The commissar hefted the gun, as if it now weighed less. “How do you know so much about this rifle? You were a soldier?”

“Yes, Comrade Commissar. A sniper in the 109th Rifle Division. Thirty-two recorded kills.”

“Oh, well done. Does the commandant know he has a sharpshooter in his camp?”

“I’m certain he doesn’t, Comrade Commissar.”

“Well, well,” he said, ambiguously. “Thank you for… uh… saving my head. Now you’d better get back to work.” He ambled away, his newly cleaned Mosin-Nagant cradled in his arms.

Fortuitously, Ivan joined him, and they marched back to camp together for the midday report. As soon as they were out of sight, Alexia called out, “Now,” and the women scrambled toward the nearest log pile to transfer the logs that would allow them to make their quota and earn their full ration one more day.

At supper, while Alexia wiped out her bowl with the last of her bread, one of the guards called out her number. “To the commandant’s office,” he ordered. With an anxious glance at her friends, she followed him.

Upon entering the commandant’s office, however, she saw the commissar was present also, and the recalcitrant Mosin-Nagant lay across the commandant’s desk.

“So, I hear you’re a hotshot marksman with thirty-two dead Germans under your belt,” the commandant said, snickering. “And that you can dismantle one of these things in the blink of an eye.”

“Yes, Commandant.”

“A shame it’s a skill you can’t use in a labor camp. What did you do before you learned to shoot?”

“I was a teacher, Commandant. In Arkhangelsk.”

“In Arkhangelsk?” He seemed astonished. “What school?”

“Primary school number 12. Unfortunately, it was destroyed in an air raid in September of last year.”

The commandant shook his head in disbelief. “I know that school. My son went there the year before.” His face softened and lost the harsh authority of his office.

For a moment, Alexia forgot too she was a prisoner. “I was probably one of his teachers. What was his name?”

“Mikhail Ivanovitch.”

“I remember him. A shy boy who liked to draw horses.”

“Yes. That was him.” The commandant seemed deeply touched, as if recognizing for the first time that his prisoners were his countrymen and neighbors. He scratched his jaw.

“Well, I think the camp can find a better job for a schoolteacher than felling trees. How good are you at typing?”

“Superb, sir. Almost as good as shooting.”

“All right, then. I can’t do anything about your housing. The barracks are full to bursting with criminals, and putting a political in there would cause you more grief than comfort. But at least I can put you to work where you’ll be indoors for the rest of the winter. Report to the administration tomorrow after the morning count.”

Thus was Alexia saved from starvation. The hours as an administration typist were just as long, her food ration slightly less than before, but she labored sitting, in a warm room, while the others marched out into the icy forest every morning. She felt guilty returning each night to the dugout to face the other physically depleted women, but on the rare occasions when extra bread appeared mysteriously on her desk from some benefactor, she took it back to her comrades. It was the least she could do.

Nina and Sonia had become expert at shifting logs from one pile to another wherever they were assigned and always exceeded their quota. The brigadier Ivan was either very stupid, or very kind, for he never said a word.

And every ten days, their turn came for the bathhouse, a noisy, poorly heated shed that offered little comfort other than a brief respite from the lice. The camp issue of soap was small, evil-smelling, and had to be used for hair and body. Fortunately, they could dump their lice-ridden rags into a pile to be boiled and disinfected by the laundry workers. Then for fifteen minutes, they huddled together in the tepid warmth of the washroom, scrubbing each other’s backs and hair, and joked that now at least the lice would be clean.

March and April passed, and the sub-zero temperatures gave way to warm, drenching rains, but there were no deaths among the women. Life in the underground zemlyanka continued to be squalid, and now the mildew smell was permanent, but Alexia lost no more weight, only her previous convictions. Over the months of her sentence, political doubt had hardened into cold cynicism. And after living intimately with her friends in a hole in the ground, she sensed they felt the same.

One night, they even dared to talk, to say things that on the outside would have gotten them a doubled sentence.

Nina began the treasonous discussion. “Did you see the new banners in the camp? Patriots working for the glory of Communism.” She laughed. “I wish they’d make up their minds. Either we’re patriot brothers and sisters, celebrating the victory of Leninism, or we’re enemies being brutalized for not celebrating it. You can’t be celebrating and at the same time have a gun to your head.”

