“If you insist.” He smiled at her, but there was a deep sadness in his eyes. Lifting her hand to his lips, he kissed it. “I care about you, Jo,” he said. “You know that. But I’m married, and as long as Mara is alive, I’m her husband. I love her.”

“Me, too,” she said.

“I’ll be there for you in whatever way I can. But…we can’t get that close again.”

“I know.” She nodded.

“I’ll help you support the baby financially, of course.”

“You’re having a hard enough time with money as it is,” she said. “I don’t expect Sheila to pay child support for my baby.”

He said nothing, and she knew she had bruised his ego. She said the word, “Sorry,” but it came out as a whisper, and she wasn’t certain if he’d heard her or not.

“Do your parents know?” he asked.

She shook her head. “No. They don’t know I’ve had surgery, either.”

“Would you like me to call them for you?”

“Would you, please? But don’t tell them about the pregnancy, okay? I’d rather do that myself. Tell them I’m fine, not to come down, not to worry, not to—”

“I’ll take care of it,” he said.

He bent over to kiss her on the forehead, and the gesture reminded her of all the times she’d seen him bend over to kiss Mara in her bed at the nursing home. Mara, though, he would have kissed on the lips.

Liam called her parents from his office. He knew John and Ellen, having spent time with them over the years, when they came down to visit Joelle. They had even come to his wedding, the only guests who took to heart his and Mara’s request for no gifts.

It was John who answered the phone, and Liam told him about the appendectomy, feeling as though he was lying because of what he was omitting from the story.

“We’re on our way,” Joelle’s father said after Liam had delivered the news.

“No, don’t come,” Liam said. “She asked me specifically to tell you not to come. Right now she’s well taken care of. Everyone here knows her and will keep an eye on her.” He recalled one of the nurses telling him that Joelle might be out of work for six weeks. “I’m not sure what her recovery will be like, though,” he said to John. “She’ll probably need some help when she gets home. That might be a better time to come down.”

“Will you keep us posted?” John asked.

“Yes, and she should have a phone in her room later,” Liam said. “I’ll call you when I get the number.”

That seemed to satisfy her father. Liam hung up the phone and sat staring at his blank computer screen.

Why hadn’t they used a condom? Two social workers, two intelligent people in their thirties. Two idiots. Yet, she had been so famously infertile, and they both knew the other was disease-free. A condom, had they stopped to think about using one, would have seemed superfluous. But if they had stopped to think, it wouldn’t have happened at all. And he knew they had both carefully, intentionally, not stopped to think.

He’d needed Joelle so badly that night. He’d needed to know he was still a man, just like that sixty-year-old man he’d seen who had the wife with Alzheimer’s.

He would visit Mara that afternoon. She would make her puppy-dog squeals when he walked into the room, and he knew exactly what she would be saying with those sounds. I remember you, she would say. You’re the one who loves me. You’re the one I can trust, no matter what. You’re my husband, in sickness and in health.

24

San Francisco, 1957

LISBETH SAT ON THE CABIN TOP OF GABRIEL’S SLOOP, MUNCHING on a pear. For the first time in her life, she did not crave candy and ice cream and cookies. Although she was dressed in knee-high rubber boots, bib overalls over a jersey, a yellow slicker, hat and gloves, she could actually feel the difference in her body beneath all that gear. Certainly, she was still larger than she wanted to be, but there was some unmistakable definition to her waistline, and although her hips and thighs were hardly slender, she could fit into the overalls without looking like an elephantine version of the pear she was eating. She had forgotten how it felt not to be tired all the time from carrying around so much extra weight.

She and Gabriel had been going together for six months, but they’d only been able to start sailing about a month ago, when the wintry San Francisco cold began to soften around the edges, and they could get out on the water without either freezing or capsizing. Their inability to sail had not interfered with their dating, however. They’d explored San Francisco together as though they were tourists, and met often for dinner at a restaurant after work. They had a few favorites, especially in the primarily Italian North Beach area where Gabriel lived, where the beats read their poetry in the coffeehouses, and where no one looked twice at a Negro man and a white woman walking or dancing together. She learned to play whist and bridge in the dark, smoke-filled clubs, and she fell in love with jazz and rhythm and blues.

