“You will have a glass of port wine.” I declined because he made it sound more like a statement than an invitation.

He lifted the decanter and poured himself another glassful. I noticed his hands then for the first time; the fingers were long and slender and on the little finger of the right hand was a ring with a carved jade stone. There was an elegance about his smallest gesture and I could imagine his living graciously in an old English country mansion.

“You wanted to know about your position here,” he said.

“You are my ward. I am your guardian. This was arranged by your father before his untimely end. He knew the hazards of this country and he often talked, in this room, of his fears and anxieties; and I gave him my promise that in the event of his death before you reached the age of twenty-one, I would take you into my care.”

“He must have had some premonition that he was going to die.”

He shook his head.

“Your father was a man who dreamed wild dreams. He was enthusiastic about them but in his heart he knew they would never come true. Deep in his mind he admitted to himself that he would never make his fortune; but it was only when he considered you that he made practical plans. You can count that as a measure of his affection for you. For you he stepped outside himself and admitted the truth as he knew it to be. So he made this bargain with me and before he died he drew up a document appointing me as your guardian. I agreed to his request—so here we are. ” Why did he choose you?”

Again that tilt of the eyebrow.

“You say that as though you think me unworthy of his trust?”

“He knew you such a short time.”

“He knew me well enough. We knew each other. Therefore, you have to accept me. You have no alternative.”

“I daresay I could earn my living.”

“In the mine … as you suggested? It is not easy for a young woman to earn a living unless it is as a housemaid or something such, which I do assure you would be a very poor one.”

“I have these shares in the mine.”

“They don’t amount to much. They wouldn’t keep you for long.”

“I would rather not have any money which belonged to me supporting a gold mine.”

“The shares can be sold. They won’t realize very much. The mine is known to be a not very profitable concern.”

“Why continue with it?”

“Hope. We always hope.”

“And meanwhile people die while you continue to hope?”

“You are thinking of your father. That is a fate which many people have met in this country. These bush rangers are everywhere. We could all encounter them.”

“I am thinking of a poor man I saw the other day. He was suffering from a lung complaint.”

“Oh … phthisis.”

“You speak as though it were about as important as a headache.”

“It’s a mining hazard.”

“Like death from bush rangers"

“Are you suggesting that I close the mine because a man is suffering from phthisis?”

“Yes.”

He laughed.

“You are a reformer, and like most reformers you understand little of what you hope to reform. If I closed my mine what would happen to all my workers? They would be starved to death in a week or so.”

“I want nothing to do with this mine.”

“Your shares shall be sold and the money banked for you. I warn you it will not be much more than a hundred pounds. And if we struck gold ..”

I don’t want anything to do with gold mining. “

He sighed and looked at me over his port, his eyes glistening.

“You are not very wise. There is a saying at home:

“Your heart rules your head.” You think with your emotions. That can get you into difficult situations and is not much help at extricating you. “

“You would be different. You think with your head.”

“That’s what heads are for.”

“And hearts?”

“To control the circulation of the blood.”

I laughed and so did he.

“Is there anything else you wish to know?” he asked.

“Yes. What am I expected to do here?”

“Do? You will help Adelaide perhaps, as a younger sister would. This is your home now. You must treat it as such.”

I looked round the room seeing it for the first time. Books lined one wall, there was an open fireplace in which logs were burning; several pictures hung on the walls and it was exactly as one would expect an English library to be. On a highly polished oak table was a chess set.

The pieces were laid out as though someone were about to play, and an exclamation escaped me because I knew that set well. It was beautiful; the pieces were made of white and brownish ivory, and there were brilliants in the crowns of the kings and queens; the squares on the board were of white and deep pink marble. I had played on it with my father.

“That is my father’s,” I accused.

“He left it here with me.”

“It would belong to me now.”

“He left it to me.”

I had stood up and went over to look at it closely. I held , the white ivory queen in my hand and was reminded so vividly of my father that I wanted to cry.

