‘Why, damn my eyes if our old Brigade-Major is killed after all!’ one of them exclaimed.

‘Come, pull me out!’ said Harry. ‘I’m not even wounded: only squeezed!’ ‘Lor’, sir, you’re as bloody as a butcher!’ said a stout private, hauling him out from under the mare.

Harry did not trouble to wipe the blood from his face, but ran to join Colborne, who had pulled out his note-book, and was writing in it, in French, I surrender unconditionally. ‘Hallo, Smith! I thought you were dead. Give this to that fellow, and tell him to sign it,’ Colborne said.

The French officer burst out laughing when Harry went into the fort. ‘One would say you were a walking corpse!’ he said. ‘You are literally covered with blood!’

‘Nevertheless, I’m very much alive,’ replied Harry, giving him Colborne’s paper to sign. The officer grimaced at the words Colborne had written, but since there was no help for it, scrawled his name, and gave the paper back to Harry.

‘That’s right,’ said Colborne, when Harry brought it to him. ‘Find yourself a fresh horse, and take it to Wellington.’

‘Here, have mine!’ Fane said, thrusting his bridle into Harry’s hand. ‘What a sight you are to be sure!’

Harry was, indeed, such a mask of blood that when he rode up to Wellington, his lordship demanded: ‘Who are you, sir?’

‘The Brigade-Major, and Rifle brigade, my lord,’ replied Harry. His lordship stared at him. ‘Hallo, Smith! Are you badly wounded?’ ‘Not at all, sir: it’s my horse’s blood,’ said Harry, giving him Colborne’s paper. ‘Well!’ said Wellington, taking it, and running his eye over it. ‘Tell Colborne I approve. Did you lose many men in that affair?’

‘Yes, my lord, very many.’

‘I’m sorry for it,’ said his lordship, looking down his nose. ‘No need to have attacked the redoubt.’

‘Our orders were to move on, sir.’

‘Dey were not mine! Dere is some mistake!’ Alten said angrily. ‘I sent no order to Colborne! I dink Colborne understands his pusiness fery well widout such orders from me.’ ‘Ah-h’m! I wish Staff-officers would learn to know their duties better!’ said his lordship, with one of his frosty glares.

6

By two in the afternoon, Clausel’s troops were retreating across the Nivelle in confusion; at dusk, Wellington crossed the river with two divisions; and the Light, the 4th, and Giron’s Andalusians bivouacked on the reverse slope of the original French position. Here Juana rejoined the brigade, coming up with the baggage early on the following morning, and almost swooning with horror at the sight of Harry’s blood-stained garments. That he was not wounded seemed to her incredible; she could not believe that he was not concealing some dreadful hurt from her. He took her by the shoulders and shook her, saying: ‘Will you have sense, estupida, or must I strip to show you that I have nothing but a few bruises? It was the mare who was hurt, not I!’

She exclaimed at once: ‘I knew it! Did I not tell you what would happen? You are not wounded at all?’

‘No, I tell you!’

Her terrors laid, she suffered an instant reaction. ‘Oh, you are abominable to frighten me so! I won’t speak to you till you have washed yourself, and taken off those horrible clothes!’ ‘As though I had not been longing to take them off all this time!’ said Harry. ‘Won’t you kiss me, my hateful darling?’

‘No! Your face is smeared with blood! I would sooner kiss Ugly Tom!’ she declared. She went off to visit one of his friends, who was wounded. He did not see her again until much later, and then it was she who was in need of a change of clothes, for out of two hundred men of the 52nd regiment returned as killed and wounded, a hundred, suffering from flesh wounds, had refused to go to the rear. Quite a number of these needed attention, and Juana, who had become expert in the washing and binding up of hurts, was busy all the morning. When Harry, very spruce in his best jacket and sash, encountered her, he recoiled, his narrow eyes gleaming with laughter, and said: ‘Oh, you horrid little thing! Don’t touch me!’

‘Oh!’ Juana cried. ‘One little bloodstain! How nice you look! Kiss me quickly, for I must go and wash my hands!”

‘Not till you have washed, and taken off those clothes!’ murmured Harry wickedly. ‘I’m going to find out how many of my friends were hit yesterday!”

‘Well, I can tell you that all our particular friends are safe, only Johnny Kincaid is quite wretched about poor Colonel Barnard, for he fears he will die.’