She and Gabriel could talk all day and all night and never run out of things to say. He told her about growing up in the English Village section of Oakland, where a white Realtor had purchased the house his family had wanted and then transferred the title to Gabriel’s father, which had been the only way a Negro family could get into that neighborhood. His mother had been a housekeeper, his father a porter on the Southern Pacific railroad, where just about every man Gabriel knew worked. His father had died on one of the trains when Gabriel was eleven years old, killed by a fellow crew member during a game of craps.

Gabriel’s family had little money after that, and he’d worked his way through school and college. He’d met his wife, Cookie, at Berkeley, and they’d been married eight years when she discovered the lump in her breast. By the way Gabriel spoke of his late wife, Lisbeth knew he’d adored her, yet she never felt he was comparing her to Cookie. Gabriel knew how to focus on the future without letting the past get in the way, and he was teaching her, through his example, to live the same way. The fact that they both had suffered in their childhoods and their early adult years certainly drew them together, but it was their yearning to create a future that would be peaceful, bright and full of love that sealed that bond.

Dating Gabriel was not without its problems, though. Lisbeth had to find a new place to live after her landlord kicked her out the night she’d brought Gabriel up to her room. She’d only wanted to get him out of the rain while he waited for her to get ready for their date, but the landlord was livid, the tendons in his neck taut as ropes beneath his skin. He had teenage children, he yelled, as if she didn’t know, didn’t hear them playing Elvis on the phonograph at all hours of the night and day. He did not want them to witness interracial dating, and he couldn’t have a colored man in his house. So she left, finding an apartment in North Beach, four blocks from Gabriel’s, with a phone that was available for her use anytime she wanted. Her landlady was a boisterous Italian woman who didn’t care a whit what color Lisbeth’s friends were, and whose house always smelled of tomatoes and olive oil and oregano.

Now that Lisbeth no longer spent her free time huddled in her room eating, the weight dropped off her without her even trying. Diets had not been what she’d needed. All she’d really needed had been the unconditional love of a man, and that she had found in Gabriel.

She loved being out on his boat more than she enjoyed dining with him or listening to music or dancing, because out here they were alone. There was never anyone staring at them, never a look of disapproval or shock from a stranger, as there was sure to be when they ventured out of North Beach. Occasionally, someone would make a disparaging comment loud enough for them to hear, using language that belonged in a sewer, and it would only make Gabriel hold her hand tighter. Sometimes, he would apologize to her, as though the rudeness of others was his fault, and that irritated her no end. He had nothing to apologize for.

At least once every couple of weeks they got together with Carlynn and Alan. They were a compatible foursome, and they’d play bridge at Alan’s apartment, or go to a movie, or meet at Tarantino’s for cioppino. Conversation often seemed to turn to the topic of healing. Gabriel had even taken the three of them to Oakland to meet his mother, who remembered more than he did about his great-grandmother, and who filled their heads with stories they would never have believed, were it not for Carlynn.

“So, Liz,” Gabriel said now, once they were sailing smoothly downwind. “When is Alan going to pop the question to your sister?”

“This weekend,” Lisbeth said, licking a bit of pear juice from her thumb. “They’re going to Santa Barbara, and he plans to ask her sometime while they’re there.”

Alan had shown her the ring, a beautiful large diamond in a white-gold setting, and told her his plans. Lisbeth had been surprised at being taken into his confidence, but Alan had been anxious to tell her. He was a brilliant physician but a bit stuffy and private, and to see that sense of romance and excitement in him had touched her.

“Any chance she’d turn him down?”

Lisbeth laughed. “What do you think? She loves him to bits, and she’s dying to have babies.” Carlynn had found the right man, of that Lisbeth was certain. They were both bright, intense people with a passion for science and medicine and a shared curiosity about Carlynn’s ability to heal. Lisbeth herself would not have been happy with a man like Alan—not that Alan would have been happy with her, either. She needed someone like Gabriel, whose great joy in living was written all over his face.

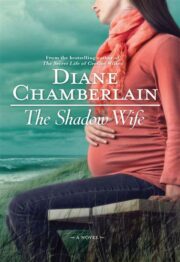

"The Shadow Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.