Lynx stood beside me.

“Your name is on it,” he said, pointing to one of the squares.

“We wrote our names on it when we won for the first time. That’s my grandfather. The chess set has been in the family for years.”

“Three generations,” he said.

“And the outsider.” He pointed to his own name written boldly in one of the centre squares.

“So you beat my father.”

“Now and then. And you did, too.”

“He was a fine player. I believe that when I won he allowed me to.”

“When you play with me I shall not allow you to win. I play for myself and you will play for yourself.”

You are suggesting that we play chess together? “

Why not? I enjoy the game. “

“On my father’s board,” I went on.

“It has become mine. You forgot. And why not play on it? It is a joy to touch such beautiful pieces.”

“I always understood it would be mine.”

“Let me strike a bargain with you. On the day you beat me it shall be yours.”

“Should I be asked to play for what should be mine by right?”

“It is suggested that you play to regain it ” Very well. When do we play? “

“Why not now? Would you care to?”

“Yes,” I said.

“I will play now for my chess board and men.”

“There is no time like the present. And that is another saying from home.”

We sat down opposite each other. Clearly I could see the golden eyebrows, the white slender hands with the jade ring. Stirling’s hands were slightly spatulate and I found myself continually comparing the two men. He reminded me of Stirling, yet the son was like a pale reflection of the father. I hated to admit that I had thought such a thing because it was disloyal to Stirling. Stirling is kind, I thought. This man is cruel. I understand Stirling but who could ever be sure what was behind that glittering blue barrier. He had noticed that I was looking at his hands and held them out for me to see more clearly.

“You see the carving on this ring. It’s the head of a lynx. That is what I am called. This ring is my seal. It was given me years ago by my father-in-law.”

“It’s a very fine piece of jade.”

“And a fine carving. Suitable, don’t you think?”

I nodded and reached for the white king’s pawn.

I quickly realized that I was no match for him, but I played with such concentration that again and again I foiled his efforts to checkmate me. It was a defensive game for me and it was three-quarters of an hour before he had cornered me-a climax, I sensed, he had expected to achieve in ten minutes.

“Checkmate,” he said quietly and firmly and I saw that there was no way out.

“But it was a good game, wasn’t it?” he went on.

“We must play again some time.”

“If you think me worthy,” I replied.

“I am sure you could find an opponent more in your class.”

“I like playing with you. And don’t forget you have to win that set.

Don’t forget, also, that I am not like your father. I shall give no concessions. When you win you will know that the victory was genuine I was very excited when I left him and I could not sleep for a long time that night; when I did I dreamed that all the pieces on the board came to life and the victorious king had the eyes of the Lynx.

It was October and spring was with us. The garden was beginning to look lovely. I discovered that Stirling had brought over several plants with him and we already had scarlet geraniums and purple lobelias growing on the lawn. I was wishing that I had some definite duties. I went in Adelaide’s wake helping where I could, but I felt I was very inadequate. I wanted some task which was my entire responsibility. Adelaide assured me that the help I gave in the house was invaluable, but I couldn’t help feeling that she said this out of kindness.

One day I was in the summerhouse where I had often sat while my ankle was strengthening, sitting for a moment ; because my back ached after weeding, when Jessica seemed to appear from nowhere. What a disconcerting habit this I was when people moved so noiselessly and you were suddenly aware of them standing there.

Why, Jessica! ” I cried, j ” I saw you coming from the library,” she said.

“You had been with him a long time. ”

I felt annoyed to be so spied on.

“Does that matter?” I asked coldly.

“He’s taken to you and you’re nattered, aren’t you? He takes to people and then … he’s finished with them. He doesn’t think of anything, you know, but what use they are to him.”

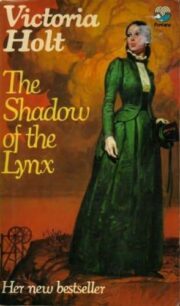

"The Shadow of the Lynx" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx" друзьям в соцсетях.