I swore it had a look of our Lorenzo. We tried to discover resemblances and asked ourselves whether our Lorenzo came here to study his famous namesake.

There was so much to see—a surfeit of riches. One should have lived there for a year and assimilated it gradually; the many palaces; il Bargello which had been a prison; the Palazzo Vec-chio; the Uffizi and the Palazzo Pitti; we loved to linger in the Piazza della Signoria with its collection of statues and Loggia dei Lanzi under whose porticos were some of the most exciting sculptures I had ever seen.

The weather was gently warm but not hot. The skies were blue and gave an added beauty to those all imposing buildings.

While we were looking at the sculptures in the Piazza della Signoria, I noticed a man standing nearby. He caught my eye and smiled.

“What a wonderful collection,” he said in English with a strong Italian accent.

“Beautiful,” I answered.

”Where would you find anything like it outside Italy?” added Philip.

“I would venture to say nowhere,” replied the man. “You are on holiday here?”

“Yes,” answered Philip.

“Your first visit?”

“Not mine … but my wife’s first.”

“You speak in English,” I commented. “How did you know we were?”

He smiled. “One has a way of knowing. Tell me, what part of England do you come from? I was there myself once.”

“We are near Epping Forest,” Philip told him. “Have you ever been there?”

“Oh yes. But it is beautiful … and so near the big city, is it not?”

“I see you are well informed.”

“You are staying here long?”

“We have another week after the end of this.” He raised his hat and bowed. “You must enjoy what time is left.”

When he had gone I said: “He was very affable.”

”He liked us because we were admiring the sights of his country.”

“You think that was what it was? He seemed quite interested in us … asking where we came from and when we were leaving.”

“That,” said Philip, “is just idle conversation.” He tucked his arm in mine and we went off in search of a restaurant where we could sit and watch the activity of the streets while we ate.

We went to the opera. I was wearing my blue Sallon Silk gown and Philip his black cloak and the hat for which Lorenzo had shown such fervent admiration.

Lorenzo came into our room on some pretext just as we were about to leave. He clasped his hands and stood regarding us with admiration; and I knew he was imagining himself in Philip’s hat and cloak. He clapped his hands and murmured: “Magnifco! Magnifico!”

That was a wonderful night—the last of the wonderful nights. It seems incredible looking back that one can be so oblivious of disaster so close.

The opera was Rigoletto; the singing was superb; the audience appreciative. I was completely enchanted by the magnificent voices of the Duke and his tragic jester. I thrilled to Gilda’s Caro nome and the quartette with the flirtatious philandering Duke intent on pursuing the girl from the tavern mingling with the tragedy of betrayed Gilda and the revengeful Rigoletto. I thought: I must tell Grand’mere all about this.

During the interval I looked up at one of the boxes and in it I saw the man who had spoken to us in the Piazza. He caught my eyes and recognized me, for he bowed his head in acknowledgement.

I said to Philip: “Look, there is that man.” Philip looked vague. “Do you remember we saw him in the Piazza?”

Philip nodded vaguely.

As we came out into the street I saw him again. He was standing as though waiting for someone. Again we acknowledged each other.

“Perhaps he is waiting for his conveyance,” I said.

We ourselves decided to walk to the Reggia.

That was an enchanted evening. I wanted it to go on and on. We stood, side by side, on our balcony for a while looking down.

“When there are no people in the streets they look sinister,” I said. ”One begins to ask oneself what violent deeds were done down there in days gone by.”

“That would apply to anywhere,” said practical Philip.

“But I think there is a special quality here. …”

“You are too fanciful, my darling,” said Philip drawing me inside.

We had spent the day walking and after dinner we were rather weary. Lorenzo had hovered about us while we ate in the almost deserted dining room.

“You do not go to the opera thisa night?” he asked.

“No. We were there last night,” Philip told him.

“It was wonderful,” I added.

“Verra nisa. Rigoletto, eh?”

“Yes. The singing was superb.”

“And tonight you notta go again?”

“Oh no,” said Philip. “Tonight we are going to retire early. We have some letters to write. We are rather tired so we shall have an early night.”

