She’d spent a lifetime dealing with the unexpected. She gripped the reins as if they were ropes to a ship and she was in water in mid-Atlantic. “Nom de Dieu.”

“You don’t want to go choking up on the reins like that. Makes them horses nervous. What you wants to do is hold them bits of leather nice and loose like. Should really be in one hand, o’ course, but let’s us start out with the both of ’em, just at first. What you do…” He put his arm around her, taking both her hands. “No, loosen your fingers up there, and let me show you. What you do is…This gets threaded through here, see.”

“Would you take these back? Please.”

He shifted the straps in her hands till they intertwined with her fingers. “This one over here,” he twitched it in her grip, “goes to the left. That there’s a bad-tempered devil on the left. Nancy, I calls him, on account of him not being what you might call complete in his privates. Old Nan’s a great one for nipping at you when he wants yer attention. Now, suppose you was wanting to turn him to the left—not saying you does now, but if you was wishful to—you’d just pull nice and firm on this strap here. You feel that?”

“Doyle.” She kept a firm hold on the abject terror the thought of these horses running away roused inside her. “It has possibly escaped your notice, but I am blind as a rock.”

“Yes, miss. This other line here, the one you gots lying across your palm like—”

“Being blind, Monsieur Doyle, is not merely a lack of appreciation for the delightful blue sky and the field we are passing. It means I cannot do some practical small tasks. Like drive horses. This is a fact most self-evident that I tell you.”

“Lord love you, miss, you don’t have to see to hold on to these reins. Why, half the time I’m driving along with me eyes closed, just napping. The horses does all the work. The tricky part is remembering which of them lines is which, just in case somebody should climb up and ask you about it.”

She clutched the pieces of leather till her fingers ached. This was not the small, creaky wagon of the Rom and a single, placid Rom horse, which was the only thing she had ever driven in her life. “I most extremely do not think this is a good idea.”

“Best way for you to get around, miss. Driving. If you don’t mind me advising you. Nothing like a pony cart for tooling around the country and no reason you shouldn’t drive as well as any of them ladies in England. Why, from what I’ve seen, a full half of ’em driving must be as blind as you are, begging your pardon for bringing it up and all.”

“You are a man of the most remarkable cold blood, Monsieur Doyle. Mon Dieu, but your reputation is fully deserved.”

“An’ what would a nice young lady like you know about my reputation? When you gets to England, you just go out and get yerself a little cart, a pony cart, and you finds a pony with some sense to him, like this pair has. He’ll take you round as pretty as you please without you do more than set your hands around the reins just like yer doing there.”

“Get…a cart. A cart. But yes, I shall certainly do that if I ever go to England.”

“Now, miss, don’t go on like that. You knows we’re taking you to England with us. Going there just as fast as can be. Getting closer with every mile.” He shifted the straps lightly in her hands, steering the horses past some object in the road. “The sooner you stop fighting Grey about that, the easier it’ll be on all of us. Makin’ us all mortal edgy, you are, not knowin’ if you’re going to kill him tonight or not.”

“Yes. Or no. Whichever it is.” His arms were around her in a friendly way, but he’d let go of the reins again and left her with the whole carriage and these horses who might at any minute do anything at all. “Would you take these lines back, Doyle? Because I, of a certainty, do not want them.”

“You just ease up on the reins a little, the horses’ll walk right along and take us with ’em just fine. Holding on tight just distracts ’em.”

“Lean back and go along most nicely, is your suggestion. Doubtless I am to do the same with all that Monsieur Grey intends for me. It is a very masculine way to advise me.”

“Exactly, miss. And while these horses is walking so nice in the direction of the coast, what you gots to do, if you’ll pardon me saying so, is learn Hinglish.”

“Hinglish?” The meaning penetrated. “Oh. Anglais. But no. I do not just immediately plan to go to England, as it happens.”

“Well, miss, that’s just where you’re going, if you’ll forgive the contradiction. So we’ll teach you Hinglish. Ain’t hard. Me youngest girl—she’s just three—speaks it a fair treat.”

It was easier staying on the box with Doyle’s arm around her. It was even easier when he took the reins and held them, a little way above where her hands were, “Jest to show you how it’s done, miss,” and she could stop being terrified witless.

“Now take them.” He must have made some gesture and realized an instant later she couldn’t see it. “Them horses. In Hinglish we say, ‘Them ’osses is slugs.’”

