They spent half an hour with Mara, telling her about the day, how Sheila had taken Sam to the beach and allowed him to remove his shoes so the waves could tease him with the frigid water, how Liam had handled a difficult case in the E.R. He never talked down to her, and he always hoped that, if he spoke about a case that had a meaty psychological component, he might tap into the part of Mara’s brain that had once come alive with the challenge of helping a deeply troubled patient. Then they focused on Sam, who often grew impatient with the chatter. The little boy needed action. They played huckle-buckle-beanstalk, “hiding” the small pot of silk daisies that ordinarily rested on Mara’s night table in various places around the room. They made sure the daisies were always in plain sight, but it still took Sam minutes to find them each time, and he would let out a yelp and holler, “huh-buh-besawk!” when he did. It made them laugh, made Mara’s smile grow wider, although Liam doubted she understood the game. After the fourth time they hid the flowers, Liam noticed Mara’s eyelids growing heavy and knew she’d had enough of her visitors for today.

“Let’s go,” he said to Sam, lifting him into his arms.

Sam let out a sound of pure desolation, pointing to the daisies as Sheila placed them back on Mara’s night table. “Huh-buh-besawk,” he said, but it came out as a grief-stricken moan.

Liam grinned and kissed his temple. “Sorry, sweetheart,” he said. “We can play some more when we get home.”

“And someday, maybe Mommy will be able to play it with you, too,” Sheila said, and Liam gritted his teeth. He hated it when she talked like that. Hated her denial of Mara’s condition, although to tell the truth, he had a bit of it himself. When Sam was old enough to understand, he would have to put a stop to Sheila’s verbal wishful thinking.

He leaned over to kiss Mara on the cheek. Her eyes were now closed, and he knew she was no longer aware of his presence.

They walked through the corridor toward the foyer, stopping briefly to speak with one of the nurses about Mara’s medical treatment, and as they were walking out of the building, Joelle was walking in. Thursday night. Joelle always visited Mara on Thursday nights. He’d forgotten and hadn’t been prepared to see her, and now, his defenses down, he felt a rush of love, gratitude and the adrenaline that accompanied desire. Followed quickly by guilt, the impulse to run from her rather than to her.

“Hello, Joelle,” Sheila said with the cool edge to her voice that Liam had noticed recently when she spoke to—or about—Joelle. He worried that, somehow, Sheila knew that he and Joelle had become very close. Too close.

Sam instantly reached toward her, and Liam transferred the little boy from his arms to hers, his hand accidentally brushing her breast as he did so. He flinched inwardly at the touch, but Joelle pretended not to notice. She nuzzled Sam’s neck.

“Hello, sweetie pie,” she said. “How’s my boy?”

She smiled at Liam but quickly riveted her gaze on Sheila, and Liam understood. She, too, felt the discomfort in looking directly at him.

“How’s Mara this evening?”

Stupid question, Liam thought. Everyone knew how she was. The same as she’d been for months. But they all played the game, anyway.

“She’s full of smiles, as usual,” Sheila said.

“I’m afraid we wore her out, though,” Liam added. “I’m sorry. I forgot it was Thursday.”

“That’s all right,” Joelle said as she handed a squirmy Sam back to his father. “I’ll just sit with her. Hold her hand.”

“That would be nice,” Sheila said, and she proceeded past her through the doorway.

“See you tomorrow,” Liam said, following his mother-in-law outside.

Once on the sidewalk, he set his son down, and Sam started his toddling exploration of the landscaping.

“What’s with you and Joelle?” Sheila asked as they walked toward the parking lot.

“What do you mean?”

“I’ve picked up a little ice between the two of you lately.”

“Your imagination,” Liam said, but he was certain he heard some satisfaction in Sheila’s voice. He recalled some of his mother-in-law’s recent comments about Joelle: “She only comes to see Mara once a week,” she’d say. “And to think they had once been best friends!” Or, “I didn’t like that shirt Joelle was wearing today. It makes her look fat.”

Liam buckled Sam into the car seat, then stood up to give his mother-in-law a quick hug. “Thanks,” he said. “My pleasure.”

“Hope I don’t need to call you again tonight.” He opened the driver’s-side door.

“I’m available if you need me,” she said, the warmth back in her voice. She waved bye-bye to her grandson through the car window, then turned to walk toward her own car.

