The explanation was met with incredulous silence.

“Look, I don’t care whether you believe me. Just know I’m here to fight with you against the fascists and take the same risks. Can we leave it at that?”

Fatima shrugged. “I suppose if she’s willing to dodge bullets the same as us, she’s not a spy, eh?”

“Fair enough,” Kalya said. “So, how’s your poor head, anyhow?” She touched Mia’s forehead lightly.

“Much better, thanks. The crash jarred my vision, but by the next day, it began to improve. I still have trouble focusing, but I can manage.”

Klavdia persisted. “That still doesn’t explain why you decided to join up with us.”

“It ought to be obvious. There I was, in your medical station. Major Bershansky notified STAVKA that I was here and then wanted to ship me back with the other wounded. But sending me to Moscow would put me back at the mercy of Molotov. He’d just find another way to kill me.”

Fatima scratched the back of her neck. “I still don’t understand. Why would Molotov want to kill you?”

“Because I uncovered something that may incriminate him. When he found out I knew, he had me kidnapped and ordered his men to kill me.”

Alexia nodded, as if slowly accepting the possibility.

“Anyhow, as it happened, one of the wounded on the ambulance the Germans hit was Sergeant Marina Zhurova. Just before she died, she offered me her identification.” Mia reached inside her tunic and held up the pay book. “And then Sasha helped me get a uniform and a gun. So, here I am.”

Kalya brushed dirt from the sleeve of Mia’s tunic. “This is all much too complicated for me, and anyhow, what our leaders do doesn’t concern me. Just one question.” She nodded toward the rifle. “Can you shoot that thing?”

“Uh, no. I was hoping one of you could teach me. You don’t have to make me an expert marksman. Just tell me how to load and fire the damned thing. But you’ll have to wait until it’s light. I still can’t see very well.”

Kalya threw her head back. “Oh, wonderful. You want to join a snipers’ team and you can’t shoot.”

“Yeah. Something like that.”

“I’ll teach you to shoot,” Alexia said. “Come sit here next to me, and I’ll explain.”

Alexia laid the rifle across Mia’s knees and placed her hand on the cartridge chamber. “This is the Mosin Nagant that we all use, and it fires five cartridges from a clip. It’s no good for rapid firing, like the machine gun, but if you’re stationary and protected, its range is pretty good. Of course, you have to be able to see your target.”

“My eyes are better than they were yesterday. Maybe they’ll keep improving.”

“Just try to stay under cover until they do. Now, your rifle is currently not loaded, in case you didn’t notice. Do you have cartridges or clips?”

“Uh, you must mean these things.” She slid a clip out of her bandolier.

“Very good. Well, you simply slide the clip into the chamber and pull out the metal strip that holds the cartridges. If you want to empty the chamber, you have to open it from the bottom, here under the trigger box.”

“What if I have only individual cartridges?”

“Simple. You press them in with your thumb. Like this. Now, show me you understood by removing the cartridges and then inserting them again.”

So it went for Mia’s crash course in the Mosin-Nagant rifle, which distilled three months’ instruction into an hour. She listened carefully, felt along the various parts of the weapon, and tried to memorize the name for each part.

By the time they all curled up to sleep next to the wall of the station, she had learned, actually, very little.

Enemy fire was sporadic the next morning, and Mia had the impression that, in spite of the damage they had done, the German forces had exhausted themselves in their attack the day before.

As word spread of the fortified position being held by the survivors of the 109th and the 145th divisions, scores of others from decimated units migrated toward the station as if to an oasis.

And while they waited for the promised reinforcements, Mia learned how to shoot her rifle. With vision that improved each day, she missed the target with ever-increasing proximity and even managed to graze it finally.

“You’re doing everything right, and you have a steady hand. You should be doing better.”

“It’s my eyes. I can see you quite well now, but I don’t have a scope, and when I stare through the rifle sight, the target gets blurry.”

“Maybe it’s just a matter of time.” Alexia encouraged her, but she didn’t sound convinced.

On the third afternoon the remnants of the 62nd Armored Division arrived, along with Colonel Borodin, its commander, and Captain Natasha Semenova, a political commissar, who immediately reminded them of Stalin’s “Not one step back” policy.

