He said: “What we must set about doing without delay is finding a house of our own for we shall be living in London a great deal.”

“Oh, that would be wonderful!”

“We should start looking right away. Houses are not all that easy to find and the search might take some time. I have one or two in mind which we could look at.”

How I enjoyed those days! We looked at several houses—none quite to our taste.

“We must find exactly what we want,” said Philip. “It must be somewhere near here.”

There was a tinge of sadness for me as I looked at houses. Our home. But I would think about Grand’mere … still living at The Silk House. I knew she would miss me terribly, for all my life we had been together. She had never mentioned this; nor had she shown any sadness at the prospect of our separation; her devotion was entirely selfless. She believed that my marriage to Philip was the best thing that could happen to me and she was content for that reason.

Philip was very susceptible to my moods. He had known that I disliked living under the same roof as Charles and understood why although I had never told him of that encounter before the episode with Drake which had made him so angry with me.

Houses were fascinating. I would wander round the empty rooms, imagining the people who had lived there and wondering what had happened to them and where they were now. We found one house—not very far from the river; it had eight rooms—two on each floor, so it was rather small for its height and a room had been added to the top floor, with a glass roof and very large windows. We were told that the house had belonged to an artist and this had been his studio.

“What a lovely room!” I cried. “It reminds me of Grand’mere’s at The Silk House.”

“It would be an ideal workroom,” said Philip. “It would suit her very well. And you see, there is a room adjoining which could be her bedroom.”

I turned and looked at him. “You mean that Grand’mere would come and live with us?”

“Well, that is what you want, isn’t it?”

“Oh Philip,” I cried, “you have made me so happy.”

“That is what I want.”

Then I told him of how I had been worrying about her. She would have been miserable in The Silk House without me.

“I know you well,” he replied, “so I knew what was on your mind.”

“You are so good to me.”

“It’s practical,” he said. “She can work there. It will be much more convenient than The Silk House.”

“I’ll tell her that. Oh Philip, I want to go back … now I can’t wait to tell her.”

What a happy homecoming that was! I think it made what happened afterwards the harder to bear.

The first thing I did was rush up to Grand’mere. She was in the workroom and had not heard our arrival.

“Grand’mere,” I cried, “where are you?” And then I was in her arms.

She studied my face and was aware of my happiness.

“Oh Grand’mere,” I said. “We’ve been house-hunting and we have found the very thing.”

Why does one want to withhold good news? Why did I not burst out with it? Perhaps one feels that by hesitation one gives it greater impact; perhaps one wants to prepare the other for complete enjoyment. She had given no hint of sadness although the fact that we had a home in London would, she must think, mean more separations for we should come only infrequently to The Silk House.

I could withhold it no longer. “What decided us was the room at the top. It is rather like this one. The roof is glass. The light is wonderful. It is the north light. It was designed by an artist so that he could work there. The first thing Philip said was: ‘This will be just right for Grand’mere.’ “

She looked at me in puzzlement.

“Are you pleased?” I asked.

She stammered: “But … you and Philip … will not want …”

“But we do want. I could never be completely happy away from you.”

“My child … mon amour …”

“It’s true, Grand’mere. We have been together all my life. I could not have any change now … just because I am married.”

“But you must not make these sacrifices.”

“Sacrifices! What do you mean? Philip is the most practical man where business is concerned. He talks business almost all the time. He thinks of little but business. And I am becoming the same. He said it will be easier if you are in London. It was always rather a nuisance sending those bales right down here. You are still in the hands of your slavedrivers … and you will have to work … and work … in that room with the north light.”

“Oh, Lenore,” she murmured and began to weep.

I looked at her in dismay. “This is a nice homecoming! Here you are in tears.”

“Tears of joy, my love,” she said. “Tears of joy.”

We had been home three days. What happened stands out in my memory as I hope nothing ever does again.

Philip and I had ridden out in the morning. The forest was beautiful in May. It was bluebell time and we constantly came across misty blue clumps of them under the trees.

