Some people might have called Franklyn dull. He was far from that.

The contrast between him and Stirling was marked. Stirling might have appeared clumsy if he had been a different kind of man; but Stirling was completely unaware of any disadvantage. He clearly was not impressed by the immaculate cut of Franklyn’s suit—if he noticed it at all.

It was difficult to make introductions, so I explained to Franklyn that the scarf had blown over the wall and that they had come to retrieve it.

Then Nora rose and said they must be going and thanked us for our kindness. Stirling was a little put out, and I was pleased because he obviously would have liked to stay; but there was nothing I could do to detain them and Lucie went with them to the gates.

That was all. A trivial incident in a way and yet I could not get them out of my mind; and because I wanted to remember it exactly as it happened, I started this journal.

We sat on the lawn until half past five then my father came down. His hair was ruffled, his face slightly flushed. I thought:

He’s had a good sleep.

“How did the work go. Sir Hilary?” asked Lucie.

He smiled at her. When he smiled his face lit up and it was as though a light had been turned on behind his eyes. He loved talking about his work.

“It was hard going today,” he said.

“But I tell myself I’m at a difficult stage.”

Mamma looked impatient and Franklyn said quickly:

“There are, I believe, always these stages. If the work went too smoothly there might be a danger of its being facile.”

Trust Franklyn to say the right thing! He sat back in the gardfil chair looking immaculate, bland and tolerant of us all. I knew that Mamma and my father had decided that Franklyn would make a very good son-in-law. We would join up Wakefield Park and Whiteladies. It would be very convenient, for the two houses were moderately close and the grounds met. Franklyn’s people were not exactly rich but, as it was said, comfortable; and in any case we were not rich either.

I believe that something had happened to our finances during the last two years, for whenever money was mentioned Papa would assume a studied vagueness which meant that this was a subject he did not wish to hear of because it bothered him.

However, it would be very convenient if Franklyn and I married. I had even come to regard this as an inevitability. I wondered whether Franklyn did too. He always treated me with a delightful courtesy; but then he extended this to everyone. I had seen the village post mistress flush with pleasure when he exchanged a few words with her. He was tall-all the Wakefields had been tall—and he managed his father’s estate with tact and efficiency, being a very good landlord to all the tenants. But behind Franklyn’s easygoing charm there was an aloofness.

His eyes were slaty grey rather than blue; there was a lack of warmth in them and one felt that if he was never angry, he was never really delighted either. He was equable; and therefore, though a comforting person to be with, hardly an exciting one. Everything about him was conventional: his immaculate dress; his courteous manners; his well-ordered life.

These facts had not occurred to me before. It was because of those two people who had invaded my afternoon that I had begun this assessment.

Well, they had gone. I never expected to see them again.

“Exactly,” Papa was saying.

“I always tell myself that I must accept this hard task for the sake of posterity?

“I am sure,” added Franklyn, ‘that you will complete it to the satisfaction of the present generation and those to come. “

My father was pleased, particularly when Lucie added earnestly: “I am sure you will, too. Sir Hilary.”

Then Lucie and Franklyn began to talk with Papa, and Mamma yawned and said her headache was coming on again, so Lucie took her to her room where she would lie down before dinner.

“Franklyn, you’ll dine with us?” said my father; and Franklyn graciously accepted.

Mamma did not appear for dinner. She sent for Lizzie, her maid, to rub eau-de-Cologne on her forehead. Dr. Hunter had been invited to dine with us but he would first spend half an hour or so with Mamma discussing her symptoms before joining us.

Dr. Hunter had come to us only two years ago and seemed young to have the responsibility of our lives and deaths, but perhaps that was because we compared him with old Dr. Hedgling whose practice he had taken over. Dr. Hunter was in his early thirties; he was a bachelor and had a housekeeper who was supposed to look after his material comforts. He was, I fancied, over anxious for our good opinion, while being aware that we considered him a trifle inexperienced. He was an amusing young man and Mamma liked him, which was an important point.

Dinner was quite lively. The young doctor had an amusing way of describing a situation and Franklyn could cap his stories often in a coolly witty manner. I was rather glad that Mamma had decided to have dinner sent up on a tray, for with her constant repetitions of her symptoms she could be a little tiresome and she most certainly would indulge in the recital of them if the doctor were present.

