Lady Sallonger was growing resigned though she was still a little resentful. “Three weeks,” she said. “It seems such a long lime. We shall have to finish The Woman in White before you go.”

“Miss Logan would read it to you,” I reminded her.

“She gets so hoarse … and she doesn’t put the feeling into it.”

“Cassie …”

“No, Cassie is even worse. She has no expression, and you don’t know whether it is the heroine or the villain talking. Oh dear, I don’t know why people want to have honeymoons. It can be so inconvenient.”

“I am flattered that you miss me so much,” I said.

“I am so helpless now … and with Sir Francis gone … there is no one to look after me.”

“We all look after you as we always did,” I protested. I was on a different status now … no longer merely the granddaughter of someone who worked for them but the prospective daughter-in-law. It gave me standing, and I intended to use it.

And so happily the weeks passed until my wedding day came.

It was a bright April day. The doctor who was a friend of the family “gave me away” and Charles was the best man.

As I stood there with Philip a shaft of sunshine came through the glass windows and shone on the plaque dedicated to that Sallonger who had bought the house and changed its name to Silk. Philip took my hand and put the ring on my finger and we vowed to cherish each other until death did us part.

We came down the aisle to the sound of Mendelssohn’s Wedding March and I caught sight of Grand’mere’s beaming face as I passed.

Then we went back to The Silk House and there was a small reception for the guests. We were congratulated and well-wished; and in due course it was time for us to prepare to leave.

Grand’mere was with me in my bedroom; she helped me out of my splendid wedding gown and into the dark blue alpaca coat and skirt which she had deemed ideal for travelling.

When I was ready she was beaming with pride and joy.

“You look beautiful,” she said, “and this is the happiest moment of my life.”

Then Philip and I set out for Florence.

They were days to treasure and remember for ever. I was happy. I now had no doubt whatsoever that Grand’mere had been right when she was eager for me to marry Philip. Now that we were in truth lovers, I had discovered a new happiness which was a revelation to me. This closeness to another person, this newly found intimacy was exciting, exhilarating and wonderful. I had never been lonely. Grand’mere had always been there, the centre of my life; but now there was Philip, and with him I had this special relationship. Philip was so good to me, anxious to make me happy. I was his first consideration. It made me feel humble in a way and very contented to be so loved. Grand’mere had known how it would be and that was why she had been so anxious for me to marry Philip.

Not only was he deeply enamoured of me, a gentle yet passionate lover, but he seemed to have an immense knowledge about so many subjects. I had always known that he was vitally interested in the production of silk—and I was learning that when Philip was interested, the smallest detail was of importance to him—but his love of music was great, and I had always been attracted by it, and when I was with him I came to a great understanding and therefore appreciation of it. He loved art. He was very knowledgeable about the painters of Florence, some of whom, like Cimabue and Masaccio, I had never heard of before. He was interested in the past and could talk so vividly of Florentine history that I almost saw it happening before my eyes.

As it was April there were not many visitors in Florence. I imagined that later on the place would be crowded for it was indeed one of the show places of Europe. There were very few people staying in the hotel which meant that we had the full attention of a staff which I was sure would be added to when the hotel was full.

The rooms were large and lofty; our bedroom had tiled walls of mauve and blue mosaic. The french windows opened onto a balcony so that we could look down on the street below. It was very large. I think it had once been a palace for there was a certain rather shabby grandeur about it. It was called simply Reggia. There was something about it which struck me as being rather eerie. I think I should have felt that more strongly if I had been alone. But as Philip and I were together I quite enjoyed the loneliness and that strange rather uncanny feeling that in this place strong emotions had occurred—some of them sinister, which added to the fascination.

They were golden days. Everything seemed exciting and amusing. Philip had a way of looking at things to make them so. I had thought he was obsessed by his business—and to a certain extent he was. We used to wander round the streets looking in the shop windows which displayed silks. He could never resist stopping and sometimes going into the shops to enquire about prices, to feel the weight of the material and caressing it fondly with his fingers. I used to laugh at him about it and tell him that the shopkeepers would be annoyed with him because he never bought anything.’ ‘Well,” he said,’ ‘that would be like taking coals to Newcastle.”

