She staggered along the cratered road to where the rest of the wardens were already assembling with gloves and helmets, and Grigory was unrolling the main hose. Waving to the team leader, she rushed up the stairs to her post, cowering behind one of the walls as the next wave of planes arrived.

As usual, the second wave carried only incendiaries. Where the earlier explosions had penetrated the roofs, the incendiaries would finish the job inside the buildings, igniting fires inaccessible to the water hoses.

The incendiaries themselves were small, but very hot. Hundreds fell at once, littering the tar-and-wood roof in a network of sizzling sparks, and the wardens lurched toward one after another to snatch them up before they burned through.

Though she held them for only a second, they scorched her gloves, and the acrid smoke reddened her face, but she and the others succeeded in flinging them onto the courtyard below, where they burned out.

Then the planes were gone, and the school still stood. Exhausted, she joined the others jogging back to town, too exhausted and coughing to cheer, or even talk.

Ten minutes later, still standing in the road, she heard the rumble, and her heart sank. A third raid. And this one was in earnest, for bombs began exploding all around them. The school took a direct hit. From their position, Alexia and Grigory watched, stupefied, as the interior of the building shot up in a mass of wood and flame and fell again, battering what was left of the walls. They didn’t budge from where they crouched. There was nothing left to save.

“That’s it,” Alexia said. “I’m joining up.”

Alexia brought the glass of hot tea from the samovar and handed it on a napkin to her grandmother. “I’m sorry, Babushka, but the time has come. All the men I know are at the front already, and now that the school’s destroyed, I have no job, no reason to stay at home.”

“I don’t want you to leave, my Alyosha. You’ve been the light of this house for so many years, since your mother died.” She gestured toward the simple room cluttered with painted pottery and embroidered cloths. “How will I manage without you?”

“You do very well without me, Babushka. The neighbor’s boys feed the goat and chickens, you’re in good health, and Father Zosima will still come by every day, as he has for years.”

The old woman sipped her tea. “But it is a sin to kill,” she grumbled.

“I know that, Babushka, but it’s not a sin to defend yourself from a murderer. And the Germans are murdering us.”

“I pray to the Virgin every night that the war will end, but it never does.” She glanced lovingly toward the “beautiful corner” of the room, where a cabinet draped with a silken cloth held candles and three icons.

“Babushka, you know the village headman doesn’t like you keeping those.”

“I don’t care. No one is going to arrest an old woman for her icons. Even if you claim to be a good communist and member of the Komsomol, I know you have a soft spot for them.”

There was some truth in that. The Virgin and Child image had comforted her when she’d been orphaned at the age of seven and adopted by her grandmother. Saint George’s icon was appealing because he had a horse, and she liked horses.

The third, supposedly of the Annunciation, attracted her the most. Gabriel, with silver-painted wings and streams of golden hair, was suspended in the air over the Virgin, the angelic lips lightly touching the virginal ones. From her earliest notice of the icon, Alexia had assumed the angel was a woman offering a holy, life-changing kiss. It had filled her first with contentment and then with longing. Even after formally renouncing the faith upon entering school, she had fallen asleep at night imagining that the divine female Gabriel, in a robe of fluttering silk, hovered over her and pressed angelic lips on her own childish ones.

She laid a protective arm over her grandmother’s back. “I’ll always have a soft spot for you and this house. But I have to go. Patriarch Sergei himself said on the radio that the task of all Christians is to defend the sacred borders of the homeland against the German barbarians.”

The old woman sighed and set her tea glass aside. She placed a noisy kiss on Alexia’s cheek and stroked her hair. “All right. You have my blessings, Alyosha. But you must first promise to go and see Father Zosima.”

Alexia braced herself. That was going to be the hard part.

The old wooden church of Arkhangelsk had been closed for years and adapted as a storage depot. But the old priest known as Father Zosima still lived in a room at the back of it. When she knocked on his door, he greeted her with an embrace and led her into the church where barrels of kasha and dried fish had replaced the holy objects.

He drew her down next to him on a bench. “You see what the communists have done to us?”

She understood his sorrow and recalled the Christmas celebrations of her childhood, but she had no time for nostalgia. She gathered her courage and blurted out the news.