H I think my father was pleased, too. He was always different when she was absent; it was almost as though he revelled in his freedom.

The doctor was talking of one or two of his patients, how old Betty Ellery who was bedridden refused to see what she called ‘a bit of a boy’. “While confessing to my youth,” said the doctor, “I had to insist that my person was intact, and that I was whole and certainly not a bit of myself.”

“Poor Betty!” I said.

“She’s been in bed since I was a little girl. I remember going to her with blankets every Christmas, plus a chicken and plum pudding. When the carriage pulled up at her door and we alighted, she would cry out: ” Come in, madam, and you’re almost as welcome as the gifts you’ve brought. ” I used to sit solemnly in the chair beside her bed and listen to the stories she told of when Grandpapa Dorian was alive and Mamma used to go visiting with her Mamma.”

“The old customs remain,” said Pranklyn.

“And a good thing, too, don’t you agree, Franklyn?” asked my father.

Franklyn said that in some cases it was good to cling to the old customs; in others better to discard them. And so the conversation continued.

After dinner Lucie and the doctor sat talking earnestly while I chatted with Franklyn. I asked him what he thought of the people who had come that afternoon.

“The young lady of the scarf, you mean.”

“Both of them. They seemed unusual.”

“Did they?” Franklyn clearly did not think so and I could see that he had almost forgotten them. I felt faintly annoyed with him and turned to Lucie and the doctor. The doctor was talking about his housekeeper, Mrs. Devlin, whom he suspected of drinking more than sobriety demanded.

T hope,” said Lucie, ‘that you lock up your spirits.”

“My dear Miss Maryan, if I did I should lose the lady.”

“Would she be such a loss?”

“You clearly have no idea of the trials of a bachelor’s existence when he is at the mercy of a couple of maids. Why, I should starve and my house would resemble a pigsty without the supervision of my Mrs. Devlin. I have to forgive her her love of strong drink for the sake of the comfort she brings into my life.”

I smiled at Franklyn. I wondered whether he was thinking the same as I was. Dear Lucie! She must be nearly thirty and if she were ever going to marry she should do it soon and what a good doctor’s wife she would make! I could picture her dealing with the patients, helping him along. It was an ideal situation, although we should lose her, and what should we do without her? But we must not, of course, be selfish.

This was Lucie’s chance; and if she married the doctor, she would be living close to me for the rest of her life.

I turned to Franklyn. I was about to whisper that I thought it would be wonderful if Lucie and Dr. Hunter made a match; but one did not say things like that to Franklyn. He would think it bad taste to whisper of such a matter—or even talk of it openly—when it concerned only the two people involved. Oh dear, how tiresome he could be! And what a lot of fun he was missing in life!

I contrived it so that we talked in one group and Dr. Hunter told us some amusing stories of his life in hospital before he came to the district; and he was very entertaining. But he and Wakefield left soon after ten and we retired for the night.

When I went in to say goodnight to my mother she was wide awake.

There was a change in her.

She said: “Sit down, Minta, and talk to me for a while. I shall never sleep tonight.”

“Why is that?” I asked.

“You know, Minta,” she said reproachfully, ‘that I never sleep well.”

I thought then that we were going to have an account of her sufferings, but this was not so. She went on quickly:

“I feel I must talk to you. There is so much I have never told you. I hope, my child, that your life will be happier than mine.”

When I thought of her life with an indulgent husband, a beautiful home, servants to attend to every whim, and freedom to do everything she wanted—or almost—I could not agree that she was in need of commiseration. But, as always with Mamma, I made a pretence of listening. I’m afraid that my attention often wandered and I would murmur a sympathetic ‘yes’ or ‘no’ or ‘how terrible without really knowing what it was all about.

Then my attention was caught and held because she said:

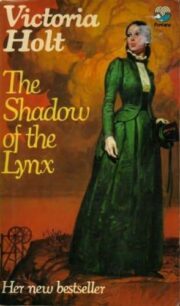

"The Shadow of the Lynx" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx" друзьям в соцсетях.