This was his church. The castle would have its own chapel, I supposed, so the Comte would never come here. He would be quite different from my grandfather; if his flippant conversation was an indication of his beliefs he was certainly not devout.

I came out into the fresh air and made my way to the graveyard.

Ornate statuary had been placed over many of the graves. There were angels in plenty and figures of the saints. Some of them were so large and lifelike that one almost expected them to speak.

I did not think my mother would be among those with the elaborate sculptures, but there among the most magnificent were the burial grounds of my ancestors. The name St. Allengere was on many of the headstones. I went to the most ornate of them all. Marthe St. Allengere; wife of Alphonse 1822-1850. So that was my grandmother. She had been young to die. I daresay childbearing and life with Alphonse had taken their toll. I walked on and found the grave of Heloise. There was no elaborate statue there. It was an inconspicuous little grave, but all the plants on it had been well tended. There was a white urn from which grew pale pink roses. Poor Heloise! I wondered about her. How she must have suffered. I thought of the Comte. Of course he may not have been the man involved with the tragic girl. I was being unfair to him to be so sure that he was he. I had no reason for doing so except that he was the man he was. Heloise was a beautiful girl, and I knew that he would take great delight in seducing the daughter of the enemy house.

I passed on. It was some time before I found my mother’s grave. It was in a corner among those of the less flamboyantly decorated. It just said her name, Marie Louise Cleremont. Died aged 17. I felt an intense emotion sweep over me and I saw the rose bush which had been planted there through a haze of tears.

Her story was not unsimilar to that of Heloise. But she had died naturally. I was glad she had not given up. I had robbed her of her life. Had she lived, we should all have been together, she, Grand’mere and I. Poor Heloise had been unable to face life. Hers was a different story although it had begun as my mother’s had with a lover who had failed her. A lesson to all frail women.

I turned away and started to make my way back to the church door where I had left Marron. In doing so I had to pass the St. Allengere section and I was startled to see a man standing by Heloise’s grave.

He said,’ ‘Good day,” and as I returned his greetings I could not resist pausing.

“A fine day,” he said. Then: “Have you lost your way?”

“No. I have just been having a look at the church. I left my horse tethered at the door.”

”It’s a fine old church, is it not?”

I agreed that it was.

”You are a stranger here.” He looked at me piercingly. Then he said: “I believe I know who you are. Are you staying by any chance at the vineyards?”

“Yes,” I told him.

“Then you are Henri’s daughter.”

I nodded, and he looked rather emotional.

“I heard you were there,” he said.

“You must be … my uncle.”

He nodded. “You are very like your mother… so like her, in fact, that for the moment I could believe that you were she.”

“My father said there was a resemblance.”

He looked down at the grave.

“Have you enjoyed your visit here?”

“Yes, very much.”

”It is a pity that it has to be as it is. And Madame Cleremont, she is well?”

”Yes, she is in London.”

“I have heard of the salon. I believe it prospers.”

“Yes, now we have a branch in Paris. I am going back there tomorrow.”

“I believe,” he went on, “that you are Madame Sallonger.”

“That is so.”

“I know the story, of course. You were brought up by the family and in due course married one of the sons of the house. Philip, I believe.”

“You are very knowledgeable about me. And you are right. I married Philip.”

“And you are now a widow.”

“Yes, I have been a widow for twelve years.”

The scarf which I was carrying had caught in a bramble. It was dragged from my hands. He retrieved it. It was silk, pale lavender, and similar to those we sold in the salon.

He felt its texture and looked at it intently.

“It is beautiful silk,” he said. He kept it in his hands. “Forgive me. I am very interested in silk naturally. It is our life here.”

“Yes, of course.”

He still kept the scarf. “This is the best of all silks. I believe it is called Sallon Silk.”

“That is true.”

“The texture is wonderful. There has never been a silk on the market to match it. I believe your husband discovered the process of producing it and making it the property of the English firm.”

“It is true that it was discovered by a Sallonger, but it was not Philip, my husband. It was his brother, Charles.”

My uncle stared at me incredulously.

“I was always of the opinion that it was your husband. Are you sure you were not mistaken?”

