She and Alan shared a practice in their office on Sutter Street, where Carlynn specialized in children, while Alan saw adults. There was crossover, of course. A great deal of it, actually, because Alan often called her in to “meet” one of his patients, in the hope that such a meeting would lead him to a better course of treatment through Carlynn’s intuitive sense of the patient. It was gratifying work, something she seemed born to do. Still, she was not completely happy. All day, every day, she treated the children of other people, when what she longed for was a child of her own.

A year ago, Alan had learned he was sterile. They would never be able to have children unless they adopted, and neither of them was ready or willing to take that step. Carlynn had wondered briefly if she might be able to use her healing skills to make Alan fertile again, but she didn’t want to subject him to being a guinea pig, and he did not offer.

The news that they would remain childless had thrown Carlynn into a mild depression, which she’d attempted to mask so that Alan would feel no worse than he already did. What kept her going, what still brought her joy, was her continued fascination with the nature of her gift. She spent her days pouring her energy into her patients, but at night she was exhausted and often went to bed early, and she knew that Alan worried about her.

“Mrs. Rozak?” Carlynn spoke softly to the woman in the little boy’s room.

“Yes.” The woman stood up to greet her.

“I’m Dr. Shire,” Carlynn said. “Dr. Zieman asked me to see your son.”

“I didn’t expect a woman,” Mrs. Rozak said, obviously disappointed.

“No, I’m often a surprise.” Carlynn smiled.

“Isn’t there another Dr. Shire? A man?”

“That’s my husband,” Carlynn said. “But he treats adults. I’m the pediatrician in the family.”

“Well…” The woman looked at her son, whose eyes were open, but who had not moved or made a sound since Carlynn had walked into the room. “Dr. Zieman said that if anyone could help him, you could.” She spoke in a near whisper, as though not wanting her child to hear her. Her small gray eyes were wet, her face red from days of crying, and Carlynn moved closer to touch her hand.

“Let me see him,” she said.

The woman nodded, stepping back to allow Carlynn to move past her.

Carlynn sat on the edge of the boy’s bed. His name was Brian, she remembered, and he was awake but silent, his glassy-eyed gaze following her movements. She could almost see the fever burning inside him. Touching his forehead, her hand recoiled from the heat.

“Nothing’s brought the fever down,” his mother said from the other side of the bed.

“Hello, sweetheart,” Carlynn said softly to the boy. “Can you hear me?”

The boy gave a barely perceptible nod.

“He can hear,” the mother said.

“It hurts even to nod?” Carlynn asked him, and he nodded again.

She thought of asking the mother to leave, but decided against it, as long as she could get her to be quiet. Ordinarily, she preferred not to have family members present, since her style of work tended to alarm them because of her lack of action. They wondered why she had been called in to see their sick children, when she appeared to do absolutely nothing to help them. This particular woman was very anxious, though, and if Carlynn could keep her in the room while she worked, it would probably help both mother and son.

“Back here?” She touched the back of Brian’s neck. “Is this where it hurts?”

The boy whispered a word and she leaned closer to hear it. “Everywhere,” he said, and she studied him in sympathy.

Standing up, she smiled briefly at his mother, then lifted Brian’s chart from the end of the bed, leafing through the pages. They’d ruled out rheumatic fever and meningitis and all the other probable causes for his symptoms, as well as those that might not be so obvious. He had an infection somewhere in his body—his blood work showed that much—but the cause had not been determined. Frankly, she didn’t care what was causing his symptoms as long as the logical culprits had been ruled out. It only helped her to know the cause if it was something that could be removed or repaired. Fever caused by a ruptured appendix had one obvious solution, for example, but when a child presented this way, with intense, hard-to-control fever and pain everywhere, and the usual suspects had been ruled out, learning the cause was no longer on Carlynn’s agenda.

“No one can figure out what’s wrong with him,” Mrs. Rozak said.

Glancing through his chart again, she assured herself that every treatment her physician’s mind could imagine had already been attempted. The treatment she would now give the boy would have little to do with her mind and everything to do with her heart. Sitting down once more on the edge of Brian’s bed, she looked up at his mother.

“I’m going to ask you to be quiet for a while, Mrs. Rozak, all right?” she asked. “It’s very important, so no matter how much you want to say something to me, please save it until I tell you it’s okay. I’d like to give Brian my undivided attention.”

