But there was a flicker of interest in his eyes as he turned to me.

“About her mount, Stirling,” he said.

“I had thought Tansy for her, but perhaps that wouldn’t be wise. “

“It’s very good of you to concern yourself,” I replied. The blue eyes were on me now.

“You’ll have to go carefully at first. This isn’t riding in Rotten Row, you know.”

“I have never ridden in Rotten Row, so I couldn’t know how different this may be.”

“No, certainly not Tansy,” he went on.

“Blundell. You’ll ride Blundell. Her mouth’s been toughened by beginners. She’ll do till you’re used to the land around here. Stirling, you might take her out tomorrow. Show her the property. Not that she’ll ride round that in a day, eh Jagger?”

Jagger laughed sycophantically.

“I’d say it was an impossibility, sir, even for you.”

“Distances are different here from where you come from. You think fifty miles is a long way, I don’t doubt. You’ll have to get used to the wide open spaces. And don’t go off by yourself. You could get lost in the bush for days and that wouldn’t be pleasant. We don’t want to have to send out search parties. We’re too busy for that.”

“I shall try not to inconvenience you in any way.” He was smiling again. I was glad that he had dropped that irritating habit of talking at me.

“I think we shall find Nora very self-sufficient,” said Adelaide.

“That’s what we have to be out here,” he replied.

“Self-sufficient.

If you are, you’ll get on. If not . then it’s better to get out. “

“Nora will be all right,” said Stirling, smiling at me reassuringly.

The conversation turned to England, and I was waiting for Stirling to mention to his father that we had seen a house called Whiteladies; but he said nothing of this. He talked of London and his father asked many questions, so the conversation flowed easily. Then he asked me about Danesworth House and I found myself talking freely. One quality he had: he seemed to be deeply interested in many things. This surprised me; I should have thought that, seeing himself as the centre of his world, the affairs of others would have seemed trivial to him. He regarded us all as lesser than himself; he was the ruler of us all, the arbiter of our lives and fates—but I was to learn that he was acutely interested in every detail of our lives. Even during that meal I became aware of the many facets of the affection between Stirling and his father and the milder emotion he felt for his daugnter. I was aware of the silent Jessica beside me who contributed little to the conversation yet made me aware of her, perhaps because I had heard that she was strange. And there was William Gardner with the fanatical gleam in his eyes when he talked of the mine where my father had worked with him. There was Jacob Jagger—and whenever I looked his way I met a bold glance of approval. Dominating that table, of course, was the man of whom I had heard so much and whose reputation I had already begun to feel was not exaggerated.

The next morning I awakened early and lay in bed thinking of the previous night until a maid—whose name I discovered to be Mary—brought in my hot water. Adelaide had told me that breakfast was between seven-thirty and nine and that I could go down at any time during that period. I rose from my bed and looked out of the window. I was looking out on a lawn, in the centre of which was a pond and in this pond was a statue; water-lilies floated there. I caught my breath in amazement. If I could have put a table there and set up a blue-and-white sunshade over it, this could be that other Whiteladies on the summer afternoon when I had seen it.

I am imagining this, I told myself. Lots of gardens have lawns and a pond with water-lilies. After all, hadn’t Adelaide told me that her father was anxious to recreate an English atmosphere? What had startled me was the coincidence of the names being the same, and the odd thing really was Stirling’s not mentioning it when we went to that other house.

I looked at my watch. I must not be late for breakfast. I thought of quiet Jessica’s gliding into the dining-room and the displeasure of Lynx, and Jessica’s indifference—or was it indifference? She had some strong feeling for Lynx. She seemed as though she hated him and was deliberately late to show her defiance. I could understand that defiance. Hadn’t I felt a little of it myself?

I found my way down to the hall, which was not used for breakfast. It was evidently not the ceremonial occasion that dinner seemed to be. At dinner, I thought, he likes to place himself at the head of the table like some baron of old while his fiefs sit in order of precedence and his serfs wait on him. At least I was above the salt. The thought amused me and I was smiling as I went into the small dining-room to women I was directed by Mary the maid.