“Certainly I am not. I remember it well. We were amazed that Charles should have come up with the formula because he had always given the impression that he was by no means dedicated to the business. My husband was … absolutely. If anyone should have discovered Sallon Silk it should have been him. But it was most definitely Charles. I remember it so well. It was a brilliant discovery and we owe it to Charles.”

“Charles,” he repeated. “He is the head of the business now?”

“Yes. It was left to the two of them, and when my husband … died … Charles became the sole owner.”

He was silent. I noticed how pale he was and his hands shook as he handed me back the scarf.

He lifted his eyes to my face and said: “This is my daughter’s grave.”

I bowed my head in sympathy.

He went on: “It was a great grief to us all. She was a beautiful gentle girl… and she died.”

I wanted to comfort him because he seemed so stricken.

He smiled suddenly: “It has been interesting talking to you. I wish … that I could invite you to my home.”

I said: “I quite understand. And I have enjoyed meeting you.”

“And tomorrow you are leaving?”

“Yes. I am returning to Paris tomorrow.”

“Goodbye,” he said. “It has been most… revealing.”

He walked slowly away and I made my way back to Marron.

Our last evening was spent with Ursule and Louis in their little house on the Carsonne estate. It was a pleasant evening. Ursule said how she always looked forward to Henri’s visits and she hoped that now I had come once I would come again.

I told them how interesting it had all been. I mentioned to them that I had been to the graveyard to see my mother’s grave and had there met Rene. At first my father was taken aback but then he was reconciled.

“Poor Rene,” he said. “Sometimes I think he wishes he had had the courage to break away.”

“He is our father’s puppet,” replied Ursule rather fiercely. “He has done all that was expected of him and his reward will be the St. Allengere property in due course.”

“Unless,” said Louis, “he does something to earn the old man’s disapproval before he dies.”

“I am glad I chose freedom,” said Ursule.

Later they talked about the Comte.

“He’s a good employer,” said Louis. “He gives me a free hand and as long as I keep the Carsonne collection in order I can paint when I will. Occasionally he arranges for me to have an exhibition. I don’t know how we should have come through without his father and now him.”

“He does it all to spite our father,” said mine.

”The Comte has a fine appreciation of art,” said Louis. ‘ ‘He respects an artist and I think he is not unimpressed by my work. I owe him a great deal.”

“We both do,” said Ursule. “So Henri, do not speak harshly of him in our household.”

“I admit,” said my father, “that he has been of use to you. But his reputation in the neighbourhood …”

“That’s a family tradition,” insisted Ursule. “The Comtes of Carsonne have always been a lusty lot. At least he doesn’t assume the mask of piety like our own Papa … and think of the misery he has caused.”

“I daresay de la Tour has caused discomfort in some quarters.”

“Now, Henri, you are referring to Heloise and you don’t really know that he had anything to do with that.”

“It’s clear enough,” said my father. “He has been making himself agreeable to Lenore.”

“Then,” said Ursule to me, “perhaps you should beware.”

“Katie has formed a friendship with his son Raoul,” went on my father. “She has been over there today. He sent the carriage for her. I’d like to tell him to keep away.”

“Oh, you must be more diplomatic than that,” said Ursule. “In any case you with Lenore and Katie are leaving for Paris tomorrow, so you will all be out of harm’s way.”

I was interested to hear what they had to say about him. In fact, it is all I remember of that last evening with Ursule and Louis.

The next day we left for Paris.

The Countess was there. Grand’mere and Cassie were still in London.

“Why,” cried the Countess embracing me. “You look rejuvenated. What has happened to you?”

I found myself flushing.

“I enjoyed seeing the place,” I said.

“We went to the chateau,” Katie told her. “There was a falcon there and ever so many dogs … little puppies some of them. They have an oubliette which they push people into when they want to forget them for ever more.”

“I wish we had one here,” said the Countess. “Madame Delorme has brought the mauve velvet back. She says it is too tight. She could be the first one to go in, if I had my way.”

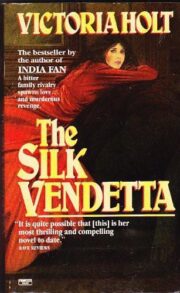

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.