As we rode along we talked excitedly about the house and how we would furnish it and how he hoped to find another material as successful as Sallon Silk.

He said: “It’s wonderful to be able to talk to you about all this, Lenore. Most women wouldn’t understand a thing.”

“Oh, I am Andre Cleremont’s granddaughter.”

”When I think how lucky I am …”

“I’m lucky, too.”

“We must be the luckiest people on Earth.”

What a joyous morning that was! It made what happened afterwards all the more incomprehensible.

Lady Sallonger joined us at luncheon. We had arranged that she should not be told about the house just yet. She would not want me to go. She seemed to think that now that I was her daughter-in-law she had an additional right to my services.

She was a little peevish because she had a headache. I suggested she go to her room instead of lying on the sofa in the drawing room. I would put some cotton wool soaked in eau de cologne on her forehead. She brightened up considerably; and when she went to her room I accompanied her.

I was with her quite a long time, for when I had ministered to her headache she wanted me to stay and talk until she slept; and it must have been almost an hour later when I was able to tiptoe out.

The house was very quiet. I went to our room expecting to find Philip impatiently waiting for me. He was not there. I was surprised for he had said something about our taking a walk together in the forest as soon as I was free of his mother.

There was a knock on my door. It was Cassie.

“So you’re alone,” she said. “Good. I wanted to talk to you. I hardly ever see you now. Soon you’ll be going to London and staying there. It’ll be your home … not this.”

“Cassie, you can come and stay with us whenever you want to.”

“Mama would protest. She is especially demanding when you are not here.”

“She is demanding when I am.”

“I am so glad you married Philip because it makes you my sister. But it does take you away.”

“A woman has to be with her husband, you know.”

“I know. I can’t imagine what it will be like when you stay all the time in London. What am I going to do? They won’t try to find a husband for me. They can’t even find one for Julia. So what chance would I have?”

“One never knows what is waiting for one.”

“I know what is waiting for me. Dancing attendance on Mama until I am old and just like her.”

“It wouldn’t be like that for you would never be like her.”

“Do you remember that time when we were all up in your grandmother’s room and we talked about having a shop together … making wonderful clothes and selling them? Wouldn’t that be lovely if we could take Emmeline, Lady Ingleby and the Duchess and all go off together? I used to dream we did and now you have married Philip and that has put an end to that.”

“Cassie, when I go to London, Grand’mere is coming with us.”

She looked at me in dismay.

I went on: “I have said that whenever you want to you can come and stay.”

“I will come,” she cried. “No matter what Mama says.”

I told her about the house and the big top room which had been designed by an artist. She listened avidly and because I did impress on her that she would be welcome to visit us whenever she could she grew a little less melancholy at the thought of our departure.

I was expecting Philip at any moment, but he did not come. I could not imagine where he was. If he had been going out somewhere, surely he would have told me.

He had still not come back at dinner time, and the meal was delayed for half an hour; and still he had not returned.

We ate uneasily, for now we were beginning to be alarmed.

The evening wore on. We sat in the drawing room, our ears strained for sounds of his arrival. Grand’mere joined us. We were very worried.

We asked the servants if any of them had seen him go out. No one had. Where was he? What could have happened?

As the evening wore on so did our anxiety increase.

I was shivering with apprehension. Grand’mere put her arm about me.

I said: “We must do something.”

She nodded.

Clarkson thought he might have had an accident in the forest … broken a leg or something. He could be lying somewhere … helpless. He said he would get some of the men together and organize a search.

I felt limp. In my heart I knew something terrible had happened.

It was nearly midnight when they found him. He was in the forest not so very far from the house.

He was dead … shot through the head. The gun was one of those from the gunroom of The Silk House.

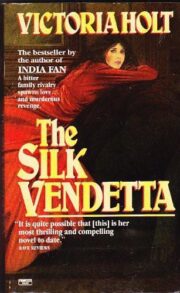

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.