“Yes, ma’am?”

“But we need someone who speaks Russian, and the president is loath to use his official interpreter.”

“I’ll be happy to help, but who is the guest?” Mia imagined one of the pasty men she’d met in Moscow and wondered if this one too would travel with a sausage and a pistol.

“Major Lyudmila Pavlichenko. A female sniper who has just received the Hero of the Soviet Union medal and whom the Kremlin is quite keen for the West to meet.”

“Oh, that sounds intriguing. When does she arrive?”

The First Lady clasped her hands, her gesture of satisfaction. “Tomorrow afternoon. I shall ask Mr. Hopkins to give you the day off to join the welcoming committee.”

According to the printed biography forwarded by the Soviet Press Department, Lyudmila Pavlichenko was twenty-five years old and already a major. A photo that had come with the press material showed a dark-haired woman with a simple, open face and slightly heavy brows, in a three-quarter pose. She held a rifle across her chest, of which only the scope and the bolt handle were visible. What stood out was her atrociously cut hair, for a large, straight tuft of it jutted out from under her field cap as if it had been blunt cut in a hurry with a bayonet.

When she arrived at the White House, President and Mrs. Roosevelt met her at the entrance while Mia acted as interpreter. After certain pleasantries, the Roosevelts invited their guest to luncheon along with the Russian ambassador and his wife, and while the group ate chicken à la king, Mia had a chance to study her.

She looked older than her years, though at certain angles she was attractive in a matronly sort of way. When she removed her enormous officer’s cap, she revealed a slightly tidier though still uninspired haircut, but her eyes seemed kind, and the fact that she had no feminine vanity was in its way appealing. Most importantly, she spoke intelligently, a welcome but unnecessary skill for a sniper. She was also adept at concealing what surely must have been shock at seeing the president of the United States in a wheelchair.

“You must be glad to get away from the battlefield,” Eleanor said, cutting her chicken into tiny pieces that needed only a few nibbles before they could be swallowed.

Pavlichenko ingested the big chunks with no reservation and wiped her mouth. “I hate to leave my colleagues in the struggle, but my visit here was also a military duty.”

“Where were you engaged for the most part?” Roosevelt asked.

“In the Crimea, defending Sebastopol,” she said with obvious pride.

The president frowned slightly with paternal concern. “Where you ever wounded? It seems so much more terrible for a young woman.”

Pavlichenko straightened slightly. “Twice, in fact. Shrapnel wounds from shells exploding close by. Sometimes the Fritzes would put up so much noise blasting away at me, it was a real concert. Bullets whistling over me and hitting all around me.” She swept her fork in imaginary trajectories past her head. “Wounded or not, all I could do was stay down and not move for three hours.”

“How dreadful for you,” Eleanor exclaimed, with polite horror.

The luncheon conversation continued in such fashion for an hour, and at its conclusion, the president announced, “Miss Kramer will take you on a brief tour around the White House. After that, the press will arrive for some photographs, and then at four, we’ll have a reception. Miss Kramer, would you also be so kind as to escort Major Pavlichenko to her hotel after the reception?”

“I’ll be happy to,” Mia replied, pleased to be away from her cubicle for a couple of hours.

While President and Mrs. Roosevelt returned to their duties, Mia guided the guest through the main staterooms, explaining what little she knew about their functions. As they strolled, Mia noted that Pavlichenko was slightly plump, as a woman would be who simply did not care about her appearance. Her indifference to style was also evident in the way she wore her uniform. The man’s tunic, amply decorated with medals, was cinched with a Sam Browne belt high over her rounded hips and directly under her breasts. She wore a skirt that hung in a formless column to mid-calf over leather boots.

“I understand you were in Moscow,” Pavlichenko said as they left the last of the staterooms.

“Yes, in January. Bitter cold, of course, but I got to see the Grand Kremlin Palace. I was tremendously impressed, as you can imagine.”

“Yes, it is impressive. But the tsars built their palaces on the blood and toil of the people.”

Their arrival at the press conference removed the need for Mia to reply to such cynicism. A butler stepped in front of them and opened the door to a room full of reporters. Camera bulbs flashed and shutters clicked as they entered and took seats behind a lectern.

Eleanor Roosevelt spoke first, lauding the courage and forbearance of the female Russian soldiers and the importance of the alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union in fighting for freedom.