The accumulation of stray units in the Menyusha brickworks did not count as a retreat, she said, but rather as a strategic regrouping. And henceforth, there would be no retreat from any position without permission from STAVKA, and under no circumstances was surrender permitted. “We have no prisoners, only traitors,” she declared, echoing Stalin’s policy of abandonment of any captured Soviets. As word spread, everyone waiting in the brickworks knew they were now under Colonel Borodin’s command, and they would go on the offense the following morning, no matter the cost.

At five o’clock the next morning, the commissar brought the orders. Medical units would remain at the brickworks until the new base was secured, while artillery and armored units would advance, followed by infantry.

After Mia loaded her pack, hauled it up onto her back, and went to stand next to her friends, Commissar Semenova called out to her.

“You there, you’re with the 4th Rifle Platoon. Fall in over there.” She pointed toward the men gathering some distance away outside the building.

“But I’m…” She looked helplessly at Alexia and realized that saying she was “with the snipers” carried no weight. A dozen people had watched her learn to shoot the night before and knew she was no sniper. She could do nothing but obey.

She fell in with the mud-splattered riflemen of the 4th platoon and hoped for the best. The men seemed friendly enough. One or two of them nodded at her, apparently pleased to have a woman in the ranks, though most were indifferent. Her main perception, other than anxiety, was the smell of unwashed male bodies.

The march in the predawn light wasn’t long, and by full daylight they were within sight of Ostrov. The four tanks and six mobile guns assumed attack formation, and the infantrymen marched behind them in two lines. Mia’s slowly improving vision had a setback from the dust burning her eyes, though maintaining a permanent squint brought some relief.

The armored vehicles began to fire shells at the enemy positions, and Mia realized she was about to experience her first battle. Curiously, she wasn’t afraid, though perhaps it was because they were on the attack. If any men fell, their cries of pain, if they uttered them, were drowned out by the sounds of the shelling and the “uuurrrahh” that swelled up from the charging soldiers.

It was a heady experience running amidst the charging soldiers, and for a moment she felt invincible. It almost seemed the Germans were holding fire.

When tanks came within a few hundred yards of the first houses, she saw she was right. The Germans had simply waited until they were within range. Now they opened fire and men fell on all sides of her. Fear invaded her, and she tried to stay behind the tank. But others had the same idea, and as they pressed in for cover, they nudged her sideways into the open again. She fired wildly as she ran, with no idea of whether she hit anything useful.

Then they reached the first houses, and the tanks pushed into the streets. One of the men threw a hand grenade and blasted the interior of the first building. She was jogging now, as close behind the tank as possible.

A figure in green in a doorway shot at them, hitting the man next to her. In spontaneous fury, she fired back and the German collapsed. She hardly had time to grasp she’d killed a man when the comrades behind her lobbed grenades into each of the houses they passed, eliminating fire on their flank.

The rest of the battle was a blur. She shot at anything green that moved and at least twice managed to insert a new clip on the run and carry on. The detonation of the tank shells, the popping of rifle fire, the shouts and screams of the men all became a sort of white noise, and her mind focused on a single task, to run and shoot until someone ordered her to stop.

The order came late in the afternoon, when the return fire ceased and the captain reappeared, ordering them to the town square.

With men and light artillery guarding all the entrances to the square, Mia’s platoon and several others lined up. A lieutenant appeared, who sent scouting teams and sappers to examine all the buildings around the square, and by nightfall, they were cleared of mines. It was now safe to allocate quarters for the night.

Mia found herself in one of the grenade-blasted shops, a bakery, it seemed, though the few bits of bread they found were all charred. She dropped down alongside a group of men she didn’t know, took a long pull from her canteen, and opened her provender sack to eat the field rations she’d been issued the night before.

She was spent, but as Commissar Semenova passed by she struggled to her feet. “Comrade Captain, how can I find the snipers of the 109th,” she asked.

“You mean the women? They’re across the square.”

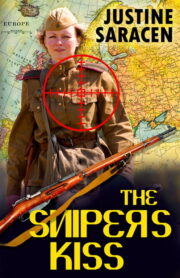

"The Sniper’s Kiss" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss" друзьям в соцсетях.