Madalenna came in.

“Maria!” she cried and spoke in rapid Italian. Maria threw up her hands to the ceiling. I left them together, still puzzled.

Within an hour they were ready to go. Cassie, Julia and I with the Countess went down to wave them farewell. Madalenna again expressed her gratitude. She said: “I will write.”

Then they were gone.

When Charles and Philip returned that night and Charles heard what had happened he went white with anger.

He glared at Philip. ”There was no need for me to have gone to London,” he said. “You could have done everything without me.”

“My dear fellow, your presence was necessary. Don’t forget we are partners. We had to have your signature on the documents.”

“Where have they gone?” demanded Charles.

Julia said: “Her uncle is ill. They’ve gone back to Italy.”

“I could have driven them to London.”

“They went in their own carriage. The driver came down with it. Her brother had sent him.”

“Where did they go?”

“To London, of course … for a night … perhaps not that,” I told him. “She did say that they might leave for Italy tonight. They were in a great hurry.”

Charles turned on his heels and left us.

I said to Philip that night: ”I think he really did care for her.”

Philip was inclined to be sceptical. He said: “He is just annoyed that the chase is over before the capture.”

“Are you a little cynical about your brother?” I asked.

“Shall I say I know him well. In a few weeks he will find it difficult to remember what she looked like. He is not a faithful-to-one-woman-type like his brother.”

“I am glad you are that type, Philip,” I said fervently. “You were not in the least overwhelmed by the charms of the siren.”

”There is only one for me today … tomorrow and for ever.”

In my happiness, I could feel sorry for Charles.

Three days after their departure two letters came—one was for Charles, the other for Lady Sallonger.

Lady Sallonger could not find her spectacles so I was called upon to read hers to her. It was a conventional little note saying how Madalenna would never forget the kindness of being taken in and looked after so wonderfully. She could never express her gratitude.

The address was a hotel in London.

Charles’s must have been the same. He went up to Town the next day and called at the hotel, but of course by that time she had left.

“That little episode is over,” said Philip.

* * *

When Philip went to London, I was with him. I think Grand’mere was a little sad to see me go, but her joy in my marriage overshadowed everything else and it was a constant delight for her to see how it was between us.

The London house seemed different now. Before it had been rather alien—very grand, the Sallonger Town House. Well, now I was a Sallonger. The house belonged—at least partly—to my husband; and therefore it was in a way my home too.

The elegant Georgian architecture appeared less forbidding; the all but nude nymphs, who supported the urns on either side of the door, seemed to smile a welcome at me. Greetings, Mrs. Sallonger. I thought I should never get used to being Mrs. Sallonger.

The butler looked almost benign. Did I really detect a certain respect in the crackle of Mrs. Camden’s bombazine?

“Good evening, Madam.” How different from my last visit when I was plain Miss—not exactly a servant—but not of the quality either—a kind of misfit.

That had changed. The proud gold ring on my finger proclaimed me a Sallonger.

“Good evening, Evans. Good evening, Mrs. Camden,” said Philip. “We’ll get up to our room first I think. Please have hot water sent up. We must wash away the stains of the journey.” He took my arm. “Come along, darling. If you’re anything like me you’re famished.”

I was conscious on every side of my newly acquired status. I would tell Grand’mere about it when I saw her. We would laugh together and I would give an imitation of Mrs. Camden’s very gracious but slightly hesitant condescension.

I loved being in London with Philip. He was so enthusiastic about everything. He talked unceasingly and it was usually about the business. I did not have to feign interest. He said he would take me to the works at Spitalfields. “It’s wonderful,” he said, “to have a wife who cares about the things I care about.”

I vowed that I would learn more and more. I would please him in every way. I was so glad that Grand’mere had taught me so much.

My complete pleasure was spoilt by the presence of Charles. He was still sulking about Madalenna and seemed to think that we had deliberately refused to find out where she was going. Apparently his letter had been on the same lines as that she had written to Lady Sallonger–just a conventional thank-you letter; and he had no more idea where she had gone than we had. All he knew was that she had written from that particular hotel. Philip told me that Charles had been there several times but could get no information as to her address in Italy.

