“It’s the time to sell,” he had explained.

“We’ve had most of the gilt off the gingerbread though there’s still a considerable amount in those quartz reefs. It’ll be worked for some years yet.”

He was getting rid of most of his interests in Australia because he was determined never to come back. Adelaide would stay behind for a few months and then would sell up the house and join us. It was all settled.

The sun was warm on that morning but the wind was piercingly fresh and of almost gale force. Lynx rode on ahead of our little party with the men from the mine. Stirling and I were some short distance behind. It was the first time I had been alone with Stirling since my marriage—if one could call this being-alone.

“Are you happy about going to England, Stirling?” I asked.

He said he was, and I felt angry with him. He had no will but his father’s.

“You are happy about leaving all this?” I persisted.

“And you?”

“At least I have been here a comparatively short time. It is home to you.”

“It’ll be all right in England. We had come to that spot where Jacob Jagger had lost his life. There seemed to be something eerie about it now. The ghost gums rose high and imperiously indifferent; some of the trees were blackened. So the fire had scorched this spot too. Perhaps, I thought, that is how places become haunted. A man died there … suddenly his life was brought to an end in a moment of passion. Could his spirit remain for ever, seeking revenge?

Stirling was glancing at me. Was he, too, thinking of Jagger?

“So the fire got as far as this,” I said; and my words were carried on the wind as it whistled past me.

Then it happened. The great branch fell from the top of the tallest eucalypt. There was a sudden cry as it swooped like an arrow from the sky.

Then I saw Lynx; he had fallen from his horse and was lying on the ground.

I heard someone cry: “My God, it’s a widow-maker.”

They carried him home on an improvised stretcher. How tall he looked—taller in death even than in life! He had died as one of the gods of old might have died—from a falling branch which had descended with such force that it had driven itself through his heart, impaling and pinning him to the ground. And it had happened there, not far from the spot where he had deliberately shot Jacob Jagger.

The widow-maker had caught him as it had caught lesser men before him.

I could not believe it. I went to the library. I touched the chessmen; I took his ring with the lynx engraved on it and I stared at it until it seemed as though it were his eyes which looked at me in place of those glittering stones.

Lynx . dead! But he was immortal. I was stunned. I felt as though I myself were dead.

Stirling came to see me and it was then that I was able to shed my pent-up tears. He held me in his arms and we were as close as we had been in the cave when the fire had raged above us.

“We must go to England,” he said.

“It was what he would wish.”

I shuddered and replied: “He would not wish us to go, Stirling. What good could that do? He wanted to go, but that is impossible now. It’s over.”

But Stirling shook his head and said: “He wished us to go. We shall leave as we should have done had he been here.”

I thought then that Lynx was living on to govern our lives.

Subconsciously I had always believed that death could not touch him.

Perhaps that was so.

MINTA

One

Tonight as I sat in my room looking down on the lawn I decided that I would write down what had happened. To do so would be to keep the memory of the days with me for ever. One forgets so quickly; impressions become hazy; one’s mind distorts, colouring events to make them as one would like them to have been, high-lighting what one wants to preserve, pushing away what one would rather not remember. So I would keep a sort of journal and write down everything truthfully and unvarnished just as i^i took place.

What prompted me to do this was that afternoon’s adventure, the day Stirling came. It was ridiculous really. He had come briefly into my life and there was no reason why he should appear again. It was absurd to feel this urge to write down what had happened. It was an ordinary enough incident. I knew his name was Stirling and the girl’s was Nora because they had addressed each other so—perhaps only once, but my mind had been receptive. I was more than usually alert, so I remembered every detail.

Her scarf had blown over the wall and they came to retrieve it. I had a notion that the incident was contrived. A foolish thought really.

Why should it have been?

I was on the lawn with Lucie and it was one of Mamma’s more fretful days. Poor Mamma, she would never be happy, I knew. She was looking back into a past which could not have been so wonderful as she made it out to be. It seemed that she had missed great happiness. One day she would tell me about it. She had promised to do so.

