The British officers thought that King Joseph and Marshal Jourdan would make a stand on the fine of the Pisuerga river, but again the French fell back, this time on Burgos. King Joseph, very much in the dark as to his adversary’s intentions, compelled by necessity (and the most stringent orders from his autocratic brother and mentor) to retain the great road to France that ran through Burgos and Vittoria, was nervous of the Pisuerga position, and found it, moreover, impossible to obtain food for his army there.

When it was realized in the Allied ranks that Burgos must be their objective, the prospect of having to engage upon a protracted siege damped everyone’s spirits. The Light Bobs had no doubt that they were destined to be employed on this labour. They would take the town, of course: no question about that; but they looked forward to it with gloomy feelings. Everyone hated siege-work; and everyone would rather fight in half-a-dozen open battles than take part in one storm of a fortified city. By all accounts, Burgos would be as hard a nut to crack as Badajos had been, and no one could think of that hellish business without hoping that he would never again be asked to go through such a hideous night. When, on the 12th June, the line of march took an abrupt turn eastwards, and the troops knew themselves to be marching on Burgos, there was less than the usual amount of cheerful talk in the ranks. Pessimists prophesied a month’s trench-work under gun-fire, and when the division bivouacked that night at Hornilla, there was a faint atmosphere of depression over the camp.

But very early next morning the men were startled by the echoes of a terrific explosion. It was so loud that it brought many to their feet and it was followed at intervals of a minute or two by three more. No one knew what had caused them, although the wildest hopes burned in nearly every breast. It was said that Wellington had ridden off with the various divisional commanders to reconnoitre; he was seen returning a few hours later; and the news that Marshal Jourdan had evacuated Burgos, blowing up the Castle, and was in retreat towards the Ebro, spread quickly through the camp.

Shakos were flung up, and the air made loud with hurrahs. Orders to break camp and march towards the Ebro arrived, and were hailed by renewed cheers. Canteens were packed, fires stamped out, tents loaded on to the mules, and the division marched north-eastward in the best of good spirits.

Chapter Six. Vittoria

The columns, leaving behind them at last the vast Tierra de Campos, with its miles of unbroken cornfields, plunged into a maze of rocks and towering hills; dropped from the mountains into the valley of the Upper Ebro; and thought themselves come suddenly upon the Promised Land. Giant-cork trees gave shade from the sun’s glare; fruit and flowers grew everywhere. From pretty little villages girls trooped out with garlands to throw over the heads of los colorados. They danced before them on the dusty road, and offered great baskets spilling with cherries and pears. The soldiers, disheartened by the waste of rocks amongst which they had forced a difficult way, revived at once; and as they crossed the Ebro the regimental bands struck up The Downfall of Paris.

On they went, hustled forward on long, hard marches for three sweltering days, sometimes panting up mountain-sides, sometimes plodding through the lush green valleys. Very few of them knew where they were going, or where any column other than their own was. There were troops (they were Graham’

s) somewhere to the north, for the dull thunder of artillery-fire rolled and echoed one day round the hilltops. So it looked as though a part of the army was thrusting northward, probably to outflank the French. The Light division, ordered to leave its baggage and artillery with the 4th, branched away from the road skirting the foothills, and crossed the mountains by a track which everyone but Lord Wellington would have thought impractical for troop movements. They had their reward when they dropped down into the village of San Millan, for there they came plump upon a brigade of Maucune’s, resting with piled arms and no pickets posted. As luck would have it, Vandeleur’s brigade was leading, and was the first to launch an attack upon the startled enemy. Harry had not time to do more than shout to Juana to keep back, as he galloped past her to bring the 52nd regiment up to support the Rifle battalion. Vandeleur was deploying swiftly; a cacophony of trumpet-calls blared through the village; and the French, who had seen nothing of the Allied column’s advance along the hollow road, masked as it was by jutting rocks and steep banks, tumbled into some sort of battle-order.

The Riflemen went down the slope at the double, firing as they ran, and yelling: ‘The first in the field and the last out of it, the bloody, Fighting Ninety-fifth!’

