Pavlichenko frowned. “I believe I met her somewhere on the front. But a labor camp is an unusual punishment for a desertion.”

“Well, it’s a long and complicated story. I was wondering, could you help me get a letter to her? Just a brief message so she knows someone cares about her?”

Pavlichenko shook her head. “Some camps allow letters and parcels, and some do not. Unfortunately, if the authorities say no communication, I have no more ability to penetrate that wall than you do. All I can do is advise you to take heart. The war will be over soon. Our troops are already in Germany. Afterward, your government can make an appeal through the Central Committee to contact her, maybe even to shorten her sentence.” Pavlichenko offered simultaneously a smile of encouragement and a shrug.

They continued down the corridor for a few minutes without speaking. “Do you remember our conversation about Dostoyevsky when we first met?” Mia asked.

Pavlichenko clasped her hands behind her back as they paced. “Yes, though I still can’t fathom why he interests you.”

“Well, one of his characters makes a virtue of submission, of insisting that a person should offer love, a kiss, as it were, to the world no matter what evil is visited upon him.”

The major laughed in a sudden burst of derision. “Well, with 309 dead Germans behind me, you can imagine my opinion of submission.”

“But what about submission to the state? How is that different?”

“Submission to the state is done in the belief that the state is the collective will of the people. Dostoyevsky’s submission involves only the individual, a privilege of the comfortable intellectual who cares about his personal salvation more than for the suffering masses.”

She glanced down at her watch. “Oh, it’s twelve o’clock. I promised General Kruglov to meet him for lunch. It has been a pleasure to talk with you again, Miss Kramer, and I hope you find your friend, Alexia Vassilievna.”

They embraced lightly, and Mia hurried back to her room, arriving only a few minutes before Hopkins knocked at her door.

“Good that you’re in. Can you take some dictation right now? I want to set it all down before I forget.” He was already inside and seated on the one chair in the room.

“Of course.” She readied her fountain pen and notebook.

“The long delay of the Western allies in entering Europe has allowed the Soviets…” So he recounted for some fifteen minutes, but soon his voice grew hoarse. His almost-transparent skin and blue lips revealed how much the talks had taken out of him, and he seemed to be at the end of his strength.

“Please type that up as soon as you can, with carbon copies,” he said, coughing into his handkerchief. “I’m going to have a rest now. The president will have a private conversation with Stalin at two o’clock this afternoon in the blue suite, before the final press photos. I’d like you to be there, as a standby, in case the president needs another interpreter or messenger.”

“Yes, of course,” she said anxiously as he slouched toward the door and let himself out.

Mia arrived at the Blue Suite just before four, but as she feared, Hopkins had not made it. President Roosevelt greeted her as his assistant brought him down the corridor, but reaching the suite, he dismissed the man and rolled himself inside. Stalin was already inside with the single interpreter who was allowed.

What was so critical, she wondered, that excluded Churchill and all the president’s military staff and advisors? Could it have something to do with the mysterious Great Weapon the US was developing and everyone was whispering about?

Whatever the subject, the president emerged after an hour, and the leaders and their entourages collected before the main portal of the palace.

The three heads of state sat together much the same as they had done at Tehran, only this time they wore winter clothing. As the press snapped away and their flashbulbs popped, various officers wandered in and out of the frame behind them.

Mia knew most of the names of those in the American and British entourages, fewer in the Russian group, but had no trouble recognizing Molotov. He studiously avoided looking in her direction, but it no longer mattered; the power they once had over each other was gone.

What concerned her was that Stalin, in his military greatcoat, seemed gleeful, while Churchill glowered, and President Roosevelt huddled haggard and frail inside his cape.

All the while she watched the three leaders posing for the press, the thought of Alexia haunted her. What was life like in a Russian labor camp in the dead of winter?

Chapter Twenty-seven

November 1944

Alexia stepped down from the prison train at the Vyatlag station and stood with the other new prisoners. Numb and docile, she still had not come to terms with her conviction for treason and the court’s sentence of death. It had scarcely made a difference when the leader of the troika had “by the generosity of the state” commuted the sentence to twenty-five years at hard labor.