A vague idea that had haunted Alexia now coalesced in her mind. “That’s true not just of the Gulag, but of Soviet society in general.”

It was a vast leap in thought, and Sonia and Nina, and the others within earshot, waited for her to elaborate.

“Even on the outside, how can we celebrate the glory if, even in our own homes and jobs, we live in fear? And what exactly are we supposed to glorify? Our shops are empty, and not just because of the war. The collective farms don’t produce enough food, factory workers labor fourteen hours a day on patched-up machinery, and everyone at every level, even in the Kremlin, is corrupt.” Her voice dropped in volume, as if she spoke only to herself, but the words were incendiary.

“I’ve begun to think sometimes the entire Soviet experiment has failed and no one has the courage to admit it.”

“That’s treason you’re talking,” a small voice said from the other side of the dugout. It was Olha. Ominously, no one contradicted her.

In the deadly silence that followed, one of the women extinguished the kerosene lantern. Alexia knew she’d sealed her fate. But what more could they do to her? She already faced twenty-five years at labor, and the one person she desperately loved was lost to her forever.

She rolled up in her blanket and stared into the darkness. Let them execute her now for treason. She no longer cared.

The next morning, she awoke full of regret. She had said reckless things the night before and realized, in fact, she did care. Not especially for herself—since twenty-five years was as good as life—but for her mates. If any one of the women denounced her, the other women would be held guilty, too, for agreeing with her. Even if their sentences were not doubled, at the very least, the group would be broken up and the prisoners sent to other camps or colonies. Everyone would have to start over, building a new support network to trick the system and survive.

She reported for work in the administration office but was nervous all day. And at the end of her ten-hour shift, her worse fears were realized. Prisoner G 235 was summoned to the commandant.

She cursed Olha, who had obviously denounced her.

Calming herself, she tried to formulate some sort of half lie to protect the innocent ones. Something about having a fever and saying deranged things she should not be held responsible for, and that the others had only humored her out of kindness. Would he believe it?

She knocked, and at his reply, she stepped inside, her ushanka in her hand. She saluted unnecessarily—her imprisonment was not military—but she wanted to remind him she’d been a good soldier.

“I have no idea what’s going on here, but it’s my duty to follow orders,” he said.

“Yes, Commandant,” she replied, dry-mouthed. He was about to pass sentence, all because she couldn’t keep her mouth shut. She rocked slightly, almost physically sick, and her hands began to tremble.

“Orders have come to transfer you to Moscow. Leave behind whatever possessions you might have. You won’t need them. A truck will pick you up after supper.”

Chapter Twenty-eight

Throughout March 1945, the war news from Europe was largely good. Finland had declared war on Germany, while the Allies had crossed the Rhine at Remagen and plowed through Cologne and then Mainz. The Germans were evacuating Danzig before the imminent attack by the Red Army and were clearly in the throes of defeat. However, for reasons known only to the president and General Eisenhower, the Western Allies had deliberately slowed their advance to allow the Red Army to take Berlin. Mia thought it might have been a final concession to the Soviets, who had demonstrably done most of the fighting and dying in the European war.

Lend-Lease continued, and Mia carried on with the drudgery of her job. Then, at the beginning of April, a call came from Security that she had a visitor. A woman. She had few female friends in Washington so was filled with dread. It could be only one person.

“Grushenka,” she said coldly, as she caught sight of the visitor waiting at the ground-floor guard station. She marched another ten paces toward her. “I thought we’d gotten rid of you.”

“Don’t be like that,” Grushenka said mournfully, linking her arm with Mia’s. “Shall we go to your room, or is there someplace nearby where we can talk?”

With no intention of letting this blackmailing harridan into her private quarters, Mia led her toward a ground-floor storage room. She motioned toward two folding chairs, and they sat down facing one another.

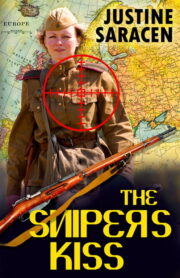

"The Sniper’s Kiss" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss" друзьям в соцсетях.