“The German bombers have destroyed my school. I have no more work, no more reason to stay here, so I’m enlisting.”

He took both her hands in his. “I am aggrieved to hear it, my child. I wish you would not soil yourself by killing. Even in defense. God gives us a free choice at every moment. You can choose to serve but not shoot. Perhaps you can be a medic or a guard or a mechanic.”

“Mechanic? I don’t know a wrench from a potato. As far as medicine is concerned, I’m afraid I’d cause more harm than good. I’ll go where they send me. Besides, weren’t you in the tsar’s military when you were a young man? My grandmother mentioned it once.”

“Yes. I was an officer. I was also a brute to my servants and a charmer to the ladies. I even fought a duel for a woman.” He chuckled at her expression of astonishment.

He smiled wanly. “I was really quite dashing, in fact, and caught the eye of a certain married lady. When her husband challenged me to a duel, I could not refuse. But the night before was a particularly beautiful summer evening. Moonlight shone on the water of the park where we were to duel. I decided I could not defile such beauty by killing someone, especially a man whom I had wronged in the first place.”

“So you canceled the duel?”

“No. I let him shoot me. And you know, God rewarded me for my decision by letting me be wounded but not killed. I recovered and vowed to never hurt any man. I renounced my military commission, and after a year of study I became a priest. So you see? We always do have a choice, even if it is only the choice of self-sacrifice.”

“I… I don’t know what to say. I suppose I will have choices, but not many.”

“Then choose to serve without shooting. And pray for the salvation of those who want to harm you. Remember, the most important gift we have is our capacity to love. Do not forget to love.”

Alexia sighed. She had grown up under the guidance of Zosima, but his faith didn’t include defending himself, or anyone. She thought of the angelic kiss of the icon. It seemed worlds away from the bombs dropping on Arkhangelsk.

She embraced him and left him sitting in his dusty church-turned-storeroom.

The commissariat was housed in an old brick building that had once been an export station for cod, snail fish, and salmon to the inland cities. The Bolsheviks had confiscated it in the 1920s and removed its processing equipment, and now the sign overhead read Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army. As she entered, Alexia was sure she could detect the faint odor of fish.

The commissar was short and somewhat spherical, his plump jowls blending in a smooth line with his wide neck, and the top button of his uniform collar was invisible under the rolls of his chin.

“So, you’d like to enlist,” he said. It wasn’t a question, so she merely nodded.

“How have you served until now?”

“In the Komsomol. I’m also a schoolteacher. Was. My school was bombed.”

“Schoolteacher, I see. But what about military training? Did you follow any of the Vsevobuch courses?”

“Yes, Comrade Commissar. Driving, marching, small-arms firing, political instruction.”

“Anything you particularly excelled at?”

“No, sir.”

He looked her up and down, then tilted his head. “Just how tall are you?”

“One meter seventy-seven, Comrade Commissar. I was the tallest in my class.”

He scribbled something on her papers. “They’ll find a place for you after your training. Here, fill out the form for your identification, then take it down that corridor to the photographer.” He handed her several sheets of paper as well as a pencil and pointed with his chin toward a table in the corner.

She wrote in her birth date and place, family members, Komsomol membership number, civilian profession, and list of Vsevobuch courses, then joined the line to the photographer. When she returned to the beefy sergeant and handed over her photo and questionnaire, he clipped everything together, then slid a page of military regulations toward her. “Sign here at the bottom,” he said, handing her a fountain pen. Without reading any of the text, she wrote her name.

“All right, then. You’re in the Red Army now. Report at eight tomorrow morning for the ride to the training center. Don’t be late, or you’ll be arrested.”

The next morning an open troop carrier transported her and sixteen other recruits to the training center at Vaskovo, where half a dozen other trucks had arrived as well. She clambered out of the carrier, shrugging inside her coat to keep away the sharp October wind, and was glad to soon be indoors in the female barracks. She and her barrack mates were herded into a central hall, where a lieutenant delivered a patriotic speech and then ordered them to the quartermaster to be issued uniforms.

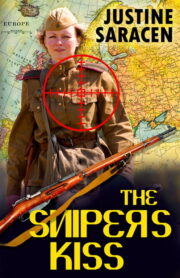

"The Sniper’s Kiss" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss" друзьям в соцсетях.