

“Think. Just stop and think. If by some miracle you get to England, you’re going to fall into my hands anyway. You’re just delaying the inevitable.” He was working very hard to get free, but she was no amateur at the craft of tying people. “I’m not going to hurt you. I swear it.”

“It is sad, my Grey. We are constrained by the rules of this Game we play. There is not one little place under those rules for me to be with you happily. Or apart happily, which is what makes it so unfair.” She sat more comfortably, pulling her knees up, resting her arms across them. “I have discovered a curious fact about myself. An hour ago I was sure you were dead, and it hurt very much. Now you are alive, and it is only that I must leave you, and I find that even more painful. That is not at all logical.”

In all the time she had known Grey—well, it was not so very long after all—she had never searched his face with her hands to know what he looked like. She could do it now. His hair was short, but soft to hold between her fingers. He had strongly marked bones in his nose—it had been broken once, she thought—and skin of an uncivilized roughness. The ridge of his eyebrows was most pronounced. Not pretty, Monsieur Grey. She had not thought he would be.

“I shall leave you the knife of Henri,” she said, “though I could use it myself. It is in apology for those bumps I have given you with this useful small cosh of mine. You must cut your way free when I am gone. I shall gift you also with Henri, who, I must tell you, I am beginning to find boring in the extreme in his attentions. I have still not murdered him, as you see. I am all benevolence.”

“You’re going to get yourself killed out there.”

“It is very possible.” She had one last minute to stroke his body, to hold on to the warmth of him. He was strong and worthy of respect, and gentle, and her enemy. Her choice of him seemed as inevitable as tides in the ocean. One drowns in the ocean. “Do you know the Symposium, Grey?” She set her palm against the stubble on his cheek. Men were not like women at all, to the touch. “The Symposium of Plato.”

“I’ll find you, wherever you go. You know that. I’ll never give up.”

“You will not find me. You shall not know at all where to look for me. Pay attention. Plato says that lovers are like two parts of an egg that fit together perfectly. Each half is made for the other, the single match to it. We are incomplete alone. Together, we are whole. All men are seeking that other half of themselves. Do you remember?”

“This isn’t the goddamned time to talk about Plato.”

That made her smile. “I think you are the other half of me. It was a great mix-up in heaven. A scandal. For you there was meant to be a pretty English schoolgirl in the city of Bath and for me some fine Italian pastry cook in Palermo. But the cradles were switched somehow, and it all ended up like this…of an impossibility beyond words.”

“Annique…”

Swiftly, softly, she leaned to him and covered his mouth and kissed him. It seemed to surprise him.

“I wish I had never met you,” she whispered. “And in all my life I will not forget lying beside you, body to body, and wanting you.”

“For God’s sake…”

She stood up and jammed the knife in a crack between two stones some distance away, where it would take him a while to get to it. “Adrian was right. I should have made love to you when I had the chance.”

She walked out of the chapel, ignoring his words behind her, which were angry in the extreme, and taking care not to trip on the bits and pieces of her trap that were strewn around the entryway.

Henri’s horse was glad to see her. It did not like being so enclosed by briars. There was less trouble than she would have thought to mount, and no one in this dead monastery would see that her dress was hiked up far beyond decency. She gave the horse its head to find a way out of the courtyard and onto the road. Then all she could do was point toward the sound of the sea, hold on to rein and mane very tightly, and kick hard. It would be dawn soon. There was enough light for a horse to see. At the water’s edge she could follow the line of surf north.

She had come a mile when the road straightened and sloped downward. Henri’s horse picked up speed.

A blow slammed her. Shock. Pain. Falling. She had an instant to know it was a tree branch, hanging over the road, that had hit her. That the horse had done this on purpose.

She fell. Cried out in fear. Her head hit the ground, and the world exploded.

Then, nothing.

The horse, having demonstrated the vicious streak that allowed Henri to buy him cheaply, gave a satisfied grunt and trotted off in the direction of St.-Pierre-le-Proche. Annique lay in a ditch by the side of the road, her face upturned into the drizzle.

SHE hurt. Tendrils of pain reached into the nothing and gave it shape and form. She was pulled unwillingly to a place where pain knifed into her. Her head, in particular, hurt.

It is better to be unconscious. That was her first thought.

Pain filled her head like fire. Like fire. Like…

That was her second thought. Between one instant and the next, she knew.

Light. Light diffused through her closed eyelids. In terror and awe, she opened her eyes and saw pale dawn in the sky. Light everywhere. Light across a whole mass of swirling clouds.

So it had happened. The doctor in Marseilles, with his unnecessary Latin, was right. The horrible bit of something in her skull had shifted off her optic nerve and was now wandering about, preparing to kill her.

She lay, getting ready to die, as the doctor had said she would.

It was entirely typical she should have a view of stubby pine trees to look at for her last minutes of life. Typical she should be stretched flat in soggy, cold mud. She tried to compose her mind to a nobility suitable for such a serious moment. What she thought upon, however, was her stupidity in trusting Henri’s horse and how uncomfortable she was and how hungry her belly felt and how radiant were those tiny drops that quivered down the needles of the pines…the drops that slid along the pine needles and fell one by one onto her face.

She waited. Minutes passed. Nothing happened, except that she became more wet.

It came to her that she was not going to die. Or at least, not just immediately. She sat up. In ordinary times, the ache in her skull would have occupied her attention to the exclusion of all else.

“But this is bizarre.” She found herself looking down at her hands, so automatically did her eyes go to where she’d rested them when she was blind. Amazing to see her own hands again. To see this dress she wore—pale green, smudged with dirt. To see…

She could see. She was no longer the blind, ridiculous worm. She was herself. She was Annique, the Fox Cub. Spy extraordinaire. “I can…see.” She felt hollow with amazement, a shell containing only joy. “I can do anything.” She scrambled to her feet. She wanted to dance. To fly.

The ditch was full of pinecones, which had been uncomfortable to lie among. She found five of them, tightly curled, heavy, and palm-sized.

One. Two. Three. She tossed the simple circle she’d learned from Shandor, when she was eight…that first night she’d come to the Rom and been so lonely.

Catching was easy as breathing. The Two and Two. The Half Shower. The Fountain. So beautiful. She craned her neck far back, swaying to keep under her catches. Her head ached like blazes, but it did not matter in the least.

Bon Dieu, but she was stiff. There had been a time she could sometimes juggle five. Today she was happy to keep a circle of four in the simplest of patterns, a child’s juggling.

She wanted…oh, how she wanted Grey at this moment. She wanted to show him this. Her juggling. Her little art. The trick she had mastered only for the joy of it.

The pinecones were bright and happy in her hands. Nothing lost after all these empty months. Hands and eyes working together. The wonderful eyes that could see for her.

Grey would never see her juggle. Never.

She became clumsy suddenly and missed a cone, so she let the others go. They landed, left and right, hitting neatly on each other, as juggled things do.

She set her face against the tree trunk. It was the same tree that had knocked her into the ditch. In the thick, muzzy silence of the wood, her breath caught in her throat and tears slipped from her eyes. She cried, sad and unspeakably happy.

Sixteen

THE HOVEL FRONTED THE BEACH. AN OVERTURNED fishing boat flanked its door. Leblanc ignored the sobs that came through the wood shutters from inside, ignored also the girl child, held between two burly dragoons, snarling and fighting. His attention was all for the man kneeling at his feet.

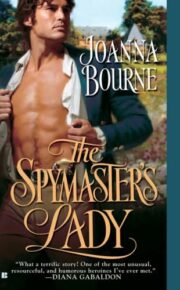

"The Spymaster’s Lady" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady" друзьям в соцсетях.