His daughter. Could it be true that he had a daughter?

“My ship leaves in two days.” Sabine pulled a slip of paper out of her sleeve and handed it to him. “Meet me at this address at dawn, and I’ll take you to her.”

Alex heard the rustle of Sabine’s silk skirts as she walked to the door, but he did not look up from the folded paper clenched in his hand.

“One last thing, Alexander,” she said. “Albany intends to have you arrested as soon as D’Arcy leaves the city.”

CHAPTER 21

Skrit scrit, scrit. Claire drew her feet in as the mouse crossed the floor. It was bigger and bolder than the mice in the fields at home.

The old woman had not brought food yet today, so she and her doll were hungry. Poor Marie was dirty as well. If Grandmère was here, she would scold Claire for not taking better care of her doll. Grandpère had made Marie specially for his little girl from straw and rope, and then Grandmère had sewn her pretty gown from scraps.

The girl pressed her nose against Marie’s soft belly and sniffed, but the smell of Grandmère and Grandpère had been gone for a long, long time.

CHAPTER 22

When Glynis came down for supper, a man dressed in a priest’s robes was already sitting at the head of the table. He looked at her with gray eyes that were the same color and shape as her own, but they were as cold as a frozen pond.

“She does look like our former sister,” the priest said in a flat tone.

“Ye are my uncle?” Glynis asked.

After growing up in a family in which she looked like no one else, Glynis had been disappointed to see no resemblance between herself and her aunt. She could see herself in this tall, gaunt priest—but she did not like what she saw.

“Yes, I am Father Thomas,” he said, as if being himself was a great responsibility. “You may sit.”

Glynis’s backside was barely on the bench before her uncle started the prayer. He recited it rapidly with no inflection, giving Glynis the impression that his mind was elsewhere. When he finished the prayer, he helped himself to the choicest piece of meat on the tray and began eating before the rest of them had any.

“I hope you have a more obedient nature than your mother did,” he said, looking at her with a grim expression. “I pray you will not bring more shame upon our family.”

He did not expect an answer, and Glynis had to bite her tongue to prevent herself from giving him one he was sure not to like.

Glynis’s lively aunt Peg and Henry seemed to wilt in the priest’s presence, and the supper conversation was stilted. Midway through the meal, the priest put away his eating knife.

“Gavin Douglas has been imprisoned,” he announced.

Aunt Peg gasped, and Henry went pale.

“How can that be?” Henry asked. “He was supposed to become the Archbishop of St. Andrews.”

“The queen nominated him, and she is no longer regent,” Father Thomas hissed. “Now the Douglases are out of favor.”

“What does this mean?” Peg asked in a hesitant voice.

“It means, dear sister,” Father Thomas said, turning his venomous eyes on her, “that I will not be going to St. Andrews with Gavin Douglas.”

Glynis was tempted to suggest that Father Thomas should be grateful he was not following this Gavin Douglas to prison.

“What in the name of God possessed Gavin to advise his nephew to marry the queen?” Father Thomas raised his hands as he spoke, as if beseeching Heaven. “As her lover, Archibald Douglas had the queen in his pocket. And the council could do nothing because the king’s will provided that the queen should be regent so long as she did not remarry.”

Glynis dropped her gaze to the food growing cold in front of her.

“Damn him to hell,” Father Thomas said. “Gavin should have stuck to his poetry.”

“He is a poet?” Glynis asked, hoping to divert Father Thomas to a topic less upsetting to him.

“Gavin Douglas is famous for his own poetry as well as for his translations of ancient poems,” Father Thomas said. “A useless activity, of course, but one that would not have cost him a bishopric.”

“Useless?” Glynis said. “We Highlanders hold our poets in high esteem.”

From the way Father Thomas’s eyebrows shot up, he was not accustomed to disagreement.

“Why has the poor man been imprisoned?” Glynis asked, her curiosity overtaking her caution, as it often did.

“He is accused of attempting to buy the bishopric from the Pope.” Father Thomas shrugged one bony shoulder. “If Albany’s faction did not suspect Gavin had also advised the queen to flee to England with the Scottish heir, no one would care if he bought it.”

Glynis cleared her throat. “Are ye aware, Uncle, of what this new regent’s attitude is toward the Highland clans?”

“Of course I am,” he snapped. “’Tis fortunate that you escaped that God-forsaken place, for Albany has given the Campbells the crown’s blessing to destroy this Highland rebellion ‘by sword and by fire.’”