The woman nodded again and walked across the room to sit on the edge of the empty second bed.

Carlynn spoke to Brian in a soft voice, holding his small hand in both of hers.

“Nothing I do will hurt you,” she said. “I’m going to talk to you, but you don’t need to talk back to me,” she said. “I’m not going to ask you any questions, so you don’t have to worry about answering me. I’m just going to talk for a while and hope I don’t bore you too much.” She smiled at him.

She talked about the weather, about the Yankees winning the World Series, about the way the blond in his hair sparkled in the soft light from the lamp. She talked about Halloween coming up and about the new movie The Miracle Worker, and how strong and tough and smart Helen Keller had been as a child. She talked until she knew his gaze was locked tight to hers. Then she gently lowered the blanket and sheet to his waist.

“I’m going to touch you very gently now,” she said. “I won’t hurt you a bit.”

Through his hospital gown, she rested one hand on his hot rib cage and leaned forward so that she could slip her other hand beneath his back.

“I’m going to be quiet for a few minutes now, Brian. I’ll close my eyes, and you can close yours, too, if you like.”

Shutting her eyes, she did what had become second nature to her. She allowed everything inside her, all her thoughts and hopes and loving feelings, to pour from her into him. She could feel the energy slipping through his body, from one of her hands to the other. Sometimes, healing came easily to her, and tonight, with this particular child, was one of those times.

“There’s a light inside you, Brian,” she said softly, her hands still on his small, hot body. “It’s not a hot light, like a lightbulb. It’s cool, like the water in a cool lake, reflecting the sun off its surface. I can feel it passing into your body from my hands.” There was no need for her to speak—this was not hypnosis—but talking sometimes helped, and with this boy she thought it might. She opened her eyes to see that his were closed, a small crease in the space between his delicate, little-boy eyebrows as he listened hard to her words.

Precious child, she thought, closing her eyes again.

After another moment or so, she slowly drew her hands away from him. He was asleep, she noticed, the crease gone from between his eyebrows, and she knew he would get well. She didn’t always have that sense of certainty; in fact, it was rare that she did. Right now, though, the feeling inside her was strong.

Standing up, she pressed her finger to her lips so that Mrs. Rozak would not say anything that might wake her son.

Carlynn leaned forward to hold her wristwatch into the circle of light from the night-table lamp. She’d been in the room an hour. It had seemed like fifteen minutes to her.

Walking toward the hallway, she motioned Mrs. Rozak to follow her.

“What do you think?” the woman asked as soon as they’d reached the intrusive bright light of the corridor. The poor woman had to be thoroughly confused by what she had just witnessed, and Carlynn thought she’d probably made a mistake in allowing her to stay. She hadn’t realized how long she would be working with Brian.

“I think Brian will get well,” she said.

“But what’s wrong with him?”

“I’m not certain,” Carlynn said honestly. “But I believe he will turn the corner very quickly.”

“How can you say that?” The woman looked frantic, wiping a tear from her cheek with a trembling hand. “You didn’t even examine him.”

It was true. She hadn’t listened to his heart or his lungs or looked into his ears or his throat, and perhaps she should have allowed that ruse, but she had gotten out of the habit of pretending to do something she was not. It stole her energy from the task at hand.

She smiled at Mrs. Rozak. “I examined him in my own way,” she said. “And I feel very strongly that he will be just fine. Back playing with his friends in a week. Maybe sooner.”

She didn’t want to answer any more questions. She couldn’t. A dizziness washed over her that she knew would drop her to the floor if she didn’t escape quickly. Excusing herself from the bewildered woman, she walked down the hall to the ladies’ room.

Inside the restroom, she washed her hands in cold water, shaking them out at her sides, then splashed water on her face, trying to regain some of the energy she had just given away. God, she would love a nap! Once or twice, she’d given in to that temptation by closing herself into one of the stalls, sitting fully clothed on the toilet and resting her head against the wall while she dozed. But there was no time for that tonight.

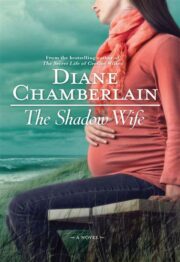

"The Shadow Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.