The coach rolled away, speeding up. The sound of wheels was eaten by the trees.

“Your shoulder?” She made the smallest whisper. Had he torn his wound open?

“Good.” The words fell into her ear almost without sound.

She pressed close to the ground and lay her face into the dirt so the white of her flesh would not give them away. Adrian had also lived through battles. She heard him breathing beside her, face down, hidden.

Silence. Then the jingling of harness and the beat of hooves rose in the distance. Came closer. She could disentangle the sound of six horses, trotting one by one, in a line. After a space, three more followed. She held her breath, pretending to be soil, pretending to be rocks and bushes, until they passed.

When they were gone, she pressed her ear to the ground and waited till even the faintest thud of hooves had faded. Then she waited longer. The hum of insects returned, and the birds singing among the scrubby branches of the pine woods, and she still waited. She wished Adrian had chosen a place less inhabited by sharp sticks. And little bugs.

Nine men. Even Grey could not overcome so very many. He was going to meet his death in these cold woods.

She set her forehead against the cold earth and squeezed her eyes shut tight, for she was crying. It was over, this incident in her journey, and this man, who had torn the heart from her body. She would not meet him again or struggle with the feelings he aroused in her. She knew what Grey had said with that kiss. What he said was farewell.

The mist condensed into a cold drizzle. There was nothing to be gained by staying where she was. She had Adrian to care for, sick and weak, and as much a fool as most men, for all he was very deadly. If she did not stay with him, he would probably die. She said, “It is time to move. I am cold.”

“Me, too.”

“Can you walk? No, give me that. Are you bleeding?”

“Not much.”

She touched his shirt. He told the truth. “Which way? Can you walk?”

“I can walk as far as I have to.”

She took the bag from him. It was heavy enough to contain half a dozen weapons and no doubt did. These English went about armed to the teeth. Adrian put his arm across her shoulder to guide her around the many ruts and to steady himself. It was smoother going when they left the road and entered the old courtyard of the monastery. Their coming disturbed birds and sent them upward in a flurry of wings. That would be uncomfortable for these small birds in this rain.

“The chapel still has a roof on it. We’ll go there,” Adrian said. “Straight ahead.”

The odor of fire clung to this place. Perhaps the Revolutionaries had burned the monks out a decade ago. Or the monastery might have been destroyed in the War of the Vendée, by one side or the other. Once the soldiers were gone, it was not easy to tell which side had burned what.

But no one had bothered to torch the chapel. She pushed the door open and heard the echoes of an enclosure within, with no rain falling. The windows must be broken, though, from the draft of cold air that blew in her face. When she walked forward, her feet kicked aside rubble, dry pieces of wood that had probably been chairs and carved statues. That would make tinder to start the fire.

“There’s shelter at the back,” Adrian said.

There was a space between the altar and the wall of the church where the wind did not reach. She left him there, sitting on the stones, wrapped in his coat. He had no strength to waste, so she did not argue when he told her he would do this thing or that. She just ignored him and did them herself.

It was not easy in her darkness to do those things needed to make a camp, but it was not impossible, either. In her youth, she had pitched camps in many uncomfortable places. The rubble on the chapel floor yielded stones for a cosh and the long stick she needed. Outside was a huge, wet tangle, thorny as a jungle, where the monks once had a garden. On the paths still paved she made her way between the burned timbers and fallen walls. There was bracken in the corners, dry enough to bring in to sleep upon, and enough charred wood to make a dozen bonfires. She even located an apple tree. No blackberries though. The birds must have eaten them all.

There was not the faintest suspicion of fighting in the distance. Whatever had become of Grey, it had been done silently or very far away. She indulged herself, crying as she worked in the rain in this empty garden.

In the end, she dried her face upon her sleeve and finished the tasks she must do, carrying firewood and bracken. She was muddy and very wet by the time she finished, but at least it did not rain inside the chapel. She knelt against the altar, which was marble from the soapy feel of it, and set the small cosh she had prepared next to her knee. She would make a fire. Even before she was blind, she had learned to make fire in the dark.

“It is melancholy, this. I do not have an English spy’s liking for such places.” Wood shavings caught fire in the shelter of the curve of her hand. She fed in tinder—dry scraps that might have been some carved angel, ages old. Someone had stomped it to small pieces, none longer than a finger, but she could make out the shape of wings.

