It seemed a long time before the doctor and Lucie came to us. It was in fact fifteen minutes.

Dr. Hunter was shaken; a good deal of his jaunty assurance had deserted him. No wonder! Since yesterday he had said my mother’s ailments were more or less imaginary, and now she was dead.

“So it’s true?” my father said blankly.

“She died of heart failure during the night,” said Dr. Hunter.

“So she had a bad heart after all. Doctor?”

“No.” He spoke defiantly.

“It could happen to any of us at any time.

There was nothing organically wrong with her heart.

Of course the invalid life she led was not conducive to good health.

This was a case of the heart’s suddenly failing to function. “

“Poor Mamma!” I said.

I was sorry for Dr. Hunter. He seemed so distressed; he kept his eyes on my father’s face as though he expected sympathy. Sympathy for what?

Making a wrong diagnosis? Suspecting his patient was a malingerer and treating her as such when she was seriously ill?

Lucie’s eyes were fixed on him but he avoided looking at her. Once or twice he turned his gaze on me and then hastily back to my father.

“This is a great shock,” I said.

“Yesterday she was her normal self . “

“It happens like this now and then,” said the doctor.

“Minta and her father are very upset, naturally,” said Lucie.

“If they’ll allow me I’ll make the necessary arrangements.”

My father looked at her with gratitude and the doctor said:

“That would be very satisfactory, I think.”

Lucie signed to him and they went out together, leaving me with my father in the library. He raised his eyes to my face and I could not help being aware that it was shock not grief I saw there. Nor could I fail to notice his relief.

Later we went to see Mamma; she was lying in bed, her eyes closed; the frills of her white nightdress were up to her chin. She looked more peaceful in death than she ever had in life.

Something strange had happened to the house. It was no longer the same. Mamma lay in the churchyard where our family had been buried for the last five hundred years. The family vault had been ceremoniously opened; and we had gone through the mournful burial service. The shutters had been opened, the blinds drawn up. Lizzie had been ill for a week or so after the funeral and had emerged among us, gaunt and subdued. ^ Lucie had changed too; there was a certain aloofness about her.

“My father was different; it was as though a burden had been removed from his shoulders, and although he had tried to, he could not altogether bide his relief.

But perhaps the most changed of us all was Dr. Hunter. Before my mother’s death he had been a sociable young man; ambitious in the extreme, he had been the friend of local families as well as their doctor. tie nau endeavored to make people forget his youth by his excessive confidence; he had clearly been eager to climb to the top of his profession. The change in him was subtle, but nevertheless marked-certainly to me.

I thought I understood. My mother had been ill. The pains she had complained of had been real; he had seen her, though, as a fractious, discontented woman—which she was—and had allowed his assessment of her character to cloud his judgment. It seemed clear to me that he had made a faulty diagnosis and that this had so upset his confidence in himself that it was having a marked effect on him. It would throw doubt on his advanced theories on which be was basing his career. I was sorry for him.

He called rarely at the house. None of us needed him professionally until I called him in to see Lizzie because I became worried about her. This was a week or so after the funeral and then I had a conversation with him.

“You’re not looking well yourself. Doctor,” I said.

“Are you saying ” Physician, heal thyself”?”

“I believe you are worrying about my mother’s death.”

I was immediately sorry that I had introduced the subject so abruptly, for a nervous twitch started in his cheek, and his head jerked sharply like a puppet’s.

“No, no,” he said quickly.

“It is not such an unusual case as you appear to think. It Can happen to completely healthy people. A clot of blood to the brain or heart and death can be the result. There is in some cases no warning. And your mother was scarcely a healthy woman, although there was nothing organically wrong, I have read of many such cases. I have encountered several when I was in hospital. No, no. It was not so very unusual.”

He was talking too fast and too persuasively. If what he said was true, why should he blame himself? It was unfortunate that the very day before she died he had told me that she had imagined her illness and we must ignore it.

“All the same,” I said, ‘you seem to reproach yourself. “

“Not in the least. It is something one cannot foresee.”

“I’m so glad I’m mistaken. We know that you took the utmost care of my mother.”