I loved the little shops on the Ponte Vecchio. We would pore over the trinkets and sometimes buy a stone or a bracelet or a little enamelled box. There was so much to interest us.

We were looked after by a lively Italian. I did not know what lie did in the hotel when it was full, but as there were so few guests he attached himself to us and became a kind of general factotum.

He brought our breakfast in the morning. He would draw back the curtains and stand surveying us with an indulgent smile. If we left clothes lying about he would hang them up, for he took a great interest in our clothes, particularly Philip’s. He spoke a little English interspersed with much Italian and obviously he liked to practise it on us. We were very amused by him and as the days passed we began to encourage him to talk.

He was tall… about Philip’s height; and he had dark brown hair and large dark soulful eyes.

He quickly discovered that we were on our honeymoon.

“How did you guess?” I asked.

He lifted his shoulders and raised his eyes to the painted ceiling.

“It is possibla to tella.” He put an “a” on the ends of most of his words and uttered them in a singsong voice which was totally un-English.

“Verra nisa,” he said. “Verra nisa.” And seemed to think the matter was a great joke.

He looked upon us as his proteges. When we ate in the restaurant he would come down and stand with the waiter watching us eat. If we did not do justice to one dish he would shake his head and ask anxiously: ”Notta nisa?” in that voice which made us want to laugh.

He was very dashing and dandy in appearance. One constantly saw him gazing at his reflection in mirrors with a look of complete satisfaction. His name was Lorenzo. Philip christened him Lorenzo the Magnificent.

As the days passed he became more and more loquacious. Philip had a certain understanding of Italian and between that and Lorenzo’s English we learned a great deal. We encouraged him to talk. Everything seemed incredibly amusing and we laughed a great deal. It was the best sort of laughter that had its roots in happiness rather than amusement. I think we were both so glad to be alive.

Lorenzo sensed this and it was as though he wanted to be part of it.

He wanted us to know what a fine fellow he was, beloved of the ladies. In fact, he conveyed to us, it grieved him that there were occasions when he had to shake them off. His hands were expressive and he made motions as though brushing away tiresome flies. He always placed himself conveniently near a mirror during these discourses so that he could throw glances at himself; he would pat his curls approvingly. But in spite of his blatant vanity there was something lovable about him and neither of us could resist talking to him.

As I said he was very interested in Philip’s clothes. Once we had come into the room and found him trying on Philip’s opera hat.

“Verra nisa,” he said, not in the least abashed to be caught.

We tried not to show surprise, but we were never really surprised at anything Lorenzo did.

“It suits you,” I said.

“In this … Lorenzo … he maka the big capture, aha?”

“I am sure you would. You wouldn’t be able to brush them off. You would have to take flight.”

Reverently he took the hat, collapsed it with almost childish pleasure and reluctantly put it into the box.

He used to tell us where to go and question us on our return. He was a source of great amusement to us. We laughed about his preening himself in Philip’s hat.

“Have you ever seen anyone so vain?” I asked.

Philip replied that he was probably no vainer than other people, but he just did not hide it.

“He sees himself as the great lover,” he went on. “Well, why not? It makes him happy. There is no doubt about that.”

There certainly was not.

Sometimes we would sit in one of the open-fronted restaurants drinking coffee or sipping an aperitif. We would talk about where we had been that day and what we proposed to do the next and we never failed to talk about the latest exploits of Lorenzo.

Magic days in a magic city. When I think of Florence I think of the heights of Fiesole; I think of houses encircled by sloping hills covered with vineyards, gardens and beautiful villas; I think of the rather austere Florentine buildings which gave a certain sinister grandeur to the streets; I remember particularly the Duomo—the Cathedral—and the church of San Lorenzo with its magnificent marbles and decorations of lapis lazuli, chalcedony and agate; I discovered a statue of Lorenzo de’ Medici— Lorenzo the Magnificent.

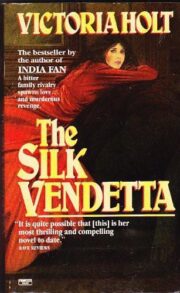

"The Silk Vendetta" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Silk Vendetta". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Silk Vendetta" друзьям в соцсетях.