“I’m sorry to tell you. The president is dead.”

Chapter Twenty-nine

Two days later, the body of Franklin Delano Roosevelt was borne on a gun carriage from the hospital back to the White House before a sea of mourning Americans. Mia stood on the White House steps with the other staff as six uniformed pallbearers slow-walked the flag-covered casket up the stairs. The president had not wanted a state funeral, and so his casket lay only briefly in the White House to be visited by close friends and by Congress, then was transported by train to Hyde Park for burial.

The world war had been so cataclysmic and the president’s leadership so central that his sudden passing seemed a nasty trick of fate. Now, while a bland Missouri hat maker was stepping into the shoes of a giant back in the White House, Mia rode on the train with Roosevelt’s close friends and family.

She stared brooding out the window at the early spring countryside, then felt someone sit down next to her.

Lorena Hickok laid a hand on her forearm. “We haven’t spoken in a while, and I’ve neglected you terribly. I’m sorry. I just want you to know I did my best for you.”

“How very strange. That’s exactly what the president said, just minutes before he died. But I have no idea what that means.”

“He said that too? I’m sure he was referring to the cable that came after you returned from Moscow. About your friend. Eleanor asked the president if he had any influence on Stalin for such things. He was sympathetic but didn’t hold out much hope. Obviously, he either never brought it up or Stalin said no. Bigger issues to deal with, I suppose.”

Mia cringed at the idea that five people in the White House, including the president, knew about her love for a Russian sniper. “I thank all of you for your concern, but that was completely unnecessary. It was my personal sorrow.”

“Yes, dear. I know. But we take care of our own. And now I’ve got to go take care of Eleanor.” She patted Mia’s hand one more time and continued down the aisle of the train.

Mia slumped back in her seat, both embarrassed and touched, and with an additional reason to mourn the passing of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

April continued with one momentous event following the other. Within ten days of the funeral and the swearing in of Harry Truman, the Western Allies and the Red Army met on the Elbe. The Third Reich was on its knees. Five days after that, Adolf Hitler committed suicide, and it became headless. Seven days later, its remaining military leadership surrendered unconditionally.

Truman, who had been vice president only eighty-three days and had played no part in Roosevelt’s negotiations, turned his attention to the continuing war in the Pacific. Yet more—much more—needed to be done about Europe. On May 20, 1945, Harry Hopkins called Mia into his office one more time.

She sat down without invitation. They’d long ago done away with formalities, and she felt sure he was about to terminate her job anyhow.

“So, now that President Truman has shut down Lend-Lease to the Soviets, we’ll be closing this office, I suppose,” she said, making it easier for him.

Hopkins tapped off the millionth ash of his millionth cigarette and smiled ambiguously. “Not quite yet. It’s true that Truman ended the program officially on May 11, but Stalin was so angry, it looked like it would affect postwar talks. So I’ve got to go over there and work out a compromise. An extension, with limited provisions, at least through the summer.”

Mia nodded. Where was this leading?

His smile widened. “You ready for one more round with Uncle Joe?”

“Me? Meet with Joseph Stalin?” She was speechless.

“Yep. Six meetings, starting on May 26. Harriman’s also coming, to discuss China, Japan, the Control Council for Germany, Poland, the United Nations, all that kind of thing.”

Mia stared into space for a moment. Return to Moscow, where she’d suffered the greatest joys and worst torments of her life? Where the woman she loved might be within reach, but also the man who wanted to kill her?

“Ready when you are.”

Hopkins, with Mia at his side taking notes, labored through the six meetings, placating Stalin. It seemed to her they’d given up a lot, but they still needed Stalin’s goodwill to work on the United Nations, to continue against the Japanese, to plan the agenda for the reconstruction of Germany.

She dared not bring up the subject of Alexia and the Gulag, had no idea even of how to approach it with Hopkins. Against the magnitude of the negotiations, it seemed presumptuous, not to say ludicrous, to plead for the life of a single woman.

The meetings she attended were tense, and she sensed the waning of goodwill of both Hopkins and Harriman in the face of Stalin’s demands—demands they would have to meet.

But after the final session, with typical Russian bonhomie, Stalin slapped Hopkins on the back and announced a victory dinner in the Catherine the Great Ballroom.