He seemed a little reconciled, but I was sure he was avoiding us for he never called socially at Whiteladies.

My father shut himself in his study for long periods. Lucie told me that he was more upset than he appeared to be, and the fact that for the first time he had spoken to his wife unsympathetically, filled him with remorse.

“I am trying to get him working really hard on the book,” said Lucie.

“I think it best for him.”

Lucie was wonderful during that time. She asked if Lizzie might be her personal maid.

“Not,” she said deprecatingly, ‘that I need one, nor in my position should have one. I think, though, that for a time it would do Lizzie good. She has had a terrible shock. “

I said she must do as she liked for I was sure she knew best.

“Dear Minta,” she said, ‘you are the mistress of Whiteladies bow. “

It was a thought which hadn’t occurred to me before.

Franklyn was with us constantly from the day of my mother’s death. He helped my father in all the ways which Lucie couldn’t. I often wondered what we should have done at that time without Lucie or Franklyn.

He rode over to Whiteladies every day and I could be sure af seeing him some time. We talked about my mother and how unhappy she had been and I said how sad it was that she had gone through life never enjoying it, apart from one little episode when her magnificent drawing-master had come to the house and she had fallen in love with him. I rather enjoyed talking about such things with Franklyn because his prosaic views and his terse way of expressing them amused me.

“I suppose,” I said, ‘that it’s better to have had one exciting experience in your life than go along at a smooth and comfortable level all the time . even though you do spend the rest of your life repining. “

“That seems to me & very unreasonable deduction,” said Franklyn.

“You would say that! I am sure your life will be comfortable and easy for ever and ever, unruffled by any incident, disturbing or ecstatic.”

“Another unreasonable deduction.”

“But you would never make any mistake; therefore the element of excitement is removed.”

“Why do you think it is only interesting to make mistakes?”

“If you know how everything is going to work out …”

“But nobody knows how everything is going to work out. You are being quite illogical, Minta.”

And I laughed tor the first time since my mother had died. I tried to explain to him the change in the household.

“It’s as though the ghost of Mamma cannot rest.”

“That’s pure imagination on your part.”

“Indeed it’s not. Everybody has changed. Haven’t you noticed it? But of course you haven’t. You never notice things like that.”

“I appear to be completely unobservant to you?”

“Only psychologically. For all practical purposes your powers of observation would be very keen.”

“How kind of you to say so.”

“Sarcasm does not become you, Franklyn. Nor is it natural to you. You are much too kind. But there is a change in the household. My father is relieved …”

“Minta!”

“Now you are shocked. But the truth should not shock anyone.”

“I think you should be more restrained in your conversation.”

“I am only talking to you, Franklyn. There is no one else in the world to whom I would say this. And how can we blame him? I know one is not supposed to speak ill of the dead and there for you never would. But Mamma was beastly to him, so it is only ‘natural that he should feel relieved. Lizzie goes round looking lost and yet she and Mamma were always quarrelling and Lizzie was always on the point of being dismissed or leaving voluntarily.”

That is not unusual in attachments such as theirs, and it is quite natural that she should be “lost” , as you say. She has been deprived of a mistress. “

“But poor Dr. Hunter is worse than any of them. I am sure he blames himself. He seems to avoid calling at the house.”

“It is natural that he should since the invalid is no longer there.”

“And Lucie has changed.”

“I’m sorry to hear that. She appears to be the most sensible member of the household.”

“She seems shut in, aloof, not so easy to talk to. I suppose she’s worried about Dr. Hunter. I wonder she didn’t announce their engagement when it happened.”

Why? “

“Well, as Dr. Hunter is depressed and thinks he made the wrong diagnosis… ,”

“Who said he did?”

“Well, I think he did.”

“You should not say such a thing, even to me. It’s slander when discussing a professional man.”

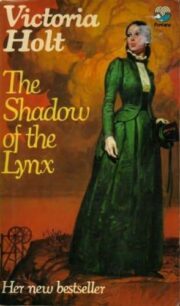

"The Shadow of the Lynx" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx" друзьям в соцсетях.