Juana had to dismount, and drag her horse out of the way of the men coming up in support. An aide-de-camp went past her in a cloud of dust to hasten the advance of Kempt’s brigade, closely following Vandeleur. The fight before the village rapidly became a confused mêlée, the second French brigade, with the baggage-tram in its rear, suddenly appearing through a cleft in the rocks, and being engaged by Kempt. The sumpter-beasts broke loose and stampeded amongst the rocks; a rough-and-tumble fight bickered all over the slopes of the hills; and the French, ignorant of what troops the hollow road might still be concealing, presently took to their heels, many of them throwing off their kit-bags to make their flight over the rocks easier.

When Juana, who had watched the fray in a state of bouncing excitement, rode down into the village, the dust kicked up by the skirmish was beginning to settle, and the ground was littered with scattered baggage and accoutrements. The whole of the baggage-train had been captured, and about two hundred prisoners. A very good day’s work, was the verdict of the Light Bobs, counting the spoils, with only four dead men and a handful of wounded to offset the victory.

However, when the division halted at Pobes on the following day, and Alten ordered the French baggage to be sold by auction, a spurt of ill-feeling sprang up between the brigades, Kempt’s men, in spite of having captured the train, being allowed no opportunity of bidding for the various goods. Feelings ran rather high for a time, but when it was discovered that the army had at last come up with the main body of the enemy, which was drawn up behind the twisting Zadorra river, on the undulating ground before Vittoria, such trifling considerations were forgotten, and nothing was thought of but the approaching engagement.

Lord Wellington spent the day surveying in person the various routes by which he meant to launch his force on to the French. He was in good spirits, but a little curt with his Staff. Some of these gentlemen had deprecated his rapid march north. They did not consider it safe to go beyond the Ebro, and the magnitude of his lordship’s plans alarmed them. His lordship was unmoved by their disapproval. He had no opinion of King Joseph, not much respect for Marshal Jourdan; and he knew that although Sarrut had joined the King’s army from Biscay, there was still no news of Clausel’s advance. One or two critics said that his success at Salamanca had gone to his head; but they did not realize, as his lordship did, how crushing a blow to French morale that spectacular victory had been. He was, in fact, in a confident mood, though that did not prevent his snapping the heads off his personal Staff, said one of his rueful aides-de-camp, who had asked him a question which his lordship considered unnecessary.

It was misty on the morning of the 21st June. It even rained a little, but the weather prophets thought that the day would fair-up. The Light division was called to arms very early, and on their way up to their station before the. Zadorra river they passed through the sleeping camp of the 4th division. But they were not destined to be the first to attack: that honour had fallen to Hill, and no one else was to be allowed to make the slightest move until it had been seen that he had gained his objective.

Harry knew all about it, of course; he had had a look at the ground too, and he knew that the Intelligence-officers were speaking the truth when they reported that the French were spread over too long a front, and had insufficient guards at the various bridges across the Zadorra. King Joseph was in the uncomfortable position of being quite in the dark about his adversary’s intentions; and although his patrols had been feeling cautiously for the Allied army for some time past, they had brought in only the most confusing reports of the advance. He could get no tidings of Clausel, who, for all he knew, might still be hunting guerrilla-bands in the wilder parts of Biscay; and not only was the town of Vittoria crammed with civilian refugees, who were clinging to the skirts of his army, but amongst all the congestion of carts, caissons, and artillery-wagons were several fourgons from France, inscribed Domaine exterieur de S.M. l’Empereur, containing specie to the value of five million francs. Like Lord Wellington’s, King Joseph’s soldiers had months of pay owing to them. The King had been very glad to see the long-overdue fourgons, but when faced with the imminent prospect of having to fight a battle he could have wished them otherwhere.

The so-called plain of Vittoria, on which, after many heart-burnings, the King had determined to make a stand, was a stretch of rolling ground, about twelve miles long from north-east to south-west, and varying in breadth from six to eight miles. It was surrounded by hills, and drained by the Zadorra, a turbulent stream, affording, from its twisting nature, the very worst of fronts. Some of its bends were so sudden that the river seemed almost to double back on its course. It had several bridges, and, since the stream was easily fordable, these had been left intact. Vittoria, a town where five roads met, was situated some miles behind the Zadorra, on rising ground; and dotted over the land, in wooded valleys, were a number of villages.

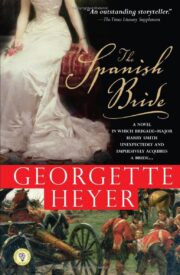

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.