Improvident Harry! He had brought a heavy gold chain for his Juana, and a dressing-case, fit, Anna declared, for a duchess! He had a cartload of Spanish books for her, too, from Havana; and West had got a couple of the little curly white dogs they bred there, and had brought them home especially for Missus! ‘Not much in my line,’ said Harry indulgently. He had much to tell about his last weeks in America: how he had been sent to demand the surrender of Fort Bowyer; how the army, pending the ratification of peace, had been disembarked on Isle Dauphine, at the entrance of Mobile Bay, and what difficulties they had had there in getting fresh provisions; how they could bake no bread, for want of ovens, until Harry, with Admiral Malcolm’s ready help, had made mortar for ovens by burning oyster shells, and had surprised the Generals by producing a column of hot loaves and rolls for breakfast; how West had run into Harry’s tent one morning, and had exclaimed: ‘Oh, sir, thank the Lord you’re alive! A navigator has been going round and round your tent all night! Here’s a regular road about it!’ He had meant an alligator, of course: there were a great many on the island; the soldiers used to eat the young ones, which tasted rather like coarsely-fed pork. The sandflies had been appalling; Harry, who hated tobacco, had given his orderly as much as he could smoke, and had bade him sit under the table in his tent, while he wrote his reports. ‘If you please, sir,’ had said the orderly, a Peninsular veteran, poking his head out with a very knowing look, ‘this is drier work than in front of Salamanca, where water wasn’t to be had, and what’s more, no grog neither! So Harry had sent West for rum and water, and the orderly had said contentedly, ‘Now, your honour, if you can write as long as I can smoke, you’ll write the history of the world, and I’ll kill all the midges.’ When the ratification of the treaty arrived, Lambert, and Harry and Baynes, the ADC, had embarked on the Brazen sloop-of-war, and had sailed for Havana. They were entertained there by a Mr Drake, a wealthy merchant who had married a Spaniard. But all Harry’s spare time had been spent in the Governor’s house, for the Governor had a daughter so like Juana that Harry could hardly tear himself away from her.

‘Yes! You need not tell me that!’ said Juana. ‘You are altogether abominable, mi querido! Muy perfido!’

At Havana, Harry had met Woodville, the cigar manufacturer, a most extraordinary man, who had told Lambert that he had a sight to show which few men could boast of. He had put his fingers in his mouth, and had whistled up forty-one children, of a variety of shades of colour, and not one above thirteen years of age. ‘Report says, Sir John, and I believe it,’ he had told Lambert, ‘that they are every one of them my children.’

‘I thought Stirling and I-Stirling is the Brazen’s captain, you know-would have died of laughing! For dear Sir John, one of the most moral men in the world, said in the mildest way: “A very large family indeed, Mr Woodville.”

Then, in the gulf of Florida, the Brazen had encountered the most terrific gale, and had lain-to for forty-eight hours. At one time, Harry had wondered whether he would ever see his Juana again, but there was never a captain like Stirling, and here he was, after all, never better in his life, and agog to join the army in Belgium.

‘Oh, to be under old Hookey again!’ he said.

‘And me, Enrique? And me?’ Juana demanded, shaking his arm. ‘Of course you, my darling! I told Lambert I should bring you, and he desired his kind compliments, and bade me tell you that he was looking forward to meeting my little Spanish heroine. I did not tell him what a varmint you are, hija!’

‘Oh, Harry, you will not take Juana to Belgium with you?’ cried Mary. ‘Oh, won’t I, by Jupiter!’ said Harry. ‘No more separations for me, I thank you!’

4

It was not many days before Harry heard from Lambert that he was to be employed with the army in Belgium, and that Harry had better be prepared to join him at a few hours’ notice. He would go as Major of Brigade again, a situation which suited him very well. The sisters shed tears, but Juana and Harry danced a fandango, in such wild spirits that sighs and tears were felt to be out of place. The house in St Mary’s Street was transformed suddenly into something very like a military depot; and Anna, seeing tents overhauled, canteens restocked, riding-habits, boots, and boat-cloaks spread out for inspection, was so envious of Juana that she could scarcely bring herself to face her own humdrum future. The most urgent need was for horses. Harry pronounced both Tiny and his own mare too old for further military service, and went off to Newmarket, with Juana and his father, to procure a stud. He bought two good horses there, two more in Whittlesey, and, from his brother Stona, a beautiful mare of his father’s breeding for Juana. They called her The Brass Mare; and a fine, strong creature she was: a perfect lady’s mount-provided that the lady was a perfect rider.

