Pampeluna he was content to starve into submission; San Sebastian was a more pressing problem, and was proving as tough a nut to crack as Burgos. Officers, going off to the coast on a day’s leave, reported that it was a bad place to have to take, the town and fortress being perched on a great sandstone rock, jutting up four hundred feet out of the sea, which washed it on three sides. Graham’s force, they said, was welcome to the task of reducing it. But, all the same, when the news reached Vera that the assault by the 5th division had failed, the Light Bobs said that until they were called upon to storm the place it probably never would be taken. A most unjust rumour spread that the Pioneers had not acquitted themselves very creditably. ‘Ah well!’ said the Light Bobs, maddeningly indulgent. The siege was raised on the day after the assault, news having reached Lord Wellington that Hill was engaged at Roncesvalles and at Maya, and had suffered some heavy casualties. Soult had moved at last, and rapidly, attacking the Allied right with the obvious intention of forcing the passes, and striking south to relieve Pampeluna. ‘Be ready to march at a moment’s notice!’ Harry told Juana.

She had barely packed their portmanteau when an orderly brought her a hurried note from him: Stewart had lost the Maya pass, and the Light division was ordered to retire from Vera towards Yanzi, or even to Santesteban.

Off they went, the echo of gun-fire sounding on their left. No one, not even Alten, had any knowledge of the division’s ultimate destination, nor could they obtain any very certain news of the fighting in the hills round Roncesvalles. They passed through Lesaca, finding all the headquarters Staff either packing-up, or already gone, and the whole town choked with pack-horses, and mules, and wagons. From Lesaca, they marched along a flinty road until nightfall, when they encamped on a height near Sumbilla. Rumours were flying about: it was said that D’Erlon was over the pass of Maya with twenty thousand men, everything giving way before him, which made it seem certain that the division was being marched south to join in the defence of Pampeluna.

On the night of the 27th July, the division, marching again, blundered along craggy mountain-paths, with ghastly precipices lurking in the pitch-darkness to swallow up the unwary. Nerves were on the jump; men were heard shouting to one another, their voices sharpened by dread of being lost in this savage wilderness of broken hills, and deep, dangerous water-courses. Faggots were kindled for torches, but the darkness was like a smothering pall. Climbing a goat-track too narrow to allow of three men’s walking abreast, the and brigade was brought to a ragged halt by a yell of terror, and the sickening sound of a body’s rolling and bumping away into the black void beside the path. It was a Rifleman, who had stepped unknowingly over the edge of the track; they could hear the clatter of the canteen on his back as it struck against the rocks, and the rattle of loose shale tumbling down the mountainside. The man who had been plodding along beside him stood shaking as though he had ague, but when the noise of the fall had died away, suddenly, from a long way below, a voice floated up to the soldiers’ straining ears. ‘Hallo, there!’ it shouted, quavering a little, but resolutely jaunty. ‘Tell the Captain there’s not a bit of me alive at all; but the devil a bone have I broken, and, faith, I’m thinking no soldier ever came to his ground at such a rate before! Have a care, boys, you don’t follow! The breach at Badajos was nothing to the bottomless pit I’m in now!’

A burst of relieved laughter greeted this sally; he was retrieved from his pit, but the incident had shaken everyone’s nerve, and progress grew slower than ever, so that when the dawn crept into the sky, the division found that it had covered barely half a league. By the 30th of the month, they had reached Lecumberri, not much more than ten miles from Pampeluna. The sound of heavy cannon-fire to the east rumbled all day long, and even the sharper rattle of musketry could be heard. The knowledge that somewhere in the vicinity a battle was being fought kept the troops marching doggedly on, but although Alten sent out messenger after messenger to try to get news, nothing certain was learned, and no fresh orders reached the division from wherever Wellington had established his headquarters. Harry, his wiry frame not much affected by the heat, the varying altitudes, or the hardness of the march, was, as usual in trying circumstances, a tower of strength. Neither his energy nor his cheerful rallying tongue flagged for a moment, but the lines of his sun-burnt face might have been cut with a chisel, and even when he cracked a jest to encourage an exhausted private his eyes were strained with anxiety.

‘Harry’s learning what it is to worry,’ said Colonel Ross.