“That is gooda …”

We returned to our room. We wrote our letters. Mine was a long one to Grand’mere telling her about the wonderful sights of Florence and our visit to the opera. Philip had had news from the factory and was absorbed in replying.

We sat on the balcony for a while afterwards and went early to bed.

Next morning breakfast was late in arriving and when it did come it was not brought by Lorenzo but by one of the others.

“What has happened to Lorenzo?” I asked.

His English was not good. “Lorenzo … has gone.”

“Gone? Gone where?”

He set down the tray and looked blank, raising his hands in a gesture of helplessness.

When he had gone we talked about Lorenzo. What could have happened? It could not mean that he had gone altogether.

“I should have thought he would have told us if he were having a day off,” said Philip.

“It’s odd,” I agreed. “But then Lorenzo is rather odd. I daresay we shall hear in due course.”

But when we came downstairs no one knew of his whereabouts, and it was clear that they were as surprised as we were about his disappearance.

“He’s on some romantic mission, I daresay,” said Philip.

We went out and wandered about the city. We passed the Medici Palace and with our Lorenzo in mind we talked of that other Lorenzo, scion of that notorious family which had had sovereign power over Florence in the fifteenth century.

“Lorenzo il Magnifico,” mused Philip. “He must have been a very great man to be universally known as such. Well, he was magnificent. He gave much of his great wealth to encouraging art and literature and made Florence the centre of learning. You know, he gave great treasures to the library which he founded; he surrounded himself with some of the most famous sculptors and painters the world has ever known. That is magnificent. I believe he became too powerful in the end and that is not good for anybody; and by the time he died in Florence he had lost some of his power. The sons of great men often do not match their fathers and there followed troublous times for Florence.”

I could not stop thinking of our Lorenzo.

“I hope there is no trouble when he returns,” I said. “I should imagine they will not be very pleased with him … walking out like that without saying where he was going.”

We shopped on the Ponte Vecchio and walked along by the Arno where, Philip said, Dante had first encountered Beatrice.

I was rather glad to return to the Reggia because I could not get Lorenzo out of my mind.

There a shock awaited us.

As soon as we entered the hotel we knew that something was wrong. One of the waiters with two of the chambermaids came hurrying up to us. We had difficulty in understanding what they were saying for they all spoke at once and in Italian with only a smattering of English.

We could not believe that we had heard correctly. Lorenzo was dead.

It seemed he had been attacked soon after he left the hotel on the previous night. His body had been left in one of the little alleyways at the back of the hotel and discovered only this morning by a man on his way to work.

The manager came up.

“It is good that you are back,” he said. “The polizia they wish to speak… I must let them know that you are here. They wish to speak…”

We were astounded, wondering why they wished to see us, but we were so stunned remembering the exuberant laughing Lorenzo now dead that we could think of little else.

Two members of the police arrived to talk to us. One spoke fair English. He said they had not identified Lorenzo for some time because he was wearing a cloak with a label inside and that label was the name of a London tailor. They had thought that the victim of the attack was a visitor to Florence. But he was not unknown in the city and was soon identified. They surmised that the object of the attack was robbery, but it was difficult to say whether anything had been stolen.

We were puzzled. Then I remembered Lorenzo’s admiring himself in Philip’s opera hat. I said I wanted to go to our room. I did so. The hat box was empty; nor was the cloak in the wardrobe.

I hurried down to tell them.

As a result we were taken to see the bloodstained cloak. There was no doubt whatsoever. It was Philip’s. By that time the hat had been found. As soon as I saw it I guessed what had happened.

We were very upset for this touched us deeply. We had been amused by Lorenzo and enjoyed our encounters with him. I remembered that he had particularly asked us if we should be out that night, and knowing that we should not be, he had taken Philip’s cloak and hat and so had been mistaken for a wealthy tourist and met his death.

It was so tragic and we felt deeply involved because he had been killed in Philip’s clothes. I kept thinking of him, sauntering along, feeling himself to be a very fine figure of a man, irresistible to women. His vanity had killed him; but it was such a harmless, lovable vanity.

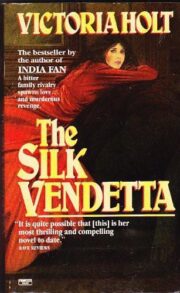

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.