“No need for that, Miss Kramer. The embassy car arrived some time ago, just before I did. I explained to the chauffeur that for this trip, you were under my protection and that I would see to your safe return. My car is waiting to take you to Spaso House.”

“Ah, I see,” she said, nonplussed, and followed him through the station to the street outside. It was only eight in the evening, and not yet dark, but the heavy skies had blocked sunlight all day, and the early evening atmosphere was morose.

Nazarov joined her in the backseat of the car and turned amiably toward her. “I hope you found your journey worthwhile. Did the workings of the Tula factory meet your expectations? It’s one of our more important recipients of military hardware, so we are most anxious to see they are supplied adequately.”

“Yes, it seemed so. The foreman made it clear that the parts are delivered on time and in the right quantity. Obviously, that would be critical, since a single deficiency would disrupt the whole manufacture, and the Kremlin would be involved.”

“Yes, quite so. I’m pleased you were satisfied that we’re doing our best to move the American goods along. The gaps you believe to have found are most likely bad bookkeeping at the depots in Arkhangelsk and Murmansk.”

“Yes, that’s possible. In any case, thank you for your assistance. I’ll put that in my report to Mr. Hopkins.”

Upon reaching the embassy, she shook his hand once again and hurried through the dark back into what passed for American territory.

The next morning, before breakfast, she composed the text of her cable to Harry Hopkins.

Met w Ustinov and Nazarov stop even cajoled inspection of Tula arms plant stop workers malnourished canteen not receiving shipments stop mechanical materials and parts arriving but not food and possibly clothing stop workers are in rags stop theft somewhere betw Ustinov and factory presumably to divert to black market stop not sure who to inform stop anyone in the delivery train could be guilty stop please advise soonest full stop.

The wording seemed a bit strong. Maybe she should check with Ambassador Harriman before going on record. He’d already warned her to tread lightly.

She slid the draft to the side and realized she was hungry. All she’d gotten the night before was a quick sandwich from the embassy kitchen. A hot breakfast would do her good, and it would give her the opportunity to catch Harriman before he disappeared into his office.

As she emerged from her room into the corridor, she passed the cleaning lady, a woman whose name she didn’t know. “Good morning,” she said in passing, and let her mind drift to the thought of a cup of the embassy coffee.

“No, you can’t make direct accusations,” Harriman said. “Pilfering at that level is a major offense, and people are executed for less. I suggest you simply report what you saw, and what people said to you, and leave it to Hopkins or the White House to decide what action to take.”

Mia shrugged. “That seems to defeat the purpose of my coming, but I’ll do what you suggest. So what should I report to Molotov? He’s the one who’s always complaining about being cheated.”

“But he’s not complaining about problems at the Tula factory, is he? It was for a wide range of things that he was demanding double delivery. Missing Spam from the Tula plant was not one of his concerns.”

“But it should be one of his concerns. The Tula plant makes sniper rifles, among other things. If the workers are malnourished, they can’t be expected to produce precision weapons. Depriving them of food amounts to sabotage.”

“Perhaps so, but that’s not for you to judge.”

“It’s frustrating. This is the first theft I’ve been able to track down and have hard evidence for. The signed manifesto from the depot shows the food was shipped out. Leather, too, incidentally, for the shoulder straps, though the ones I saw were cotton. I’ve got to start someplace and show Molotov we’re taking his complaints seriously.”

“I see your point. So, why don’t you tell him verbally that the food shipment seems to have been diverted? He’ll have something to go on, assuming he wants to ‘go’ there at all, but you won’t incriminate anyone.”

“What about Hopkins? I’d like to clearly state my suspicions to him, at least. I wrote a telegram this morning that… well… named names. Cables from the embassy are secret, aren’t they?”

Harriman nodded. “Yes, once we transcribe them into code. Otherwise, I suggest you continue to gather your information without treading on toes, and then report verbally to the relevant parties. Do not leave a paper trail.”

“Yes, I suppose you’re right.” She reached for the marmalade, but it had lost its taste.

As if things could not get any worse, Molotov was not even available. At the Commissariat of Foreign Affairs, his secretary announced the foreign minister was in a meeting with Marshal Stalin and had no opening during the rest of the day. Would she like to request an appointment for the next morning?