‘Poor devil!’ Charlie Eeles muttered. ‘Wonder what he’ll do if she has to fall out?” But Juana was not going to fall out. Not she! Tiny was so sure-footed that no one need concern himself about her, she said. As for the necessity of dismounting, and leading her horse up the steepest and roughest parts of the track, what was there to complain of in that? She assured solicitous inquirers that the broken bone in her foot was quite healed, and caused her no discomfort at all.

‘Nada me duele.’ she said. ‘I think it is much better than our march to Rueda, because we were so thirsty then-ti acordas?-and here there are so many streams.’ ‘My poor little sister, you’re so tired!’ Tom Smith said, finding her leaning against Tiny’s shoulder during a few moments’ halt by one of the streams, and breathing in overdriven gasps.

‘Don’t tell Enrique!’ she managed to say. ‘No, no, but if only I could do something to help you!’ ‘It is nothing. It is only the mountains which make me pant so.’

Whenever Harry came riding down the column to the rear, she straightened her back, and greeted him cheerfully. He never uttered a word of pity; he seemed to take it for granted that she would keep up with the brigade, and spoke to her very much as he would have spoken to a young subaltern who needed encouragement; but between their puckered lids his eyes searched her face for the signs of exhaustion he dreaded, and in the bivouac he would roll her in her blanket as though she had been a baby, and sleep with her head pillowed on his shoulder, and his arms folded close about her.

They reached Lecumberri after dusk, and camped in a wood. It was chilly at night in the mountains, and the men built fires, and lay round them, within walls of pack-saddles, and bulky kit-bags.

‘Muy comodo,’ Juana said sleepily, blinking at the flames. ‘It is nice here, don’t you think, Enrique?’

‘If these damned mountain mists don’t set you fast with rheumatism!’ ‘How foolish! Do you imagine I am like General Vandeleur?’ ‘Not a bit. Kiss me, alma mia di mi corazon!’

3

Not until late in the afternoon on the following day did any orders reach the division from Lord Wellington. Such news as Alten’s scouts brought in was vague, culled from the lips of peasants, and imperfectly understood. There seemed to have been heavy fighting somewhere north of Pampeluna, and there could be no doubt that Soult had made a big thrust through the mountains. Alten’s hatchet-face was as calm as ever, but his Staff found him unusually curt, and when his messengers came back reporting failure to get into touch either with Wellington, or with Hill, a muscle twitched in his cheek, and he folded his lips as though to keep back a hasty word of censure. The troops, although they badly needed their enforced rest, could not enjoy it while rumours of an engagement were in the air, but fretted a little, wanting to know what they were doing, lying up in a wood while the rest of the army was fighting the Johnny Crapauds.

But at dusk, a cocked-hat, white with dust, was seen, and the word ran through the lines that one of the Squire’s ADCs had ridden into the bivouac, more dead than alive, and had fairly tumbled out of his saddle into Quartermaster Surtees’s arms. He brought an order, dated the previous day, from Wellington, and had been hunting for the division until his horse almost foundered, and he himself reeled in the saddle from sheer fatigue. Soult had been defeated at Sorauren, after a very sharp engagement, lasting for two days, and the Light division was to retrace its steps at once to Zubieta.

Some hard swearing was indulged in, from the General down to the newest-joined private, for nothing was hated more than counter-marching. The Staff was blamed, of course, but it was, in fact, nobody’s fault. With the Light division once set in motion through a maze of mountains and twisted valleys, it had been a difficult task to find it, and to halt it; and a running-fight, culminating in a two-day battle on the right wing, had not made matters any easier.

Alten issued his marching-orders immediately, and the division broke camp in the failing daylight. No more than nine miles was covered, for Alten, with the lesson of one night march along mountain roads behind him, halted the division at Leyza, as soon as darkness fell. Fresh orders from headquarters arrived during the small hours. Soult had retired by the Pass of Arraiz, and was making for Vera, and the neighbouring village of Echalar. His lordship desired Alten to head him off, if possible, at Santesteban; failing that, seven miles farther north, at Sumbilla; or at least to cut in upon his column of march somewhere. But his lordship had hoped to find the Light division at Zubieta, within five miles of Santesteban, not ten miles distant, on the other side of a difficult pass.

The division was under arms at dawn, and by noon had reached a point a few miles from Santesteban, after a hard march. ‘George has the best of it after all,’ said Molloy, mopping his brow.

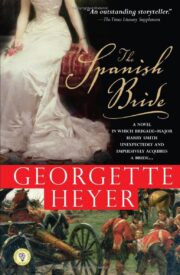

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.