Back in the ambassador’s office, they took up the positions they’d left shortly before. The walk had been refreshing, but Mia was glad to be sitting again. She resumed scratching the back of her neck where the plaster cast chafed.

“How’s the shoulder? Sorry. I should have asked sooner. Do you need further treatment? I can get a doctor in, if you want.”

“No. The cast seems adequate. I don’t know how long it takes a clavicle and shoulder blade to heal, but I’m managing.”

“Well then, congratulations. You did your job and found your suspects. Write up your report, and otherwise have a good rest. You can stay at the embassy until you receive orders from the White House.”

Hardly had the ambassador finished his talking when a knock sounded at the door. “Yes? Come in?”

The corporal’s head appeared at the edge of the door. “A telephone call, sir. From the Kremlin. Mr. Molotov, sir.”

Harriman and Mia exchanged glances. “Thank you, Corporal. Would you put the call through?”

Mia stood up to leave and grant him some privacy, but he raised a hand to stop her. “No, please stay. This concerns you, I’m sure,” he said, picking up the handset at the sound of the buzz.

After the initial polite exchanges, the ambassador’s side of the conversation was succinct. “Yes, yes. Of course. I quite understand. Certainly. It will be my pleasure. Shall we say tomorrow at four o’clock? All right then. Good-bye.”

The ambassador leaned back in his chair. “He knows and can’t wait to come and discuss you.”

“So, the ball is in your court.”

“Yours, actually. Yours and Harry Hopkins’s. Now that you’re under the shelter of the embassy—” He drew out a pad and pencil from his desk drawer. After a moment of scribbling, he slid it toward her.

Your information could conceivably purge Mr. Molotov from the Kremlin, not to say from the earth. You are in a very strong bargaining position. Consider what you want from him, but don’t go too far.

Mia nodded, thought for a moment, then said out loud, “I know what I want.”

“Good, and in the meantime, I’m going to call Dr. Kuznetsov, a doctor who treats the staff on occasion. I want him to take a look at that cast. It seems awfully heavy, and since you’ve worn it for over a month, maybe he can replace it with something less dramatic.”

Portly and with a full drooping mustache and thick hairy eyebrows, Dr. Kuznetsov reminded Mia of Friedrich Nietzsche, or at least of a sketch of him she’d seen. He examined Mia’s cast, asked a few questions, then stood back smiling.

“You have to admit, if you give our military hospitals the supplies they need, they are extremely thorough. That cast would hold a horse’s leg in place.” He knocked on it for emphasis, the almost imperceptible thud suggesting a great deal of plaster had gone into its making. “You say you’ve worn this for a month?”

“More than that. And for that long I haven’t had a good night’s sleep.”

“Well, I’m afraid you still won’t after I remove it and immobilize your shoulder with a bandage. Quite the opposite. You’ll feel some pain if you lean on it. But you’ll have less weight to carry around, and you can put a shirt on. A big shirt, of course, using only one sleeve.”

From his bag, he drew out a tiny circular saw attached to an electric wire and bent over to plug it into the wall. When he approached her, she eyed the little machine with suspicion.

“You’re going to slice through the plaster with that? How do you know how deep to saw? I mean, there’s me inside.”

He chuckled softly, and she realized he probably heard the same protest from every patient about to lose a cast. “Don’t worry. The radius of the blade is less than the thickness of the cast, and the bottom layer is fiber. Never slashed anyone yet. Now rest your elbow here on the back of this chair.” With that, he stepped behind her and began with a vertical slice up the length of the plaster on her back.

It was nerve-racking to hear the buzz of the saw so close to her ear—and skin, and she couldn’t help but flinch each time he forced it into the cast wall. Finally he cut away a portion of the rear support, and her arm dropped about an inch onto the chair back. She felt a painful tug on her shoulder muscles.

Docile and patient, she grimaced through the remaining slices, none of which produced any bloodshed. Finally he set his saw to the side. Then, gripping the edges of the plaster segments, he tugged them apart, tearing the final layer of gauze that covered her skin.

“Now you must hold very still while I put it into the right position and bandage it again.”

With her arm still bent at the elbow and supported by the chair back, all she felt was the cold air across her newly exposed skin. The whole limb felt frail and weightless, and it itched, but she dared not scratch it.

