She was perfectly satisfied. Had Lord Wellington himself appeared to inform her that the two divisions were in imminent danger of being cut off from the rest of the army, she would have paid very little heed: Harry had said that they were quite safe.

The truth was that Marshal Marmont had succeeded in foxing his English adversary. Having completed the repairs to the bridge at Toro, he had sent Bonnet’s and Foy’s divisions across the river. Wellington, from the outset jealous of his left wing, began to concentrate his army on the Toro road, only to discover that the wily Marshal had suddenly reversed his marching orders. Bonnet and Foy, recrossing the Douro, formed, instead of the van, the rearguard, and the entire French force countermarched on Tordesillas. Cotton, whose last orders had been to halt the two divisions under his command at Castrejon, reached that village on the 17th June, and drew up his small force into position. The news brought in by the patrols was disquieting. The French were pouring over the Douro at Tordesillas, and by nightfall the bulk of Marmont’s army had reached Nava Del Rey, a bare ten miles north of Castrejon.

Castrejon was situated on the Trabancos river, a small tributary of the Douro, in the middle of bare, rather down-like country. The two divisions lay by their arms all night, by the smouldering camp-fires, with the distant croak of frogs and the intermittent fidgeting of the picketed horses disturbing the night-silence.

A little after sunrise on the morning of the 18th June, a cannonade began. Cotton’s outposts were driven in, and he at once formed his cavalry in front of the two infantry divisions, which were separated one from the other by a wide ravine. A hill, beyond the Trabancos, hid the French army from view, but parties of horsemen could be seen through the wreaths of the ground-fog which lay over the river-valley. Harry found time to send Juana to the rear, for the situation had begun to look a little dangerous, no word of support having as yet come from Lord Wellington. Cotton was cautiously advancing his cavalry into the fog, but although nothing could be seen by the waiting infantry, a sharp outburst of musketry-fire soon gave them to understand that Anson’s horse had encountered more than cavalry in the valley. A regiment of foot passed through Castrejon at the double, moving up to support Anson, as the cannonade intensified.

The river-mist began to curl upwards forming a kind of dome that was shot with iridescent colours by the rising sun. Through the heavier, smoke-laden vapour below, the figures of horsemen seemed to flit restlessly in mazy convolutions. The flashes of muskets flickered incessantly; and as the mist lifted higher the head of land beyond the stream became apparent, and was seen to be thickly covered with French troops.

‘Queer sight,’ remarked James Stewart, in his pleasant, disinterested drawl. ‘Really remarkable!’ He glanced at Harry, who had paused for a moment beside him. ‘I should hate to make a rash pronouncement, but it would appear that we are in a rather tight hole.’ ‘I wonder how long we can hold our ground?’ said Harry.

He sounded worried. Stewart, remembering a younger Harry who would have revelled in such a situation as this, realized that when a Staff-officer, in addition to his other cares, had a young wife depending upon him, it was apt to take the edge off his natural enjoyment of tight corners. He said gently: ‘I hope Juana isn’t frightened?’

‘Not she!’ The harassed look vanished in a grin. ‘She thinks it a huge adventure to be waiting with her horse ready saddled for a quick retreat.’

Stewart smiled. ‘What a child she is! Is there any word come in yet from the Peer?’ ‘None that I’ve heard of. If we’re cut off-’ Harry stopped, and gave a shrug. ‘Well, I suppose we shall start retreating soon.’

‘To tell you the truth, I wonder we didn’t start an hour ago,’ said Stewart ‘I suppose Cotton didn’t like to act without orders.’

Whatever the reason, Cotton seemed bent on holding his ground for as long as he was able. A cavalry General, his handling of the one brigade at his disposal was skilful enough to keep the French in temporary check; but by seven o’clock, the infantry, who had been standing to their arms since daybreak, were conscious of a restive desire to have Lord Wellington amongst them again.

5

Kincaid, who had been sent on picket the previous evening, and was still unrelieved, had found himself, at an early hour, in a position of some discomfort. When the cannonade began, a quantity of round-shot peppered the ground over which his picket was posted. He remarked coolly that the Frogs seemed to have chosen the picket as their pitching-place, and cast an experienced eye around him to discover the nearest cover. A broad ditch, about a hundred yards distant, offered the only obstacle to an enemy advance. He noted its position in case of a future need, and turned to find his Sergeant at his elbow. A splutter of dust, kicked up a charge of shot falling quite close to them, freely bespattered them both. ‘Don’t seem to be firing blanks, do they, Sergeant?’ said Kincaid.

The Sergeant grinned. ‘No, sir. What will we do, sir?’

‘Oh, just watch the plain!’ Kincaid replied. ‘Seems to be a little trouble going on behind that; hill.’