Adelaide was already there. She smiled a good morning and asked if I had slept well. She said Stirling had already breakfasted and would come along very soon to take me out and show me round.

I replied that I was looking forward to seeing the neighbourhood and that I was deeply interested in the house. I had seen a house near Canterbury which it resembled.

“That doesn’t surprise me,” said Adelaide.

“My father designed this place. He built it ten years ago.”

“He is an architect then?”

“He is an artist, which may surprise you. When I say he designed the place, I mean that he supervised the architect and told him exactly what he wanted.”

“Your father seems remarkably endowed.”

“Unusually so. He saw houses like this when he lived in England and was determined to create a little bit of England here. He even had the gates brought from England. They are really old and were in fact taken from an English country house.”

What a lot of trouble he went to! “

“He’ll go to any amount of trouble to get what he wants.”

And here we were talking of him again. I changed the subject and asked about the garden. She was eager to show me and said that perhaps later in the day she would do so. I could probably give her advice as I was so recently from England.

Stirling came in, dressed in riding breeches and polished boots. He looked somewhat like his father—not quite so tall nor so commanding, and his greenish eyes lacked that hypnotic blue dazzle; but there could be no doubt that he was his father’s son. I felt a sudden happiness to be with him. He made me feel secure here as he had on the ship; and although I put on a bold show and was determined that no one should think I was afraid of the man my father had appointed to be my guardian, the fact remained that I was. I found him completely unpredictable and I was not at all sure of the impression I had made on him.

“Are you ready?” Stirling wanted to know.

I said I must change into my riding habit as I had not known we were to start immediately.

As soon as I had finished breakfast I went to my room and put on the riding clothes I had bought before leaving England. I remembered how shocked poor Miss Graeme had been because I had chosen green and my black riding hat had a narrow matching green ribbon about it.

When I went down to the stables Stirling looked at me with approval.

“Very elegant,” he commented.

“But it’s your skill with the horse that counts.”

I was delighted to see Jemmy in the stables, dressed in breeches and coat which were a little too large for him; but he looked very different from the shivering scrap we had found on board ship; and he had a very special smile for me, which was gratifying.

I don’t know what possessed me that morning. I knew I was wrong; but there was something in the fresh morning air and the bright sunshine which made me reckless. They were saddling Blundell, the horse he had thought fit for me to ride.

“It’s little more than a pony,” I said scornfully.

“I thought I was to have a horse. I stopped having riding lessons years ago.”

Stirling grinned and said: “You’d better have a look at Tansy.”

So I looked at Tansy—a lovely chestnut mare; and I was determined to ride her if just to show him that I was not one of the minions who accepted his word as law.

“She’s frisky,” said Stirling.

“She’s a mare, not an old nag.”

“Are you sure you can manage her?”

“My father taught me to ride when we lived in the country. I know how to manage a horse.”

“The country’s rough here. Wouldn’t you rather feel your way?”

“I’m not going to ride Blundell. I’d rather not ride at all.” } So they saddled Tansy and we set off. She was frisky and I knew I was going to need all my skill to control her; but, as I said, on that day I was reckless. For the first time since my father had died I felt a great uplifting of my spirits. I had not forgotten him; I should never do that; but it was almost as though he were beside me, rejoicing because at last I was delivered into safe hands. But it was not my guardian who gave me comfort; it was Stirling, riding beside me, so much more at home here than he had been in fie England, who made me feel secure. I knew then that I loved Stirling, and although he did not dominate my thoughts as his father did, my relationship with him brought me a deep contentment which I felt sure I could not feel with any other person. Instinctively I was aware that the affection I had for him would grow stronger every day.

“Does the sun always shine here?” I asked.

“Always.”

“Really always.”

“Almost always.”

“You’re boastful about your country.”

“Put it down to national pride. You’ll feel it after a while.”

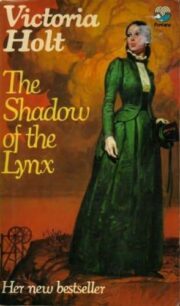

"The Shadow of the Lynx" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx" друзьям в соцсетях.