Betsy declared that Harry’s promotion to the rank of Major had quite gone to his head. She said he would very soon be ruined, for besides the batman he would have as soon as he joined the army, he was taking West, a young groom to look after Juana’s horse, and a lady’s maid. How, she demanded, did he mean to transport himself, his wife, his brother Charles, three servants, five horses, and a pug-dog to Ostend?

‘Oh, I shall contrive somehow!’ said Harry carelessly.

Charles, a trifle self-conscious in a brand-new Rifleman’s uniform, was going to accompany Harry. He hoped he would be given a chance to distinguish himself in the coming campaign, because within one hour of putting on his Volunteer-jacket, he had only one ambition: to exchange his shoulder-straps for a pair of Rifle-wings.

Hardly had all the preparations been completed, and the sisters dissuaded from pressing on Juana all manner of comforts which they could as well have carried, said Harry, as the parish Church, than another letter arrived from Sir John Lambert. Sir John was starting for Ghent immediately, and recommended Harry to proceed via Harwich for Ostend to join him. West and Jenkins were sent off at once to Harwich with the horses, Harry arranging to follow with his wife and brother by post-chaise. On their last day at home, he and Juana went riding with John and the sisters, and Harry very nearly put an end to his career by taking a last jump on his old mare. She fell with him, pinning his leg to the ground under her shoulder. For one dreadful minute, the rest of the party expected to see Harry either dead or crippled. No such thing! He was not hurt, and as soon as he found he could not drag his leg out, he passed his hand down till he got a short hold of the curb-rein, gave the mare such a snatch that she made a convulsive effort to rise, and he was able to draw his leg out. He staggered up, bruised, shaken, and faint, but with no bones broken. ‘Good God!’ he said, with an unsteady laugh, ‘there was nearly an end to my Brigade-Majorship that time!’

He was not a penny the worse for the accident next morning; he did not even seem to be very stiff, which was the least, his father said, he deserved to be. At three in the morning, the post-chaise was at the door, and all the misery of parting had to be faced. Poor John, sending three of his sons to the war, was dreadfully upset. ‘Napoleon and Wellington will meet; there will be a battle of a kind never heard of before. I shall not see you all again,’ he said mournfully. All the sisters showed red eyes, and clutched damp handkerchiefs. Juana was kissed again and again; Harry was bidden to take the greatest care of her; a basket of refreshments for the journey was handed into the chaise; Matty, Juana’s country-bred maid, climbed in after it, clutching an armful of cloaks and parcels; and at last they were off. They reached Harwich in the afternoon, and went at once to the Black Bull, where Harry had stayed years before when he had embarked with Moore for Gothenburg. Mr Briton, the landlord, remembered him at once, but said rather dampingly that unless he freighted a craft he had no chance of embarking from Harwich. Every packet was full to overflowing, every ship of any tonnage at all had been commandeered by the Government for the transport of troops.

Charles was much cast-down by this intelligence, but Harry, always at his energetic best when there were difficulties to be overcome, at once set about finding a suitable craft. He got wind of a sloop of a few tons’ burden, and next day, after long and noisy bargaining, came to terms with the skipper, who, with one boy, formed the entire crew of the vessel. Careful measurement satisfied Harry that there would be just room enough for the horses with a little hole left over, aft, for himself, his wife, and his brother to crowd into. Charles, inspecting the ship in dismay, blurted out: ‘This will never do for Jenny!’ ‘Not do for me?’ said Juana, coming out of the tiny cabin on to the deck. ‘Why not?’ ‘It’s so dingy! There is no room for a lady!’

‘Basta! I am not a lady, but, on the contrary, a good soldier. When do we sail on this dear little boat, Enrique?’

That was the trouble: they could not sail until the wind was fair, on account of the horses, and, by ill-luck, a spell of foul weather had set in.

It kept them kicking their heels in Harwich for a fortnight, but at last it wore itself out, the horses and all the baggage were got aboard, and they set sail on an afternoon of sunshine. A gentle breeze carried them over to Ostend in twenty-four hours. They had to land the horses there by slinging them, and lowering them into the sea to swim ashore. When the Brass Mare was in the slings, she saw the land, and neighed loudly, an omen of success, Juana declared.

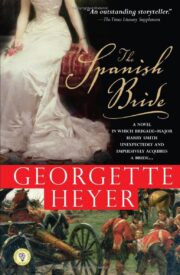

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.