Mia stared at her, stunned. “You’ve come here to blackmail me. Is that it? If I don’t pay you two thousand dollars, you’ll get me fired.”

“Actually, I was thinking more of the president than of you. Mr. Roosevelt is campaigning for reelection. This kind of slander about his staff whispered to the conservative newspapers would be very embarrassing.”

Mia was paralyzed with outrage. Bad enough to have her own career ruined, but to compromise President Roosevelt… She suddenly felt nauseous.

“You have to give me time,” she said, beaten. “I simply don’t have two thousand dollars. I’ll need a few days to figure out how to get it.”

“You have lots of rich friends here in your new life, so I’m sure you can borrow it. I’ll give you until Saturday. After that, I’m going to The New York Times.”

Chapter Eleven

January 8, 1944

Alexia leaned against the wall of the oven that heated her barracks room, pressing as much of her back as possible against the tiles. The tall ceramic ovens were fueled only in the evenings, when most of the guard came off duty, and now, just before supper, she savored the first firing. She let her mind drift into pleasurable thoughts, the sound of chanting in Old Slavonic, the smell of incense, and the kiss of an American woman.

“What are you smiling about?” her comrade Olga asked.

Alexia was startled out of her reverie. “Oh, just enjoying the warmth. If only I could get it to spread down to my feet.”

“Take off your boots and heat your footcloths,” Olga advised. “You’ll have warm feet at dinner.”

“Even better with clean ones.” Alexia strode to her locker, took her last clean footcloths, and marched back to the oven. Draping them over her back, she flattened herself once again against the oven wall. The fresh fire warmed deliciously, and after only a few minutes, she was able to wrap her feet in the heated cloths. Sliding her boots back on, she sighed with pleasure.

She stood up to join the other women hurrying toward the mess hall when a young private stopped her. “Major Vlasik orders you to report to him. Right now.”

Frowning in a mix of anxiety and annoyance at missing dinner, she followed him back down the corridor to the commander’s office.

Vlasik sat relaxed, his arms crossed, but she saluted and stood at attention until his “At ease” order.

“Two things,” he began, as if to prepare her for a list. “Your escorting of the American diplomats was satisfactory. I have already commended Lieutenant Yegorov. However…”

Alexia’s lips tightened. She hated the word “however.”

“I understand that you accompanied Miss Kramer to church services.”

“Yes, sir. It was Christmas morning, sir. She explained she was raised Orthodox and requested to see such a service.”

“Do you not appreciate how inappropriate that was for a member of the Kremlin regiment?”

“Yes, sir. But I assumed I was obliged to grant her request, since she was Marshal Stalin’s personal guest.”

“‘Personal guest’ is an exaggeration. She was the secretary to a White House emissary. If she attended a dinner with Comrade Stalin, it was as an interpreter.”

“Yes, sir. But Metropolitan Sergei has expressly allied the Church with the nation in defense of the motherland, so I thought it would not be offensive on this one occasion—”

“It is not your place to make such judgments. But I will let it pass this once.”

Alexia was too much of a soldier to reveal her feelings and remained neutral. “Thank you, sir. But you said ‘two things,’ sir. What was the other one?”

“Your dissatisfaction. I understand you feel your role as Kremlin guard is a way to avoid active service. Perhaps you think we are a regiment of cowards.”

Alexia was momentarily speechless. How could he have known her thoughts? She had not fully resolved the issue in her head, so how could she explain it to him?

“Not at all, sir. I am very satisfied, in fact, deeply honored, to serve in this way. At the same time, I think of my brothers and sisters at the front who offer their bodies in the defense of the motherland and wonder sometimes if I don’t have a moral obligation to do the same.”

He closed his eyes for a moment, as if in paternal concern. “Alexia,” he said, and it was the first time he’d ever called her by her first name.

“Am I in trouble, sir?”

“You should be. If anyone else were sitting here, you would be. But I know you’re a patriot and a good party member. If you don’t want to continue in the Kremlin regiment, we have hundreds of qualified recruits who will happily take your spot. You must think seriously about this.”

His reaction was unexpected. She had not yet decided, but now a decision was thrust upon her. If she stayed, she would be guarding and ceremonially marching until her retirement from the service. Father Zosima would certainly approve, but her conscience would not.