This was very bad news, and had the effect of sending Harry off immediately to find Kincaid, who was Barnard’s Adjutant. The Colonel had been knocked off his horse by a musket-ball through the lung, and by the time Kincaid had reached him he was so choked by blood that he could not speak. His men gathered round him in the greatest distress, for he was very much beloved, but Kincaid, seeing George Simmons not far off, had the presence of mind to shout to him to come to Barnard quickly. George washed the blood out of Barnard’s mouth, felt the wound, and looked grave, but upon Barnard’s regaining his senses, and saying to him: ‘Simmons, am I mortally wounded?” he had replied in his honest way. ‘Colonel, it is useless to mince the matter: you are dangerously wounded, but not immediately mortally.’

‘Be candid!” Barnard had said. ‘I’m not afraid to die.” ‘I am candid,” George said steadfastly.

Four men had carried the Colonel off on a blanket, George accompanying them. It was expected that George would return to his regiment on the following day, but just before the brigade moved on, Joe Simmons got a message from him that he was staying in Vera for the present, in charge of Barnard, who was going on remarkably well, and had placed himself in George’s sole care.

‘Dear old George, how he must be enjoying himself!’ said Kincaid. The brigade moved on that day, descending into the fertile French plain, and reaching Arbonne. After the wild mountains they had been amongst for so long, the sight of neat farmsteads, and tilled fields, intersected by hedgerows, pleased everyone. Hay was obtainable for the horses, too, which relieved mounted officers of one of their most pressing anxieties. The weather, however, was bad, and it was evident that a great deal of rain had fallen on the plains, since all the ways were spongy with soaked clay. Tiny sank in this sticky mud to his knees, a circumstance which made Harry Smith think poorly of the army’s prospects of continuing the drive into France.

He was quite right. The condition of the ground made the passage of the artillery almost impossible, nor could the heavy cavalry be brought up from their quarters in Spain. Had the weather been clement, and the Spanish troops better fed, there was no saying how far Wellington might not have thrust Soult. He had forced him to evacuate St Jean de Luz, which town he made his own headquarters, but he might have been able to do more. ‘I despair of the Spaniards,’ he wrote to Lord Bathurst, ten days after the battle.’ They are in so miserable a state, that it is really hardly fair to expect that they will refrain from plundering a beautiful country: particularly adverting to the miseries which their own country has suffered from its invaders. If I could now bring forward 20,000 good Spaniards, paid and fed, I should have Bayonne. If I could bring forward 40,000,1 do not know where I should stop. Now I have both the 20,000 and the 40,000 at my command, upon this frontier, but I cannot venture to bring forward any. Without pay and food, they must plunder; and if they plunder, they will ruin us all.’

It was some consolation, while Freire’s and Longa’s men were sacking Ascain, and Mina’s wild guerrilleros were rapidly approaching a state of open mutiny, that his lordship was able to tell Bathurst that the conduct of the British and Portuguese troops was being exactly what he wished; but the atrocious behaviour of the starved Spaniards came at the worst possible moment. Never was the time riper for a bold thrust. ‘Where are your Emperor’s headquarters now?’ Wellington asked one of the French officers, who had been taken prisoner.

‘Nulle part,’ the Frenchman had answered sadly. ‘Il n’y a point de quartier general, et point d’armee.’

It was not every Commander, advancing into enemy territory, who would have been able to bring himself deliberately to dispense with 40,000 men out of his whole force; but Wellington’s cold judgement convinced him that delay in completing his operations would be less harmful to the Allied cause than the depredations of the Spaniards in a country which it was vital to conciliate. Having hanged an astonishing number of the marauders without achieving any improvement in the conduct of the rest, his lordship deliberately sent every Spanish division except Morillo’s back to Spain.

The weather grew worse. The Light division, bivouacking near Arbonne, in hourly expectation of being ordered to advance, was moved forward only as far as the town, and quartered there. It was an uncomfortable situation, for it rained incessantly, and although the French inhabitants of the district were as friendly towards the British as Wellington had been assured they would be, there were bickering fights going on with Soult’s forces, entrenched before Bayonne; and every day seemed to bring skirmishes with outposts all along the line of the front.

As soon as the rain stopped, and the sodden ground was dry enough to make an advance possible, the division was moved forward, nearer to Bayonne, and quartered in two large chateaux. The first brigade was at Arcangues, the second at Castilleur, in which Colborne packed the 52nd regiment, Harry said, as close as cards.

It was December by this time, and they began to think of Christmas. Colborne’s Staff had bought a goose, and if it did not die from surfeit, Colborne said, they would give a grand dinner on Christmas Day.

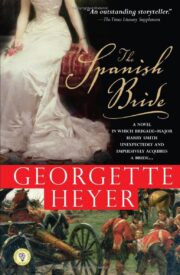

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.