Once I had thought I was pregnant and it had turned out not to be so.

I was very upset about that and determined that I wouldn’t say anything to anyone next time until I was sure. Lucie was always asking pointed questions.

“When you have a child of your own …” she would say. Once she said:

“Perhaps you want a child too passionately. I’ve heard it said that sometimes when people do they can’t conceive. It’s a sort of perversity of nature.”

When I told her about Stirling’s ideas for taking up the old Christmas ceremonies as we used to in the past she thought it a good idea.

“Whiteladies is the great house,” she said.

“Wakefield Park is an upstart. I think your husband has the right idea.”

I was glad that she was beginning to like Stirling and change her suspicions about the reason why he had married me.

“When you have your family you will probably want me to leave,” she said one day.

“What nonsense!” I cried.

“This is your home. Besides, what should we do without you?”

“It won’t always be like that. I am just the stepmother-not really needed.”

“When have I ever not needed you?” I demanded.

“I shall know when the time comes for me to go,” she said.

“I wish you wouldn’t say such a thing.”

All right. We’ll forget. But I’d never stay if I weren’t wanted. “

That was good enough, I told her. She always would be.

How Stirling enjoyed planning for Christmas! A great deal of the essential work had been done on the house and he took a personal pride in it; but there was much still to be done. He had already increased the staff. Now we had six gardeners and the grounds were beginning to look beautiful. There were always workmen in the house and some rooms were out of bounds because the floor was up or the panelling being repaired.

Two weeks before Christmas I was almost sure that I was pregnant. I longed to tell someone but decided not to. I didn’t want to raise Stirling’s hopes. Oddly enough. Lizzie guessed. She was dusting Druscilla’s room, which was one of her duties, and I had gone in to see the child, who was sitting on the floor playing with her bricks, so I knelt down and we built a house together. I couldn’t take my eyes from that small face with the delicate baby nose and the tiny tendrils of hair at the brow. I was thinking of my own baby when Lizzie said in that forthright way of hers: “So it’s like that, is it?”

“Like what?” I demanded.

Lizzie cradled an imaginary baby in her arms. I flushed and Druscilla cried: “What have you got there. Lizzie?”

Lizzie said: “You’d be surprised, miss, wouldn’t you, if I told you another baby. That would put Miss Cilia’s little nose out of joint, wouldn’t it?”

Druscilla touched her little nose and said: “What’s that?”

I kissed her and said: “Lizzie’s playing.”

“You couldn’t fool me,” said Lizzie. There’s always a way of telling.”

Druscilla impatiently called my attention to the bricks and I thought:

Is it true? Is there a way of telling?

Christmas had come and gone. The Christmas bazaar had been held in the newly restored hall of Whiteladies; Stirling had provided lavish entertainment free of charge, something which had never been done before. It was a great success and everyone enjoyed our new affluence.

We entertained the carol singers at Whiteladies and soup and wine and rich plum cake were served to them. I heard one of the elder members say that it was like old times and even then they hadn’t been treated to such good wine.

We had only a small dinner-party on Christmas Day because of our recent bereavement—just the family, with Nora and Franklyn; and on Boxing Day we all went to Wakefield Park.

The new year came and then I experienced the first of those alarming incidents.

That morning at breakfast Stirling was talking—as was often the case—about the work which was being done in the house.

They’ve started on the bartizan, he said.

“There’s more to be done up there than we thought at first.”

“Won’t it be wonderful when it’s all finished,” I cried.

“Then we can enjoy living in a house that is not constantly overrun by workmen.”

“Everything that has been done has been very necessary,” Stirling reminded me.

“If my ancestors can look down on what’s happening at Whiteladies, they’ll call you blessed.”

He was silent for a while and then he said: “A big house should be the home of a lot of people.” He turned to Lucie and said: “Don’t you agree?”

“I do,” she answered.

“And you were talking of leaving us,” I accused.

“We shan’t allow it.

Shall we, Stirling? “

“Minta could never manage without you,” said Stirling, and Lucie looked pleased, which made me happy.

“Then there’s Nora,” I went on.

“How I wish she would come here. It’s absurd … one person in the big Mercer’s House.”

