Mara would have been the one person to whom Joelle could have confessed what she’d done. She could have told Mara that she was in love with her best friend’s husband and that she was torn apart with guilt over having slept with him while her friend lay helpless in a nursing home. If Mara were well and could serve once again as Joelle’s confidante—and the husband in question were, of course, not Mara’s—how would she respond to that revelation? What would she say? What guidance would she offer? Mara was big on morals and ethics, but then so was Joelle. She had never done anything so flat out wrong in her life, and the experience was still tangled up in her mind and her heart. How could she regret that night, when they had comforted one another in the deepest way a man and woman could? Yet, if it cost her their friendship, and it certainly seemed to have done that, she would regret it always.

Lifting her fingers from the keyboard of her computer, she rested her hands on her belly, uncertain if the slight rise of flesh beneath her palms was the growing fetus or the product of not working out. Ten and a half weeks now. Last night, observing her body in a full-length mirror, she’d noticed that the blue-green veins in her belly and breasts were clearly visible beneath the skin, and her waistline was just starting to thicken. How long would it be before people began talking about her behind her back? She could imagine the social work department’s receptionist, Maggie, saying to Liam, “Gee, Joelle’s gettin’ a little chunky, isn’t she?”

The intercom on her desk buzzed, and she lifted the phone to her ear.

“There’s a doc here to see you,” Maggie said.

A doctor? Her first thought was that Rebecca Reed had somehow guessed she was pregnant and wanted to have a heart-to-heart talk with her.

“Who is it?” Joelle asked.

“Your name again?” Maggie asked, her voice muted a bit, and Joelle couldn’t hear the doctor’s answer. Then the receptionist was back on the line. “Dr. Alan Shire.”

What was Carlynn Shire’s odd, elderly husband doing here? She remembered him from the other day at the Kling Mansion, when he’d looked at her with a confused disapproval that she’d guessed to be a symptom of dementia. She certainly could not have him come back here to her office, where Liam might be able to overhear their conversation.

“I’ll be right out,” she said, then hung up the phone and got to her feet.

Though quite old, Alan Shire was an imposing figure in the small reception area of the social work department. He seemed taller than he had in the high-ceilinged living room of the mansion, his hair looked whiter but less disheveled, and the expression on his face was not one of confusion, but rather of deep and genuine concern. She reached her hand toward him.

“Nice to see you again, Dr. Shire,” she said. His hand felt large and strong in her own. “We’ll be in the conference room,” she said to Maggie. She led her visitor down the narrow hallway to the comparatively large room at the end, the one room that was truly soundproofed from the rest of the social work office.

“Please, have a seat.” She motioned to one of the tweed and wood chairs surrounding the long table and sat in the chair adjacent to him. “What can I do for you?” she asked.

He leaned forward in the chair, his long arms resting on the table, the fingertips touching. “I’ve come to appeal to your good judgment as a social worker,” he said.

She wished he would smile or show some lightness in his face. He had probably been handsome as a young man, although right now he looked worried and tired. In no way, though, did he look confused or slow or demented.

“What do you mean?” she asked.

“My wife…Carlynn…is retired,” he said, his blue eyes locked on her face. “She’s done no work for the center for nearly ten years, and it’s been wonderful to see her so relaxed and free.” He did smile a bit now. “She dabbles in the garden. She takes care of the house,” he said. “There’s little for her to worry about. When she was involved with patients, though, she always carried their problems around with her, trying to figure out how to help them. I don’t want to see her in that position again.”

“I understand,” she said. “But, Dr. Shire, I don’t think I twisted her arm. I simply told her about my friend, and she said she would like to meet her.” She tried to remember their conversation, examining her approach to determine if she had been coercive in any way. Unless tears could be counted as coercion, she could not see that she had.

“Yes, of course she would say she would help,” he said. “Carlynn’s a very caring person. She doesn’t like to see anyone suffer if she thinks there’s some way she can help. But you have no idea what healing takes out of her. It’s frightening, really. She’s exhausted afterward, sometimes for days. I’m concerned about her.”

For some reason, she didn’t believe him. There was nothing in his demeanor to suggest he was lying to her—in fact, he seemed nothing if not sincere—yet his words struck her as less than honest. Perhaps it was his own needs that would not be served if Carlynn were to get involved in healing again. Perhaps he had grown tired of sharing her with the rest of the world.

