“Maybella wants me to warn you. He’s cruel and selfish. He’s lustful and he’ll not be faithful to you. He never has been to any woman, so do you think he will be to you?”

“There’s always a time to begin.”

“You’re making fun of me.”

“I’m not, Jessica. But I don’t think you understand. All that has happened is in the past. He and I are going to start a new life together. I will do everything in my power to make it a success and so will he.”

“He’ll use you as he uses everyone. What of Stirling, eh?”

“What of Stirling?” I asked.

“Well, there was a time when we thought it would be you two … it would have been natural and it was what he wanted.”

“What who wanted?”

“Stirling, of course. We all said it. A match between you two young ones … that’s what we all wanted … that’s what we all expected. And what happens? You take his fancy, so he says: ” No, Stirling, you stand aside for me and if you don’t well, I’ll shoot you as I shot that man Jagger. “

“How dare you say such a thing of him!”

“It’s what Maybella thinks. He’s told Stirling: ” Hands off. I want the girl. ” So Stirling says: ” Yes, Papa,” as he has been brought up to do.

It’s always been the same. He must have his way and the devil take the rest. “

I said: “I’m tired, Jessica. Nothing you can say will alter my plans.

I have promised to marry him and I will keep my promise. We all change. He has changed. He is not the same man who came to Rosella.”

“He is the same man. I don’t forget. He stood there in the yard and the marks were on his wrists—and nothing was the same afterwards. He comes into your life. He takes you up and when he’s finished with you, you are thrown aside. He hasn’t altered. It happened to Maybella. It will happen to you.”

“I don’t intend to be thrown aside.”

“Nor did she. She thought he was wonderful at first. So will you. He can play the lover all right … even when it’s all pretence as it was with Maybella. She used to go about in a dream during those first months. She used to say to me:

“Ah, Jessie, if only I could explain to you!” I knew . even then.”

“It’s over, Jessica. There’s no point in recalling it.”

“But I want you to know. Maybella wants you to know. Well, I’ve done my duty.” She came close to the bed; the candle tipped and I thought she would set light to the bedclothes.

“Run away,” she said.

“Run away while there’s still time. Run away with Stirling.”

“You’re mad,” I said angrily.

She shook her head. Then she said sadly: “In some ways perhaps, but it’s his fault. I see this as clear as daylight. You could persuade Stirling. Try. He’d go. I’m sure of it. Don’t let that man win every time. Go away, the two of you.” She gave a hollow chuckle.

“Wouldn’t I like to see his face when he was told you’d gone?”

“Your candle grease is dripping on the quilt.”

She straightened the candle and held it under her face. In the dim light it looked like a skull. I thought: So would Maybella have looked if she had indeed come back from the dead to warn me.

“I’ve done my duty,” she said.

“If you won’t listen, that’s your lookout.”

“Go back to bed now, Jessica,” I answered.

“And do be careful with that candle.”

She went to the door and looked back at me.

“It’s you that should be careful,” she said.

Thank you for coming,” I replied, for I was sorry for her, she who had loved Lynx—she had betrayed that much to me-she who had no doubt yearned for a return of that old relationship which she believed she had once shared with him.

“I’ve done what Maybella wanted,” she muttered.

“I can do no more.”

Then she left me to lie there, thinking of what she had said, and wondering afresh about the strange man with whom I was committed to spend the rest of my life, and to ask myself what the future held. And there at the back of my mind was Stirling, who loved me perhaps but who loved Lynx better. And I?

The terrible indecision had come back. I love them both, I thought. My life would be incomplete without either of them. But they had made the decision for me. If Stirling had indeed ever thought of asking me to marry him, he was now handing me over to his father who was waiting with urgent hands and the predatory gleam in his eyes.

Adelaide made my wedding-dress. It was white silk with many frills and flounces and trimmed with rows of lace.

“It will be useful, too, when you go to England,” she said.

To England! I thought. We shall not go to England. I am going to persuade him to stay here, to drop that ridiculous notion of taking Whiteladies away from those pleasant people whom Stirling and I had glimpsed so fleetingly.

“For there,” went on Adelaide, ‘you will live in the grand manner.