“She’s considering leaving us,” said Stirling.

“We must certainly not allow that to happen.”

“How can we prevent it if she wants to go?” he asked quite coldly.

“She’s been saying she’s going for a long time, but still she stays. I think she has a reason for staying.”

“What reason?” He looked at me as though he disliked me, but I believed it was the thought of Nora’s going that he disliked. I shrugged my shoulders and he went on: “Go and have a look at what they’ve done to the bartizan some time. We mustn’t let the antiquity be destroyed. They’ll have to go very carefully with the restoration.”

He liked me to take an interest in the work that was being done so I said I would go that afternoon before dark (it was dark just after four at this time of the year). I shouldn’t have a chance in the morning as I’d promised to go and have morning coffee with Maud who was having a twelfth-night bazaar and was worried about refreshments.

That would take the whole of the morning, and Maud had asked me to stay for luncheon. Stirling didn’t seem to be listening. I looked at him wistfully; he was by no means a demonstrative husband. Sometimes I thought he made love in a perfunctory manner-as though it were a duty which had to be performed.

Of course I had always known that he was unusual. He had always stressed the fact that he had no fancy manners, for be had not been brought up in an English mansion like some people. He was referring to Franklyn. Sometimes I think: he positively disliked Franklyn and I wondered whether it was because he knew that Franklyn admired Nora and he didn’t think any man could replace his father.

He needn’t have worried, I was sure. If Franklyn was in love with Nora, Nora was as coldly aloof from him as I sometimes thought Stirling was from me. But I loved Stirling deeply and no matter how he felt about me I should go on loving him. There were occasions in the night when I would wake up depressed and say to myself: He married you for Whiteladies. And indeed his obsession with the house could have meant that that was true. But I didn’t believe it in my heart. It was just that he was not a man to show his feelings.

I came back from the vicarage at half past three. It was a cloudy day so that dusk seemed to be almost upon us. I remembered the bartizan, and as Stirling would very likely ask me that evening if I had been up to look at it, I decided I had better do so right away, for any lack of interest in the repairs on my part seemed to exasperate him.

The tower from which the bartizan projected was in the oldest part of the house. This was the original convent. It wasn’t used as living quarters but Stirling had all sorts of ideas for it. There was a spiral staircase which led up to the tower and a rope banister. In the old days we had rarely come here and when I had made my tour of inspection with Stirling it had been almost as unfamiliar to me as to him. Now there were splashes of whitewash on the stairs and signs that workmen had been there.

It was a long climb and half-way up I paused for breath. There was silence about me. What a gloomy part of the house this was! The staircase was broken by a landing and this led to a wide passage on either side of which were cells like alcoves.

As I stood on this landing I remembered an old legend I had heard as a child. A nun had thrown herself from the bartizan, so the story went.

She had sinned by breaking her vows and had taken her life as a way out of the world. Like all old houses, Whiteladies must have its ghost and what more apt than one of the white ladies? Now and then a white figure was supposed to be seen on the tower or in the bartizan.

After dark none of the servants would go to the tower or even pass it on their way to the road. We had never thought much about the story, but being alone in the tower brought it back to my mind. It was the sort of afternoon to inspire such thoughts—sombre, cloudy, with a hint of mist in the air. Perhaps I heard the light sound of a step on the stairs below me. Perhaps I sensed as one does a presence nearby. I wasn’t sure, but as I stood there, I felt suddenly cold as though some unknown terror was creeping up on me.

I turned away from the landing and started up the stairs. I would have a quick look and come down again. I must not let Stirling think I was not interested. I was breathless, for the stairs were very steep and I had started to hurry. Why hurry? There was ho need to . except that I wanted to be on my way down; I wanted to get away from this haunted tower.

I paused. Then I heard it. A footstep—slow and stealthy on the stair.

I listened. Silence. Imagination, I told myself. Or perhaps it was a workman. Or Stirling come to show me how they were getting on.

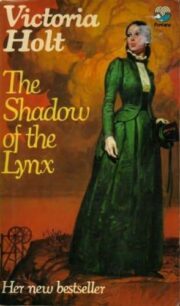

"The Shadow of the Lynx" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx" друзьям в соцсетях.