Lucie and I sat on the lawn. Lucie was working at her tapestry; she was making covers for one of the chairs in the dining-room. My father had dropped his cigar ash on the seat of one of these and burned a hole in the tapestry, which had been worked in 1701. How like Lucie to decide that she would copy the Jacobean design and provide a cover which would be indistinguishable from the rest. In her quiet way Lucie was clever and I was so glad that she was with us. Life would have been very dull without her. She could do most things; she could help my father with his work; she would read the latest novel or from the magazines and newspapers to Mamma; and she was a companion for me. I was marvelling at the similarity of her work to the existing chair seats.

“It’s almost exact,” I cried.

“Almost!” she replied in dismay.

“That won’t do. It has to be exact in every detail.”

“I’m sure we shall all be satisfied with something slightly less,” I comforted.

“Who is going to peer into it for discrepancies?”

“Some people might … in the future.” Lucie’s eyes grew dreamy.

“I want people a hundred years hence to look at that chair and say, “Which was the one which was done towards the end of the nineteenth century?”

But why? “

Lucie was a little impatient.

“You don’t deserve to belong to this house, Minta,” she scolded.

“Think what it means. You can trace your family back to the Tudors’ day and beyond. You have this wonderful heritage … Whiteladies! And you don’t seem to appreciate it.”

“Of course I love Whiteladies, Lucie, and I’d hate to live anywhere else, but it’s only a house after all.”

“Only a house!” She raised her eyes to the top of the chestnut tree.

“Whiteladies! Five hundred years ago nuns lived their sheltered lives here. Sometimes I imagine I hear the bells calling them to comp line and at night I fancy I hear their voices as they say their prayers in their cells and the swish of their white robes as they mount the stone staircases.”

I laughed at her.

“Why, Lucie, you care more for the place than any of us.”

“You’ve just taken it for granted,” she cried vehenemently and her mouth was grim. I knew she was thinking of that little house in a grimy town in the Black Country. She had told me about it, and when I thought of that I could understand her love for Whiteladies; and I was so glad that she was with us. In fact she had made me appreciate the home which had been in my family for hundreds of years.

It was I who had brought Lucie into the house. She had taught English literature and history at the boarding-school to which I had been sent, and she had taken rather special care of me during my first months there. She had helped to alleviate the inevitable homesickness; she taught me to adjust myself and be self-reliant; all this she had done in her unobtrusive manner. During my second term we had been told to write an essay on an old house we had visited and naturally I chose Whiteladies. She was interested and asked me where I had seen this house.

“I live in it,” I answered; and after that she often questioned me about it. When the summer holidays came and the rest of us were so excited about going home, I noticed how sad she was and I asked her where she was spending the vacation.

She had no family, she told me. She expected she would try to get a post with some old lady. Perhaps she would travel with her. When I said impulsively, “You should come to Whiteladies!” her delight was touching.

So she came and that was the beginning. In those days the tiresome subject of money was never mentioned. The house was large; there were many unoccupied rooms and we had plenty of servants. Often we had a house full, so Lucie Maryan was just one more. But there was a difference. She made herself so useful. Mamma liked her voice and she did not tire easily; she could listen to Mamma’s accounts of her ailments with real sympathy, for she knew a great deal about illnesses and could entertain Mamma with accounts of people who had suffered in various ways. Even my father became interested in her. He was writing a biography of a famous ancestor who had distinguished himself under Marlborough at Oudenarde, Blenheim and Malplaquet. In his study were letters and papers which had been found in a trunk in one of the turrets. He used to say, “It’s a lifetime’s work. I often wonder if I shall live long enough to complete it.” I suspected that he dozed most of the afternoon and evening when he was supposed to be working.

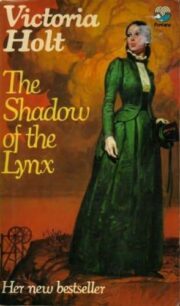

"The Shadow of the Lynx" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx" друзьям в соцсетях.