She took a breath. “I would like to serve at the front, sir.” There, she’d crossed the line.

He drummed his fingers on his desk. Was it in impatience at her naïveté? “In what capacity? Medical? Communications? If you do not request specific training, the army will assign you to cooking or laundry. I don’t think that’s what you had in mind.”

“I… um… well, during training, I was superior in marksmanship.”

“I see. Well, the army always needs marksmen, it’s true.” He sat up, terminating the interview. “All right. I will recommend you for sniper school. You are dismissed.”

Stunned at how quickly it all went, she snapped to attention and saluted. “Yes, sir, Comrade Major!”

Duties at the Central Woman’s School of Sniper Training in Podolsk were decidedly less glamorous than those of a Kremlin guard.

The barracks, built only months before by the women themselves, were basic and, in the January weather, even colder than her quarters in the Kremlin. And the call to duty was even more rigid. Each morning, she had five minutes to wash, dress, and fall into line before the mess hall.

Breakfast—of black bread, sausage, and tea—had to be collected, consumed, and cleaned up within twenty minutes. The recruits were still strangers, all afraid to speak, so the main sound in the mess hall was the clank of the metal mess kits.

At seven o’clock, the recruits fast-marched to the quartermaster, where they lined up to receive their uniforms. Alosha’s gymnasterka was simpler than her guard’s tunic and had collar tabs with an enamel and brass insignia of crossed rifles over a target. Her breeches hung on her, but their bagginess was useful for kneeling and squatting, which she’d never done as a guard. The bottoms tucked into boots of imitation leather, though for winter training on icy ground, she was also issued the dense felt valenki.

At eight o’clock they filed into a small auditorium for political instruction, ensuring they were all motivated by the highest communist principles. Alexia glanced discreetly at the other women, wondering if they were as bored as she was listening to the principles that she’d heard reiterated endless times since joining the Komsomol.

Nine o’clock brought them to the gymnasium, where they were lined up in two squads, each with four rows of five women abreast. “You will memorize your place in the lineup,” the sergeant ordered, and Alexia noted that she was the second woman in the second row in the second squad. That was convenient.

“The rules for discipline and for service of the garrison are posted in each barracks, and you will learn them by heart tonight.”

The next order was to drop to the floor for calisthenics, which proved more rigorous than she expected. At the end of the hour, she stood in place once again, dry-mouthed and panting. But if that was the worst they had to throw at her, she’d do fine.

The women stood in formation for several minutes, watching the platform at the front. Finally, a door opened and the major emerged, a large robust man with a Cossack mustache.

The fifty recruits came to attention. This, they all knew, was Major Kulikov, who had fought alongside the famous Vassily Zaitsev at Stalingrad. The two associations, Zaitsev and Stalingrad, gave him an aura of greatness.

Two men came directly behind him wheeling a long cart. “At ease,” Kulikov said, and at his signal, one of the men opened the cart lid and lifted out a rifle. An unmistakable murmur of approval rippled through the ranks.

The men handed rifles in armloads of five to the woman at the end of each row, and she passed them along until each recruit held one. Alexia hefted hers. It was longer but a bit lighter than the ceremonial rifle she’d held at the Kremlin. She was used to rifles, but obviously most of her classmates were not.

Major Kulikov laid his fists on his hips and shook his head. “Look at you,” he snorted. “You’re cradling those things like babies. They are deadly weapons, which you are going to use to kill people. When in tight formation, hold them upright and vertical, at your right shoulder. When in the field, grasp them like this.” He held one diagonally in front of him, one hand midway up the barrel and the other around the stock with the index finger flat against, though not around, the trigger.

“This is the Mosin Model 1891 / 30, your friend and savior. You will always know how many rounds are in the clip and how many clips are left on your bandolier. You will know every part of your rifle and keep it spotlessly clean and oiled. To do so, you will disassemble it in this manner, using the bayonet as a screwdriver.”

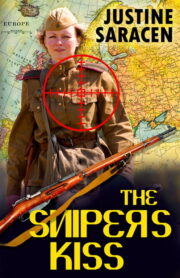

"The Sniper’s Kiss" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss" друзьям в соцсетях.