As for the brothers, they used to sit and watch her shyly, quite fascinated by her quick little movements, and her pretty, broken English. Grave Samuel, who was going to be a surgeon, like his father, said in his slow way that his new sister was just like a boy; but Charlie, living with his Uncle Davie, but spending a large part of his time at home, laughed such a notion to scorn. She was not in the least like a boy, he said. She was like-well, he didn’t quite know what, but he thought Harry the luckiest devil going. Charles was plaguing the life out of his father to let him join the army as a volunteer; William, the staidest of the brothers, said it was a piece of nonsense, and he would do better to attend to his books.

There were so many aunts and uncles and cousins living in Whittlesey that Juana was quite bewildered at first. They used to call in St Mary’s Street, on the slimmest of pretexts, Grounds and Moores, and sit looking at Harry’s Spanish wife as though she were a strange animal on show. ‘You must not mind them, Jenny dear,’ Eleanor said. ‘You see, they have never seen a Spanish lady before.’

Mary offered to help Juana with her studies of the English tongue, but the brothers cried out against it. Why, she would not be half as jolly if she did not set them all laughing at the funny words she used, or break into a flood of swift, fierce Spanish when they teased her more than she liked. ‘Whew! What a spitfire!’ Charlie said admiringly, the first time she rounded on him.

‘I must say,’ Betsy conceded handsomely, ‘one would never have supposed Jenny had not been used to living in a large family!’

‘No,’ agreed Eleanor. ‘Does it not bring home to one shocking ignorance of other lands and peoples? I am sure I shall never again be prejudiced against foreigners. Why, only think how we feared she would be stiff and prim, and always wanting to have a duenna with her!’ ‘The most remarkable thing about her,’ said Mary gravely, ’is that she should have gone through such adventures with dear Harry without losing the delicacy of mind which I must hold to be a female’s chief attribute. I own, I had dreaded to detect a certain degree of impropriety; for, you know, to be obliged to live amongst soldiers for so long is enough to blunt the keenest sensibility. The very thought of all the evils of such a situation quite makes one shudder.’

‘Oh, does it, though!’ cried Anna, distressingly tomboy-ish still. ‘Wouldn’t I just love to follow the drum, and have a Spanish horse to follow me like a dog, and eat acorns, and all the rest of it!”

If anything had been needed to win John Smith’s heart, it would have been supplied by Juana’s handling of Tiny. The little horse had been so unmanageable, even with John, who, Harry said, was the finest horseman he knew, that when Juana led him out of his stall, and loosed him, poor John was quite alarmed, expecting him to bolt into his cherished flower-garden. But Tiny minced delicately behind Juana, with Vitty trotting beside him, right up the neat path, and into the drawing-room. The Smiths could hardly believe their eyes. Then of course nothing would do for Harry but to make his wife change into her habit, and show off herself and the horse, figuring him as well as any Mameluke. Harry was allowed just three weeks at home before letters reached him from the Horse Guards. The first he opened ordered his immediate return to London; the second drew from him a shocked groan that brought Juana quickly to his side.

‘Ross!’ he said. ‘Oh, the fool, the dear, kind fool! I might have known it!’ ‘John Ross?’ she cried. ‘Oh, what?’

‘No, no! Poor General Ross! He let them persuade him-De Lacy Evans and those damned Admirals!-and attempted Baltimore on the 12th September, failed, of course, and lost his life there! Good God, he was dead when we were congratulating his poor wife on his success at Washington! It does not bear thinking about!’

Juana’s eyes were fixed on his face. ‘And that other letter?’

‘I am to return instantly to London. Pakenham is appointed to succeed Ross, and I go with him as AAG.’

Nothing could soften such a blow, not all the caresses of her new family. Juana’s white face brought tears of sympathy to the sisters’ eyes. Everyone tried to be helpful, and so many people assisted in packing Harry’s portmanteau that it was wonderful that it was ever induced to shut. Aunts and cousins brought all manner of unsuitable comforts for an officer about to set out in the middle of the winter to cross the Atlantic; and Grandmama at the last moment tried to fit in a jar of her own apricot preserve.

There was no question this time of Juana’s living alone in London. John Smith was going to take her up to see the last of Harry, and bring her back to Whittlesey when he had gone. They all three of them went to Panton Square, and, fortunately for Juana, time was so short, and the things to be done so many, that there was no opportunity for indulging in melancholy reflection.