I would sometimes find his eyes watching me … almost speculatively and there was an expression in them which I could not fathom; but I did not think it was one of brotherly love.

I was glad when Julia and the Countess came to the house. Julia had had her little respite and was now once more in search of a husband.

I was becoming friendly with the Countess. She told me how much she admired Grand’mere who had made a niche for herself and kept her dignity; and now her granddaughter had married into the family. The Countess thought that was a very happy conclusion.

She and Julia went out a great deal. There was constant discussion about Julia’s clothes. Often the Countess would call me in to ask my advice.

“You have a flair,” she said.

She admitted that she had one, too.

I liked her very much; and one morning when Julia was in bed—she invariably slept late after her social engagements—the Countess and I talked together. She was very frank. She said she thought her work was rather futile. She would like to do something worthwhile. She spoke of Grand’mere. “What a dressmaker! None of the court people can compare with her. How I wish I could do something more to my taste.”

“Have you any idea what?”

“Something in the dress line. I’d like to have a shop … all the very best clothes. I’d make it famous throughout Town.”

I often remembered that morning’s talk.

But at that period my time was mostly taken up by Philip. He gave me a book to read which he said would enhance my interest in silk and tell me something of its romantic beginnings. I found it fascinating to read how nearly three thousand years before the birth of Christ the Queen of Hwang-te was the first to rear silkworms and how she prevailed upon the Emperor to have the cocoons woven into garments. So the art of silk-weaving became known in the time of Fouh-hi who lived a hundred years before the Flood. But this all took place far away and it was not until the sixth century a.d. that two Persian monks brought knowledge of the process to the Western World.

Philip would talk enthusiastically about the beginnings of the industry and how important it was that the worms should be fed on the right kind of mulberry. He greatly regretted that it was not possible to rear them effectively in this country and the importing of so much raw materials was necessary.

He took me to the works and I learned something of the processes through which the materials were put. I saw the large reels called swifts, and watched the people at work. I saw the manipulating of the hanks; and Philip was delighted to see my growing interest.

He took me to the shop. It was scarcely a shop by normal standards. It was more of an establishment, discreetly curtained and presided over by a certain Miss Dalloway who was the essence of elegance and known throughout the building as Madam. There I saw displayed some of the gowns which Grand’mere had made. They seemed like old friends and much grander here than they had appeared in the workroom on Emmeline, Lady Ingleby and the Duchess of Malfi.

I was even more fascinated by the place than I had been by the workrooms and I asked Miss Dalloway a great many questions. Since the introduction of Sallon Silk there had been a great rush of business. The place had a reputation and reputations were all important when it came to clothes. The label inside could be worth a fortune. People liked a dress because it came out of the Sallonger stable. Produce the same dress without the magic label and it would only be worth half the price.

I contested the point with her saying that if the two were the same, they must be of equal value. She smiled at me in her worldly-wise way.

“The majority of people need others to think for them,” she explained. “Tell them something is wonderful and they believe it. If you were in the business you would see at once what I mean.”

I talked to Philip about it afterwards and he agreed with Miss Dalloway.

“If one intends to be successful in life,” he said, “there is one truth to be learned. One must understand people and the way their minds work, the way they think.”

Oh yes, they were happy days; but I still felt a little uneasy about Charles. He was always polite, but I would be uncomfortable if I found his eyes on me.

He will always be there, I thought. It is his home as well as ours.

Certainly his presence spoilt my pleasure in London.

Philip was very discerning. He knew of the Aldringham episode and that Drake had fought Charles and thrown him in the lake because of what he had done to me.

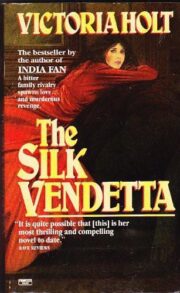

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.