Liam pulled into the street, turning in the direction of home, knowing he’d have to fix something to eat once he got there and feeling overwhelmed by the thought of that simple task. He hated this depressed feeling that had come over him lately. He’d made it through an entire year without Mara, the Mara he’d known and adored, and he’d been depressed but still strong and resilient. The one-year anniversary, though, had kicked him in the back of the knees. Two months ago had been Sam’s first birthday, the date that would always mark the moment Mara lost her body and mind, if not her spirit. The day that everything changed. Forever, said her doctors. She would never be the same. She would never be the woman he had fallen in love with.

He’d celebrated Sam’s birthday with Sheila and Joelle, none of them mentioning the other event marked by that date. There was something about a year that made it so final. A year of growing as a person, as a doctor, as a first-time mother. It had all been snatched away from Mara. And from him.

But despite his aversion to Sheila’s veil of denial, he would not allow himself to give up hope, and he pulled into his driveway with new determination. Once he’d fixed supper, washed the dishes and settled Sam into bed for the night, he would do what he’d been doing ever since the day of his son’s birth: he would log on to the internet and visit the website where people had written anecdotes about their friends and relatives who had suffered an aneurysm. And there he would find stories of hope. Stories of miracles. They would make him believe, if only for a moment, that the wife he still loved would one day be able to hold her son in her arms.

3

JOELLE LISTENED TO A NOVEL ON TAPE AS SHE DROVE TOWARD Berkeley and her parents’ home. She kept having to rewind it, because her mind was wandering, and finally she turned the tape off altogether. Fiction no longer seemed as gripping to her as her own life.

It was her father’s birthday, and she’d promised to make the two-hour drive to Berkeley to help him celebrate. Celebrate was probably the wrong word. It was to be a quiet dinner, just her parents and herself. Her parents weren’t much for birthdays. Gifts, for example, were not allowed. She had received no birthday gifts from her parents in all the thirty-four years of her life, although she’d received many gifts from them at other times. Her parents didn’t believe in giving because you were expected to, but rather because you were moved to. Nor did her parents believe in celebrating holidays. No Christmas. No Hanukkah. They attended some tiny Berkeley church, the denomination of which Joelle could never remember, that honored the sacred spirit in all of nature, and Joelle was never surprised to find a pot of dried leaves or a bowl of shells or fruit on the so-called altar in their so-called meditation room. No one was allowed in that room unless they were there to meditate. For two people who eschewed society’s rules and traditions, Ellen Liszt and Johnny Angel had created plenty of their own.

That was the way Joelle had been raised. She’d lived the first ten years of her life as Shanti Joy Angel in the Cabrial Commune in Big Sur. It was a time she remembered with remarkable clarity: eating a strictly vegetarian diet, worshiping nature, learning not to play too near the edge of the cliffs, the way some children learned not to play in the street. Growing up there, she’d taken the magic of Big Sur for granted. Sometimes now, though, she remembered it with longing. She missed the view of the bluffs carving their way through the blue and green water, the dark, cool forest, the ubiquitous fog that washed over them in the morning and late afternoon, which made games of hide-and-seek thrilling and scary. You never knew who or what was mere inches away from you. Her mother and a few of the other parents had taught the children in one of the cabins, the commune’s one-room schoolhouse, and by the time Joelle entered public school, she had been far ahead of her classmates.

She had been grateful, then, that she’d spent ten years in the commune. Her life there had given her skills that other children did not seem to have. She could talk with anyone, of any age group, about nearly any subject. The commune had provided her with nonjudgmental acceptance and plenty of fuel for her imagination. It had taught her to take care of other people, and she was certain that was one reason she’d become a social worker.

Somehow, though, over the last twenty-four years, she’d picked up the mores and conventions of the outside world and had made them very much her own. Maybe it was the talk she’d had with her parents when she turned thirteen, three years after they left the commune, that had influenced her. For some reason, her parents began confiding in her then, apparently deciding that thirteen was the appropriate age for that sort of conversation. They had believed in free love, they told her, the sharing of partners, as well as of food and clothing and chores, and that had been fine for both of them at first. But they began to feel that age-old emotion they had been trying to suppress for a decade: jealousy. As the feeling ate away at each of them, they decided it was time to leave, to rejoin the world. Maybe the way of the commune had not been intended for a lifetime, after all. Yet, although her parents were able to fit in easily in Berkeley, with its counterculture and free thinkers, Joelle doubted they could have adjusted to any other area of the country. In many ways, her parents, who had never married, were still the people they had been at Cabrial Commune.

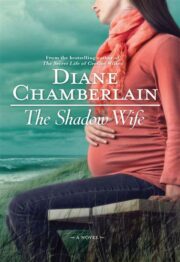

"The Shadow Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.