Harry went at once to see Pakenham, who greeted him most warmly, and told him that they must sail in a few days from Portsmouth, on the Statira frigate. Harry knew Pakenham of old, and already entertained a great respect for his talents. His reputation in the army was high, for whether he was leading another man’s division in a spectacular charge, as at Salamanca, or performing the duties of Adjutant-General, as he had done after Vittoria, he was always cool, competent, and unfailingly light-hearted.

To Harry’s delight, he found that the 3rd battalion of the Rifles was destined for America, and that his old friend, John Robb, of the 95th, had been appointed Inspector-General of Hospitals. He and Robb arranged to travel down to Portsmouth together, sending West ahead with then-baggage; and at three o’clock on a grey November Sunday, Harry once more said farewell to his wife.

For him at least it was not so painful a separation as at Bordeaux, for he had the comfort of knowing that he left her in his father’s tender care; but for her it meant more months of anxiety, more searching of the newspapers for dread tidings from America. She behaved with great courage, trying hard to show a smiling face at the last, but he left her, half-fainting, leaning her forehead against the mantelpiece, and pressing her handkerchief to her lips to force back the sobs that crowded in her breast.

‘Good-bye, my dear boy, good-bye!-You know I will look after her as though she were indeed my own daughter!’ cried John, quite overcome.

‘God bless you!’ Harry said hoarsely, and fairly dashed out of the room.

Chapter Eleven. Waterloo

Back again in Whittlesey, life lost its zest for Juana. She rode with her father-in-law, paid morning calls with Mary, and learned how to make apple-jelly from Betsy; but although she never repined it was sad to see how her buoyancy left her when Harry was not by. Everyone felt his absence, of course. There were seven young persons in the house in St Mary’s Street, but with Harry’s departure quiet seemed to descend upon it, Anna, yawning, said that life was abominably flat, and although Mary reproved her for using such unconventional language, she admitted that it did seem a little dull.

The weather grew very cold. An icy wind cut across the Cambridgeshire flats, howled round the corners of the house at night, and whistled under the doors, lifting all the carpets. Eleanor’s fingers were swollen with chilblains, Mary developed a streaming cold, and Betsy complained that do what she would she could not exclude draughts from the house. Only Juana did not seem to feel the cold. When the sisters pointed out the stupid position of the windows, the disagreeable habit the dining-room fire had of smoking when the wind blew from the north-east, and the impossibility of warming the hall and stairway, she opened her eyes at them in surprise, and said she thought the house muy comodo. They exclaimed, but when she described her winter quarters at Fuentes de Onoro, and the mud hut Major Gilmour had bequeathed to her on the Grande Rhune, they owned that there could be no comparison.

Snow fell from a leaden sky in December. The bleak countryside seemed to shiver under it, and the farmers prophesied a white Christmas.

‘Your first English Christmas, dearest!’ Eleanor said, bringing a prickly armful of holly into the house. ‘If only our dear traveller could be here to share it with us!’ ‘Never mind,’ Juana said. ‘There will be a letter from him soon now.’ She was so sure that Harry would write; the sisters hoped that she would not be disappointed; but they said, sighing, that neither Tom nor Harry were very regular correspondents. ‘He promised me,’ Juana replied, with impressive simplicity. She began to be rather restless about a week before Christmas, because she thought that the Statira must have reached America by then, and perhaps already Pakenham’s force was engaged with the enemy. Her interest in the Christmas preparations was dutiful, but a little perfunctory, and she did not much enjoy the party itself. It was soothing to her present mood to accompany the family to Church in the morning, and to pray for Harry’s safety (for she had not the smallest hesitation in entering a Protestant Church), but the big dinner-party in the evening she found rather overwhelming. There were so many relatives present, all chattering about family affairs, and laughing at old jests, that she felt herself a stranger, and would have slipped away had not John seen the disconsolate look in her face, and moved over to sit beside her, and to talk to her about the subject nearest to both their hearts. In the New Year, John had business in London, and he took Juana and Anna with him, travelling post all the way. There had been heavy snow-falls, and once they came up with a stage-coach which had strayed off the road into the ditch, and lay there with two wheels cocked up in the air.

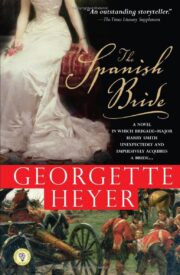

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.