Just think, you will dress for dinner every evening. You will wear velvet. I think green would become you most, Nora. You will sit at one end of the table, and my father, at the other, will be very proud of you. “

“I would rather be here.”

“But there you will live in a befitting style.”

“This style suits me.”

“You forget that your husband will be one of the richest men in England.”

“Who wants to remember that? If one has security that is enough.”

“Not for him, Nora, and his will will be yours when you are married.”

“I don’t take that view of marriage. It’s a partnership. I shall not change my personality because I’m married.”

“A husband naturally moulds his wife’s way of thinking.”

“I shall want to come to my own conclusions.”

Adelaide’s indulgent smile irritated me so I burst out:

“I don’t think he expects me to change. He became interested in me in the first place because I refused to treat him as though he were some sort of oracle, as the rest of you did.”

Adelaide did not reply but I could see that she clung to her views.

She and I made a trip to Melbourne. How very respectfully I was treated at The Lynx!

I grimaced and said to Adelaide: “I am the elect. It makes me feel holy in a way.”

We shopped lavishly and bought silks and velvets which Adelaide would make up for me. I bought a sable muff and a sable trimmed mulberry-coloured velvet cloak.

“Don’t buy too much here,” advised Adelaide.

“You’ll find everything so much more fashionable in England.”

I didn’t stress the fact that I was going to make a stand against going back to England.

We arrived back at Little Whiteladies with the goods we had bought.

“I’ve been in a torment of anxiety,” said Lynx.

“I’ll not let you go away without me again.” I was gratified and exultant because I meant so much to him.

Adelaide busied herself at once in her sewing-room. I spent a great deal of time with her—not that I cared much for sewing but at times I wanted to shut myself away from both Stirling and Lynx, so that I might contemplate this step I was taking. There in the sewing-room where the conversation was only desultory and concerned the width of a sleeve or the best way to cut a skirt, I could think of the future and try to come to some decision before I made the final step.

It was nonsense, of course. As if I could draw back! As if I wanted to! But I wished I could understand myself. If it had not been for Stirling . I might as well say: If it had not been for Lynx . No, I told myself a hundred times a day: It is Lynx. It is the strong man I need. And yet I could not get Stirling out of my thoughts.

The time was passing rapidly and I often felt that I wanted to ride out alone into the bush and that there by some miracle I should find the answer which would set my fears at rest. But Lynx had given orders that I was not to ride out alone. I discovered this one morning when I went to the stables and asked the groom to saddle my horse. He told me then that they had all been warned that I should never go riding alone. I was insistent and the groom was alarmed. I was thinking to myself: No, Lynx. I won’t be put into a cage. And you will have to know this.

I saddled the horse myself and rode out. I had not gone very far when I heard a horse galloping behind me and I saw the white horse on which he had ridden that day when he had shot Jacob Jagger.

I dug in my spurs but I could not outdistance him. He was soon beside me, his eyes gleaming with excitement. He looked like a satyr, I thought.

“Nora!” he roared.

I pulled up level with him and said: “Why the excitement?”

I gave orders that you were not to go riding alone. “

^And if I want to? “

“You won’t because you know it is against my wishes.”

“And you won’t tell your grooms to do their feeble best to stop me because you know that would be against mine.”

“You know why I don’t want you to go out riding alone.”

“Because you think I’m incompetent and fit only for … what was that horse’s name, Blundell?”

“I suffer torments of fear when you are out of my sight. I visualize all sorts of dangers which you might meet in the bush. It is for this reason that I don’t want you to go out alone.”

“Do you mean that for the rest of my life I must always be accompanied wherever I go like some young girl with her duenna?”

“It will be different when we leave here. So it is only for a short while.”

“You know,” I said slowly, ‘that I don’t want to leave here. “

“That’s because you don’t realize how much more gracious living can be.”

“I have seen the grand house of which you are thinking.” I turned to him.

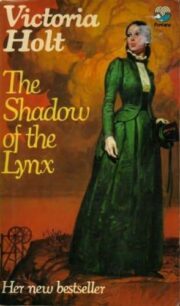

"The Shadow of the Lynx" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx" друзьям в соцсетях.