The Sergeant, who thought, from the confused uproar, that there must be a good deal of trouble going on, grinned more broadly, but said: ‘Yes, sir. As you say, sir!’ The picket remained in position, keeping a look-out over the plain. The rising ground to the left hid the operations of the cavalry from sight, but in a short while such a violent commotion arose from behind the hill that Kincaid lost no time in removing his picket to a position, behind the ditch he had previously noted. He had barely executed this movement when (as he afterwards described it) Lord Wellington with his Staff, and a cloud of French and English dragoons and horse-artillery intermixed, came over the hill at full cry, over the very ground he had that instant quitted.

A picket of the 43rd regiment having formed on his right, Kincaid was forced, for fear of shooting them instead of the enemy, to remain inactive. He was so astonished, he said, by the spectacle of Lord Wellington and Marshal Beresford hacking their way through the mêlée with their drawn swords, that he doubted whether he could have collected his wits sufficiently to give the order to fire.

‘And how they came there, I know no more than my old mare!’ Kincaid told Harry, much later. ‘Old Hookey, and Beresford, and the two guns, and all the beautiful Staff, took refuge behind my picket. Old Hookey didn’t look more than half-pleased, I can tell you. But it was a pleasure to hear Alten swearing. I wish I understood German.’

‘I don’t wonder the Peer wasn’t pleased!’ said Harry.

‘He was bringing up two cavalry brigades to reinforce us, and rode ahead of them to the left of our skirmishing line, where the 11th and 12th Light dragoons were supporting Ross’s guns. Just as he arrived, a French squadron broke in from the flank, straight for the guns. The 12th couldn’t stand against them, and began to retire. From what I heard, some fellows on Beresford’s Staff tried to stop ’em, shouting out: “Threes about!” That’s where the trouble started, because the 11th, who were coming up in support, heard it, and thought the order was meant for them. So they went about, and down came the French, right on top of all the headquarters Staff! Luckily the 11th soon saw that there must have been a mistake, and faced about, and drove the French off.’

‘My God, to think I missed seeing all that!’ said Kincaid, with heartfelt regret. ‘Damn it, you can’t have everything!’ objected Eeles.

‘You saw old Douro laying about him, which is more than we did!’ ‘All very well!’ said Harry. ‘But a pretty mess we should be in now if he had been killed!’ ‘I suppose you think we’ve had a nice sort of a day, with that long-nosed beggar hounding us on one of his cursed forced marches?’ said Eeles, with awful sarcasm. ‘I’ve got a blister on my heel the size of a crown.’

‘The French are in a worse case than we are.’

‘Well, isn’t that a comfort!’ said Eeles. ‘I hope I die before morning, that’s all.’ The two divisions had indeed passed a trying day. Lord Wellington, having brought reinforcements of cavalry to them in person, had immediately taken over from Cotton the direction of the retreat, and had lost no time in setting the divisions in motion. They had marched in two columns, with the Guarena river as their immediate, and Salamanca as their ultimate, goal. Covered by cavalry, they retired in two columns, and had not covered any appreciable distance before they sighted two French columns, marching in the same direction, for presumably the same goals. For eight miles the rival forces paralleled each other, engaging for the entire distance in a desultory dog-fight, as wearing to men’s nerves as any pitched battle. The undulating country lying between the Trabancos and the Guarena was rich with vast fields of ripening corn, intersected by dry water-courses. The corn was yellowing fast, and presented the appearance of a shimmering golden sea. A shot from one of the French guns set a field alight, and the fire spread with hungry rapidity. The roar and crackle of the flames, the cloud of heavy black smoke that rose to hang lazily on the air drew a bitter exclamation from a sweating Rifleman. ‘Jesus! Ain’t it hot enough without them bleeding Frogs lighting camp-fires?’

The 4th division, forming the column nearest to the French line of march, suffered most from the intermittent artillery-fire, and it was not long before the men, fretted by the casualties in their column, began to hope that the rival commanders would decide to call a halt to the march, and form battle-fronts. It was thought that the cavalry were having the best of it; and one Light division man, watching a slight skirmish, loudly expressed his desire to be exchanged into a cavalry regiment. He complained of blisters on his feet, but a prosaically-minded friend replied scornfully: ‘Yus, and if you was on ’orseback you’d ’ave boils on your arse, so for Christ’s sake shut your blurry bone-box!’

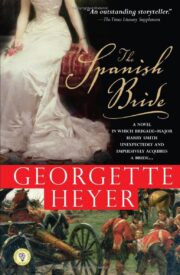

"The Spanish Bride" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Spanish Bride". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Spanish Bride" друзьям в соцсетях.