Resigned, Mia agreed. Yes, she would. In the meantime, perhaps the foreign minister might want to read her report. She handed over the slender envelope with her observations, expressed as objectively as possible, letting him draw his own conclusions.

Then she left the commissariat at a lingering pace, stopping at the Spasskaya Tower before wandering over to the corner where Robert had agreed to pick her up in two hours. What could she do in the meantime?

She hadn’t waited for more than two minutes when a GAZ-Ford limousine pulled up in front of her, and two bulky men in uniform leapt out. As they came toward her from two directions she realized, from the color on their caps, they were NKVD police. The smaller of the two laid one hand on his holster and said, “Please come with us.”

Chapter Thirteen

April 1944

Alexia clambered down from the train at Novgorod. Since the Germans had been expelled in January, the station was in full operation, transporting troops to reinforce the follow-on offensive against the German army north. On this day, it received the 109th Rifle Division under the command of Major Bershansky, along with its separate sniper unit of twenty-four women.

The euphoria of the January liberation of Leningrad had subsided, and the Soviet troops found themselves in a hard struggle pushing the Wehrmacht westward. The addition of the 109th Rifle Division, including its snipers, was to add reinforcement to the slowing advance.

“These are our quarters?” Sasha glanced around at the cracked plaster and broken windows of the room they would bivouac in for the night. The remains of a blackboard on one wall revealed it had been a classroom, and Alexia felt a twinge of sorrow thinking about the school she had taught in and seen destroyed in Arkhangelsk.

“At least they’re going to feed us,” Alexia said, pointing with her chin toward a field kitchen just outside the school. A soldier fed wood into the small stove at the center while smoke rose from the chimney. The copper kettles on both sides already gave off steam, so it was clear the meal was ready to be served. By the aroma that drifted toward them, she could tell it was borscht.

In fact, they had just unloaded their packs against the wall when Major Bershansky arrived and ordered a lineup. They snatched their mess tins from their packs and ran to join the others. The cook, a grizzled, portly fellow, obviously had drawn some advantage from his proximity to food. He whistled softly as he ladled out the beet stew and twinkled at the line of women who held out their tins.

A few minutes later, they sat on their bedrolls with the steaming stew and a thick slice of larded black bread. Hardly had they finished their portions when the cook passed by the women’s corner with a canister of remaining stew.

“They told me you’re all snipers, so I wanted to make sure we take good care of you.” He ladled the canister’s contents into the tins held out to him.

“Thank you, Cook. But you’ve got a lot of mouths to feed tonight.”

“That’s a good thing. Lots of mouths means lots of soldiers.” He squatted down next to them, his captive audience. “We cooks can always tell how the army’s doing, even if the officers don’t tell you nothing. We know the casualty number same as the medics. Coupla times the field kitchen behind the line cooked up a hot dinner for some thirty men, but when the battle ended, no one made it back. All dead or wounded. We’d cooked all that food for no one.”

He glanced around, perhaps realizing that this was defeatist talk that could land him in prison. But when Commander Bershansky stood in the doorway, he seemed not to hear it and ordered everyone into the central courtyard of the school.

A microphone and speaker had been set up on a small platform at one end of the yard, and anticipating the usual political speech, Alexia and her friends lingered toward the back.

She was surprised, however, when a woman came to stand by Major Bershansky, and he announced, “Hero of the Soviet Union, Major Lyudmila Pavlichenko, has a few words to say to you.”

The troops cheered, for every man and woman in the Red Army knew her from The Red Star articles, and Alexia cursed herself for not moving closer to the front of the group.

The hero sniper began to speak. “I have just returned from a tour in the United States, as the guest of President and Mrs. Roosevelt, and I did nothing but boast about the courage and determination of the Red Army. I know you will continue to prove these boasts true.”

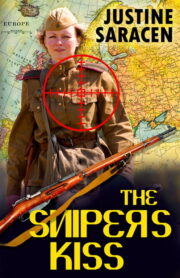

"The Sniper’s Kiss" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss" друзьям в соцсетях.