Treason. Twenty-five years. Enemy of the people. She struggled to understand the downward spiral that had begun with a decision to leave the honor guard and fight actively for the homeland. Was Father Zosima right, that violence begets violence?

Vyatlag, colony 14, was assigned to forestry, and learning that, she was at first relieved. But now she saw she should not have been. It was bitter cold, and the colony where she would be put to work consisted of a row of wooden buildings, too few buildings to house all the prisoners. Where were they? And what were the strange-looking mounds in the field behind the buildings?

Soldiers led her to the nearest building, and she hoped it would be their barracks. But it was merely an administrative center where she had to wait to be registered. Then she followed the line leading to another large room, where male guards ordered her to strip. They sniggered at the naked women as they handed them the bundle of their prison clothing: underwear, padded trousers and jacket, and felt boots. In the room beyond, they were allowed to dress.

As she slowly warmed in her padded clothing, rough hands shoved her toward one of a row of chairs. Men with razors and buckets of water stood behind them and shaved the newly arrived prisoners completely. “To keep away lice,” someone said, dragging the razor along her scalp. Afterward, someone handed her a ushanka for her bare head, similar to the one she’d worn at the front. But on this one, the flap across the forehead displayed the same number that was painted on her jacket, G 235.

The entry procedure ended in a double lineup, with women on one side and men on the other. A guard counted off twenty and led them onto the field with the strange hillocks. Smoke wafted from most of them through a narrow pipe at the center, and she realized with horror they were in fact hovels, covered holes in the ground where people lived.

“This is your zemlyanka,” the guard said, shoving Alexia toward one of them. The canvas door opened, and a bony woman drew her into the dark interior and urged her onto a wide wooden plank. When her eyes grew accustomed to the dim light of a kerosene lantern, she could see the walls were packed soil with narrow logs pressed against it to keep it from falling in. Overhead, a mass of saplings, branches and twigs, made up the roof, with dirt and snow packed into it to create a solid mass. Off to one side was a barrel of what she presumed to be water, and at the center, with a metal pipe leading through the roof, was an iron stove. She could see it was burning, but in the frigid November air, she felt none of the heat where she sat. In spite of the cold, the entire hovel stank of mold, urine, and sweat.

“Didn’t expect that, did you?” the woman who had guided her in said. “Well, you better get used to it. You’re a zek now, and every place else you’ll be is going to be worse.” She took off her winter hat and scratched her scalp. Her head was covered with short, oily brown hair, obviously several weeks of growth after a head-shave.

“A ‘zek’? What’s that?” Alexia asked.

“Short for zaklyuchennyi, prisoner,” a second woman explained. She had slightly longer hair, jet-black, and a flat Asiatic face. “By the way, I’m Nina. That’s Olha.” She pointed with her chin. “And this one here is Sophia.” She poked her neighbor with her elbow.

Alexia managed a weak smile at all three women. “This is where I’m supposed to sleep?” She patted the plank they sat on.

“Yeah, and this is your blanket.” Olha poked something filthy and brown rolled up against the wall. “It’s got lice.

“We’ve all got lice,” she added more cheerfully, “but at least they let us bathe once a week and they wash our clothes. It’s important to stay clean and not let yourself go. Do you smoke?”

“Uh, no,” Alexia replied, puzzled.

“Good. Most of us don’t. But we still get a tobacco ration. Not much, less than the men, but if you save it, you can exchange it with someone for the things you’ll need.”

“What am I going to need?” Looking around, she realized it was a stupid question.

Nina said the obvious. “Everything.” Then, “So, what’s your name? What were you before?”

“Alexia, from Arkhangelsk. I was a soldier. Rifleman.” She saw no reason to elaborate.

“Ah. I was a farm girl in Kurgan,” Nina said. “The wife of a kulak.”

“Me, a seamstress in Smolensk,” Sophia added.

Eyes turned to Olha, who simply said, “None of your business.”

“So what happens next?” Alexia asked, facing the others.

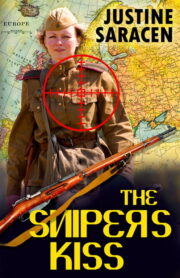

"The Sniper’s Kiss" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss" друзьям в соцсетях.