But then she remembered the cane. The woman’s frailty.

“Is she ill?” she asked.

He hesitated a moment before answering. “Yes, she’s quite ill, actually,” he said. “She needs her rest. And I would hate to see her go through that sort of all-consuming exhaustion that results from her healings.”

“I understand,” Joelle said. She wanted to ask him what was wrong with Carlynn, but thought better of it. Suddenly, she recalled her parents’ one concern about her contacting the healer: seeing Shanti Joy might trigger unhappy memories of Carlynn’s sister’s death.

“I was a little worried, anyway,” she said to Alan. “I was afraid that seeing me might remind her of when her sister died, since my birth and her sister’s death both took place in Big Sur, just days apart.”

He actually lit up, his eyes wide. “Yes.” He nodded. “That’s another concern I have. I didn’t know you knew about her sister, because you were…well—” he grinned, his teeth still white and straight and obviously his own “—just a couple of days old. I don’t know if you realize what a toll that accident took on Carlynn herself, both physically and emotionally.” He licked his dry lips. “I’m just so afraid that—”

Joelle held up her hands to stop him, knowing now she had no choice but to agree to his wishes. She would have to give up the fantasy of Carlynn healing Mara to save the elderly couple from painful reminders of the past, as well as from an exacerbation of Carlynn’s illness. It shouldn’t be that hard to let go of the idea; only two weeks earlier, she’d scoffed at it. Yet, she felt undeniable despair at losing the hope, no matter how slim it had seemed.

“I understand,” she said. “I won’t call her. But will you let her know that? That I’ve changed my mind? Or would she be upset that you came here?” She felt as though she was probing a bit too deeply into their relationship.

“Oh, no, she won’t be upset,” he said, standing up. “I’ll let her know we talked, and you decided against it. She’ll understand. I think she knows that she was promising something she really shouldn’t at this time in her life.”

His words made her wonder if perhaps Carlynn had sent him here to do her bidding for her.

Alan Shire shook her hand again, bowing slightly. “I’m very grateful to you for being so understanding.”

“No problem,” Joelle said. “Thank you for coming in.”

She led him back to the reception office, where Liam was collecting his mail from the wooden mailboxes on the wall. She pointed Dr. Shire in the direction of the elevators, then checked her own mailbox, although she had already emptied it earlier.

“How’s your day going?” she asked Liam.

“Good,” he said, barely glancing in her direction as he sorted through the mail in his hands. “Yours?”

“Fine,” she said.

“That’s good.” He turned and headed out the door into the hall.

Walking toward her office, she bit back tears over the emptiness of the perfunctory exchange. No smile from Liam. No “Let’s get a cup of coffee on our break.” Nothing. She had truly lost him.

The only part of him she had left was growing inside her.

12

San Francisco, 1956

LISBETH TURNED OFF THE DICTAPHONE AND PULLED THE TWO sheets of white paper, along with the carbon paper, from the typewriter. Opening the medical chart on her desk, she carefully attached the typed report to the prongs at the top of the manila folder, tossed the overused piece of carbon paper in the trash can, then filed the copy of the medical report in the four-drawer gray metal filing cabinet on the other side of the room.

At the sound of the tinkling bell hanging from the front door, she looked across the counter between her small office and the waiting area to see a young mother walk into the room, her six-or seven-year-old son at her side.

Lisbeth glanced quickly at the appointment book, then looked up as the woman approached the counter.

“Good morning, Mrs. Hesky,” she said. “And good morning, Richard. How are the two of you today?”

“We’re fine,” the woman said. “Just here for Richie’s booster shot.”

“Ah, yes.” Lisbeth could see by the stark white, unsmiling expression on Richard’s face that he was not looking forward to getting a shot. That was the only thing she disliked about working in a pediatrician’s office—it was filled with scared little children. Lloyd Peterson was known as one of the kindest pediatricians in all of San Francisco, but that made little difference when he had a syringe in his hand.

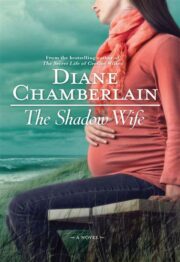

"The Shadow Wife" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow Wife". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow Wife" друзьям в соцсетях.