“Them is…But that is a terrible thing to call horses. Unless the English are fond of slugs, which is possible.”

“Nah. Them’s the buggers gets in the lettuce and crawls all over and eats it. Me wife, Maggie—I tell you about me Maggie yet?—she’s a little spitfire, she is, and mortal proud o’ that garden of ours. Me Maggie ’ates slugs. Sets out saucers of beer to lure ’em in and lets ’em die happy like. Goes against the grain, somehow, drownin’ ’em in good beer.”

She waited for her lips to stop twitching. Her mother had told her Doyle graduated from Cambridge. With honors. “I would agree, though I have never killed slugs. It is still a very strange thing to call horses.”

She was learning that a better class of ‘osses’ were ‘rum prads’ and the Hinglish word for coach was ‘bangup rattler,’ when he took the reins from her and pulled to a halt.

The tenseness of her body must have shown how afraid she was. Doyle said at once, “Nothing to be worried about, miss. Jest looking for a place to stop for a bit. Might be here.”

She felt a sense of humid openness and heard wind and the sound of a stream and humming flies. Birds sang in the distance. They were in the middle of fields then, away from any village, and there was a woods not far. They would operate upon the poor Adrian in the country where his outcries could not be heard.

“This is a good place?” The door of the coach swung open. She heard Grey jump to the ground and walk along the road.

“Might be.” Doyle’s voice was accompanied by a noise that puzzled her, till she identified it as someone scratching an unshaven chin. “What we got here…There’s a couple or three rocks by the road, piled up casual like. That might be Gypsy work. We been following one of their trails a ways now—them scraps of cloth they tie in the trees up about level with a wagon top. So this rock likely means one of their campsites. Maybe back there in that bit o’ woods.”

They were both waiting for her to speak. The British spies, one and all of them, knew a great deal more about her than she liked. “What do they look like, Monsieur Doyle, these rocks of yours?”

“One great lump of a fellow, sorta roundish. That’s in the middle. Then there’s three in a line, running…Lemme show you.” He tucked the reins somewhere and took her left hand and spread it back against his knee and made dots on her palm, showing her how the rocks sat, each with the other. “And then a flat one off here past your little finger, oh, a good foot or so to the right. Don’t know whether that one’s in the flock, or just a stray. Ain’t no twigs or feathers or twists o’ grass anyplace. Just the stones.”

“You have read such signs before.” They had found a Rom campsite, beyond doubt.

“The patrin? Seen ’em here and there, miss. Can’t say I read ’em.”

“Wagon tracks,” Grey called from the fields to their right. “They’re one in the other, dead center in line. Gypsy.”

If Rom were encamped here, they would help her. They would not want to become involved in a quarrel of the gaje but neither would they like to see a woman who spoke Romany in the clutches of such men as these. If she lied ever so small an amount…

Doyle cleared his throat. “They’re not here. Them threads o’ cloth been there a while. Months. An’ the wheel tracks is old. We got the place to ourselves.”

They saw too much, these two. She would have much preferred to deal with fools. “You are right about the patrin, the signs. There is a camp not far from here. A safe place. It will be higher on that stream we passed, higher than the road, so the water flows clean. The Rom are careful in this.”

After a little discussion of the countryside, she directed the coach, not to a closest patch of wood which beguiled them, but up a long track that led into thickets and seemed to them less promising. She knew at once when they reached the clearing that was the Rom’s safe haven. The smell of old campfires hung in the air. The herbs crushed under the coach wheels were the ones the Rom leave behind in their favored camps. Wild garlic, fennel, and mint grew here.

“It’s a good place you’ve found us.” Grey swung her down from her high place on the coach. “This is what we need. You have Gypsy blood in you, Annique?”

“Not from my mother’s side, I am almost sure.” She could smell his shirt, the starch and the vetiver-scented water that was ironed into it, which was wholly a French custom and not a British scent at all. They had such meticulous technique, these agents. “I do not know enough about my father to say—he died when I was four—but I think he was Basque. He spoke with my mother sometimes in a language I have never heard anywhere else.”

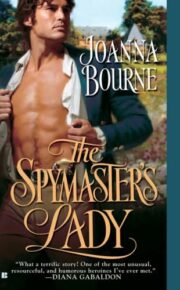

"The Spymaster’s Lady" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spymaster’s Lady" друзьям в соцсетях.