She lay the angel bit by bit into the fire, feeling the delicate, dry lightness, the old paint and gilding upon the surface. “Do they have any chance at all, do you think?”

Adrian sat on the piled bracken, his back to the wall. “They’re very wily. Very experienced. I don’t think the man breathes who can find that pair in this weather in wild country. Grey’s half deer when he’s in the woods.”

“The rain is lucky for us, then.” She balanced slender shards of the wood onto the fire, not burning herself. There is a trick to it, which she well knew. “I can hear the sea outside, if I listen carefully. It is a mile from here, no more. There, that has our fire going nicely.”

“I could do all that.”

“Of a certainty. But my hands like to be busy. I shall set a trap for rabbits in a while. I smell them back there in the old garden.”

“Leave it, unless you’re starving. You’re already wet clean through. There’s a cloak in that bag, one of mine that I brought for you. It’ll keep you warm tonight.”

“It shall keep us both warm. With this fire, I shall be dry soon. Where is that bag of yours? I shall have a look at that, if you please.”

“There’s a loaded pistol on top.”

“Even if I could not smell it I would know there would be a loaded pistol on top of any bag you carried.”

The bracken rustled at her.

“It is not being a spy that makes you so stupid,” she told him. “It is being a man. Now me, I have been playing what you English call the Game for…oh, a dozen years perhaps. Ah. The catch works thusly. I see.” She set the bag open. “In all those years, I have had a loaded gun in my hands precisely three times. And to make it three I must count this. I shall give this silly gun to you, to hide under your pillow.”

“You may put it down very gently right there.”

“You do not trust me with it only because my eyes do not work, though I am unspeakably clever.” She shook her head. “Alas. There is any amount of human folly, do you not think? So this is the cloak you speak of. But it is very nice. It shall go on top of us. You shall put your coat underneath, and we shall have less of this admirable vegetable poking at us.”

“You’re a remarkable woman, Fox Cub.”

“I am, although you do not yet know it, because you have never tasted one of my omelets. Mon Dieu, but you carry many useful things with you. And knives. It is a good knife, this.”

“I like it.”

She touched her way through the last things in the bag. There was a coil of fine-woven silk rope, thin, but strong enough to hold a man’s weight. It was light and smooth as flowing water, and there were yards and yards of it. “Adrian, I will tell you…we are much alike, we two.” She ran the rope reverently through her fingers. “Even though you carry that noisy pistol with the powder that is certainly wet already. This rope…I shall set such a snare with this. You shall help me.”

“Rabbits, Annique?”

She laughed. “But no. Weasels.”

Fifteen

THE FIRE HAD BURNED DOWN TO EMBERS. THE wall of the chapel protected her back, and she held Adrian close to her to keep warmth between them. One cloak, like a blanket, spread over them both.

“There are pictures on the walls,” Adrian said. “I’ve been lying here looking at them. Where the plaster’s left, it’s painted with…I guess you’d call it a meadow. Flowers all over. Thirty or forty different kinds. The columns have vines of blue flowers running right up ’em.”

“It sounds pretty.”

“It is. Right above us on the ceiling, there’s a white bird with the sun behind it. That’s up there getting smoky from the fire.”

“I think we have been sacrilegious. I did not remember this was a house of God when I was roasting apples.”

“The gods moved out of here a long time ago.” Adrian hesitated. “You can’t see what happened here. Believe me, cooking apples is nothing compared to what was done in this place.”

“Do not tell me, then. I have seen enough elsewhere that I can imagine it.”

“We both have.” He moved restlessly, with a crackling in the bedding beneath them. “I wish you’d go to sleep. Unless you’ve decided to pull all these damp clothes off and make wild, passionate love.”

“No, Adrian.”

“I was afraid not. Be a good girl, then, and try to sleep. It’s not your watch. It’s too soon to expect them back. Much too soon.”

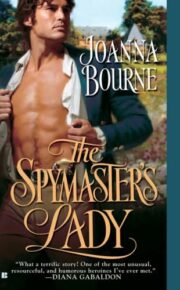

"The Spymaster’s Lady" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady" друзьям в соцсетях.