The banquet was pure Russian and included the entire Politburo, the top echelon of military leaders and commissars, and Moscow’s inventory of ambassadors of other countries. For Hopkins, who had already said in private that he was “on leave from death,” it was obviously a test of endurance.

Mia was glad the fighting was over and that Hopkins had wrung at least a few concessions from Stalin, but her personal bereavement remained unchanged. Molotov made no eye contact with her during the evening, but she sensed his cold presence. He was being lionized by the great dictator and applauded by the entire company, and she hated him for it.

She drank with restraint, as Hopkins did, though out of bitterness rather than sickness. By the end of the evening, which was in fact nearly morning, she and Hopkins were two of the very few people in the Catherine the Great Hall still sober.

As the guests began to stagger away, she saw that Hopkins was in a conversation with Ustinov and showed no sign of leaving. Catching his eye, she signaled that she would meet him later at the embassy car outside and left the hall.

The victory banquet would be the last hurrah before the return to Washington to face multiple terminations. Harry Hopkins would retire from White House service, Lend-Lease contracts would expire, and she would soon have to find other employment. The Kremlin visits would simply be memories colored forever by the images of a stunning Kremlin guard she’d fallen in love with. She regretted bitterly that she had no photo of her and nothing she could use but her name to track her down one day.

For that matter, she’d have to memorize Moscow and the Kremlin as well. Would she be allowed to explore the Kremlin Palace a little before their departure?

The adjoining great halls were open, and she crept as inconspicuously as possible from one to the other. She could not help but be both appalled at the extravagance of the tsars and impressed by their art.

“So, you are the one,” a rough voice said behind her. She froze, as if caught in a crime, wondering who had snagged her. Chagrined, she turned around.

Joseph Stalin stood in the doorway smoking his pipe.

Mia was confused. “‘The one,’ sir?”

“Yes, the one who helped my foreign minister Molotov uncover the corruption in the factories. That we punished severely and without hesitation.”

Mia forced a smile. “Yes, sir. That was me.”

“And you were also the object of a certain remark President Roosevelt made to me. On behalf of his wife, he said.” The dictator puffed a moment on his pipe and blew the smoke out of the side of his mouth.

She was puzzled. What had she to do with President Roosevelt or the First Lady? He continued puffing on his pipe as he strolled past the ornate walls and furniture without bothering to look at them, like someone’s uncle who’d been talked into visiting an art gallery he didn’t care about.

“A good man, your President Roosevelt. This Truman fellow, I don’t think he’s made of the same stuff.”

“It’s hard to say, sir. He’s only just started.”

Stalin shrugged. “Maybe. But I was fond of Mr. Roosevelt. He always wanted to talk ‘man to man,’ as if no one else was in the room but us.”

“He valued the personal touch.”

“Yes, the personal. It’s easy to forget the personal when you’re conducting a war. You get used to moving armies around, issuing orders that will cost thousands of lives—those of your people or the enemy, sometimes both.”

Mia thought of the endless purges.

“Did you know, we lost about a million people in Stalingrad alone? But it couldn’t be otherwise. Stalingrad had to be held, even if it took a million dead to hold it. If I had thought about the suffering of any one soldier and held back, we’d have lost the city and perhaps the war.”

Where was he going with this? Why wax philosophical to her, a foreigner and a capitalist? He had no idea she’d been one of those soldiers he didn’t care about.

“You have to harden your heart, ignore loyalties, the urges of friendship, and concentrate on annihilating the enemy at whatever cost. Ultimately, a father knows what is best for his children, and they must obey.”

She cringed inwardly, at the same outrageous words she’d heard her father say. She was also aware of how he could bend and twist the word “enemy” and strike at the heart of the people he was ostensibly defending. Curiously, she was not afraid of him.

“And yet, Marshal Stalin, doesn’t the personal intrude now and again? After all, we’re not automatons, not even a field marshal moving armies. We’re flesh and blood, and we love.” She realized with a shock that she was arguing with Joseph Stalin and fell silent.

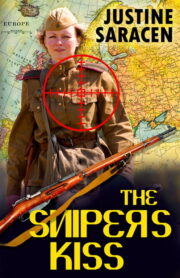

"The Sniper’s Kiss" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss" друзьям в соцсетях.