“We have American women in all branches of our military service, I am pleased to say. WACs, WAVEs, air force service pilots called WASPs, and women serve even in the marines and coast guard. We can be proud of these, our sisters, wives, and daughters, but we cannot say, and I dearly hope we never have to say, that our women give their lives in the trenches.”

Polite applause followed the mention of patriotic women.

“However, it has been the fate of the Soviet Union to be invaded by a ruthless foreign force, and thus it has mobilized all its citizenry, its women, too, even on the front lines. I am honored to present one of their bravest…” She paused dramatically. “And most deadly. Major Lyudmila Pavlichenko, you have the floor.”

Mia repeated the First Lady’s introduction in Russian, for the major’s benefit, and during the renewed applause, Pavlichenko strode to the podium.

Obviously unaccustomed to public speaking, she unfolded a piece of paper and addressed the room of reporters haltingly. After a few remarks about the kindness of the Americans to receive her, and her hopes that the Americans would soon join the European struggle, she simply asked for questions.

“How many men have you killed?” some young reporter shouted from the rear.

Pavlichenko seemed unfazed by the crudeness of the question. “Over three hundred.”

“Did you miss shampoo and pretty dresses and makeup on the front?” another called out.

“Some of my comrades do. Perhaps the way you would miss your shiny shoes and neckties and clean white shirts.”

“Do romances happen on the battlefield?” A few reporters snickered.

Pavlichenko exhaled in obvious exasperation. “In blood and filth and snow, with comrades dying or mutilated every day under fire and bombardment? Rarely.”

The questions continued in the same trivial vein until Pavlichenko lost patience. She leaned forward with her elbows on the podium and seemed to stare at those in the back row. “Gentlemen, millions… millions… of Soviets have died defending their homeland, while only a few thousand Americans have fallen in North Africa, Italy, and the Pacific. No one has come to our aid on the Eastern Front. I am twenty-five years old, and I have already killed 309 invaders. Do you not think, gentlemen, that you have been hiding behind my back for too long?”

After a moment of stunned silence, the reporters applauded.

The reception was both pleasant and tedious. It was another occasion to eat festive food a cut above what the White House cafeteria usually served, but tedious because the people that came along the reception line to greet the guest asked the same dreary questions again and again. How did she like the United States? How did she like American food? How did she like American clothes, cars, jazz, and all things American? Pavlichenko’s answers became briefer and briefer.

When the last person passed them, Lyudmila broke away to chat a bit with Eleanor Roosevelt and Harriman, who spoke enough Russian to act as interpreter. Mia relaxed where she stood, sipping her fruit juice.

A reporter sidled up next to her. “I wonder if they all look like that,” he muttered.

“What do you mean?” Mia was sure she knew but wanted him to say it.

“Well, frankly, she’s a little frumpy, don’t you think? Not like our women.”

Mia felt her cheeks redden. Without facing him, she asked with forced neutrality, “You think so?”

“Well, it’s obvious, isn’t it? I mean, what kind of fellow would want to romance someone who shot people and looked like that?” She could hear now the slight slur in his words that suggested he’d drunk too much White House wine.

He went on with his theory of femininity. “They make a good pair, don’t they, the sharpshooter and the president’s wife. Two homely women who found another way to advance themselves in a man’s world.”

Mia turned slowly toward him and hoped her contempt was as obvious on her face as in her words.

“You may be judging all women by what you feel in your groin, but not all women care about your sexual approval. One of those ‘frumpy’ women has published more than you and has influence on the domestic policy of your country. The other one, in case you hadn’t heard, has personally felled, with a single shot, over three hundred better men than you. So I think this would be a good time to shut your pie hole.”

She turned her back on him and wandered over to where Pavlichenko was in conversation with the president and Harriman.

“Thank you for agreeing to this tour, Miss Pavlichenko,” the president said, looking up at her from his wheelchair. “Unlike in your own country, a good many Americans are unwilling to fight for Europe. Even the attack on Pearl Harbor has not convinced them that this is a global war. I am hoping your courage will set an example.”

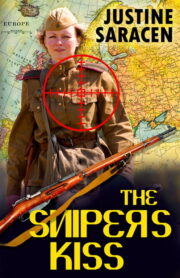

"The Sniper’s Kiss" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sniper’s Kiss" друзьям в соцсетях.