Glynis put her hand to her throat, fearing for her family back home. “What does that mean?”

“It means they have a free hand to lay waste to the rebels’ lands and murder anyone who stands in their way, including women and children,” Father Thomas said, “When the rebels submit, as they will, the Campbells are to collect the rebel chieftains’ eldest sons as hostages to assure their father’s good behavior.”

“My brother is only four years old.” Glynis felt sick to her stomach.

“Then it may just be possible to teach him civilized ways.”

If her father knew of this plan, surely he would see sense and leave the rebellion. Before Glynis could question Father Thomas further, he got to his feet.

“I must pursue my advancement independent of Gavin Douglas now,” he said, fixing his hard gaze on Henry. “It will be costly.”

Father Thomas did not wait for a response. Without so much as a fare-thee-well, he left the room with long-legged strides.

“Thomas is an important man in the church,” Peg said when he had gone, as if that should excuse his rudeness.

“Eat up,” Henry said to Glynis, as he stuffed an apple tart in his mouth. “A man likes a woman with some flesh on her bones.”

Glynis could not recover her good humor as quickly as her Aunt Peg and Henry, but she managed a weak smile and took a bite. The apples were not as tart as at home. Nothing tasted good here.

“What do ye think about James the Baker?” Henry said, looking at her aunt. “He’s a fine man. Wouldn’t he make our bonny niece a good husband?”

Glynis choked on the bite of dry tart caught in her throat. “Thank ye for your concern,” she said when she could speak, “but I don’t wish to marry again.”

“Don’t wish to marry?” Henry said, then repeated it more loudly: “Don’t wish to marry?”

When Glynis shook her head, Henry and her aunt exchanged startled glances.

“James is a steady man with a good future before him.” Her aunt reached across the narrow table and patted her hand. “It can’t hurt to meet him.”

“Thank ye kindly,” Glynis said. “But meeting the man will no change my mind.”

Bessie came in then and stooped to speak to Henry in a low voice.

“James is here,” Henry said, and gave Glynis a wide smile. “Make yourself pretty while I fetch him.”

Two hours later, Glynis was so bored she wanted to stab herself in the eye. James was easily the most tedious man she had met in her life. Alas, he was unattractive as well.

“Do ye never leave the city?” she asked after listening to him drone on about meetings of his guild. “Surely ye must long to take a sail or a walk in the meadows now and again?”

“There are pirates roaming the seas!” Poor James looked genuinely alarmed. “Besides, the sea makes me sick as a dog.”

The sea made him ill?

A wave of homesickness swept over Glynis, leaving a sense of hopelessness in its wake. She had always lived on the sea and had no notion how much she would miss it. Even when she was married to that despicable Magnus, she could hear the sea from her window and walk on the shore every day.

Glynis’s attention was brought back to the present by the sudden damp heat of a heavy hand on her thigh.

“Ye are a pretty thing,” James said, leaning close enough for her to see the spittle on his chin. “And I believe I’m just the man to tame a wild Highland lass.”

CHAPTER 23

Alex walked the city streets in the bleak hours before dawn. Occasionally, women of the night called out to him from doorways. No one else was out at this hour save for thieves and groups of drunken young men looking for a fight. But with his claymore strapped to his back and dirks hanging from his belt in plain sight, no one gave Alex trouble.

After tossing and turning on the too-small bed at the tavern, Alex had given up on sleep. He wished he could talk with Glynis about the problem of this wee girl Sabine claimed was his daughter. Glynis would give him honest advice. But he could not very well wake up her relatives’ household by pounding on their door in the middle of the night.

When the first streaks of dawn speared through the sky, he unfolded the paper that Sabine had given him and read the directions written there. What in the hell was wrong with Sabine keeping the child in the most wretched part of the city?

Alex turned down a close and held his plaid over his mouth and nose as he walked farther and farther down the hill. He was nearly to the sewage-filled loch before he finally reached the place. He pounded on the door with murder running through his veins.

A woman opened the door just wide enough for him to see her greasy hair and careworn face. Her eyes grew wide as she took him in.

“Alexander MacDonald?” she asked in a hoarse voice.

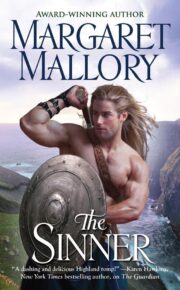

"The Sinner" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Sinner". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Sinner" друзьям в соцсетях.