He palpated the area around her clavicle gently, eliciting a grunt of pain from her, then stopped. “Now I’m going to move your arm down. Your stiff shoulder muscles won’t like the new movement, but it will be all right.”

With that he lowered her elbow gently to her side, then laid her forearm across her midsection. “Hold it here with your other hand while I bandage it,” he ordered. The injured parts of her neck and back began to ache as he wrapped several rolls of bandage around her upper arm and shoulder. A third layer around her midriff and forearm fixed the arm in place.

“There you have it. Keep it wrapped for another week at least, ideally longer. Would you like a souvenir?” he asked, holding up a piece of the cast.

“No, thank you. The pain is souvenir enough.”

“Very good.” Leaving the plaster fragments for the embassy to dispose of, he packed up his circular saw and snapped his bag shut. After a handshake to her good hand, he strode from the room. She heard him exchange a few words with the ambassador and then the sound of the closing door.

As she drew on her shirt, Harriman appeared in the doorway. “Everything all right?”

“Yes, thank you. Um… he knew I’d been in a military hospital. What did you tell him about me?”

“Very little. I said you were a journalist and were injured while photographing a battle at the front. I don’t think he believed me, but he knew that was all he would get from me. If his people tell him something else later, no matter.”

“I suppose you’re right. Anyhow, this feels better.” She patted her arm. “I didn’t want to confront Molotov looking like a scarecrow waiting for a crow. I can also almost wear a shirt now. See?” She buttoned the shirt under the bulge of her forearm. Her shoulder and neck were aching badly from the movement, but it felt good to be more or less dressed.

“So, have you decided what you’re going to say to him? Molotov, I mean,” Harriman asked.

“I’d like to tell him to go to hell, but don’t worry. I won’t.”

The ambassador’s expression suggested he felt the same way.

At four o’clock precisely, a black limousine drew up in front of the Spaso House portico carrying the foreign minister. Mia watched from the window, recalling the way she herself had arrived two nights earlier, a fugitive in rags, and in the sidecar of a motorcycle. Now, the balance had shifted.

A driver climbed out and opened the car door for him. Molotov stepped out and marched to the door of the embassy. Mia backed away from the window to watch the door open from the inside. The guard was the same corporal who had admitted her, though this time, of course, he was more servile.

Ambassador Harriman shook hands with him, and only after the exchange of formalities did Molotov notice her standing off to the side.

“Ah, Miss Kramer. I am pleased to see you are alive and well. I trust your injury is not causing you much trouble.” His smile was wooden.

“Thank you for asking, Foreign Minister. None of consequence. But I believe you have business with the ambassador. We can speak later.”

With a slight tilt of the head, the foreign minister followed Harriman into his office, and the corporal shut the door behind them. Mia took a seat in one of the stiff ornamental chairs in the lobby. The official meeting, during which Molotov would stitch together some explanation of her disappearance, couldn’t possibly last long.

So this is what smug feels like, she thought. To catch someone in a lie. In a cat-and-mouse game, to finally be the cat. It was a good feeling.

Scarcely fifteen minutes later, the door opened again, and the two men stepped out. Harriman gestured toward the front door and said the words she was waiting for. “I believe you and Miss Kramer have some business to discuss, and the air in the garden is quite fresh this time of year.”

The corporal opened the door again, and Molotov marched expressionless through the doorway. Seeing the foreign minister emerge, the driver stepped out of the car again, but Molotov waved him back in. He was going for a walk.

Mia fell in step next to him, and they traced virtually the same path she had already walked with the ambassador the day before. Like a boxer waiting for the match to start, she considered her opponent.

She knew whom she was up against. Molotov had weathered the revolution, Stalin’s several purges, and four years of war—and he was as unpredictable as a cobra. But she had the weight of the White House on her side and the benefit of not being terrified of her head of state, while he was on his own. When they were halfway around the circle of the garden, he spoke first, and his voice was pure oil.

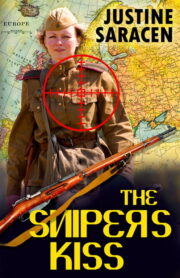

"The Sniper’s Kiss" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss" друзьям в соцсетях.