I thought of him constantly, and was troubled to think, of the punishment in store for him.

I spoke to Stirling as we sat on deck.

“I want to do something about that boy.”

“What?” he asked.

“I want to save him. He is very young. All he has done is run away. It must have been something terrible he ran from. I’m going to help him.

I must. “

“How? Will you build a ship and make him your captain?”

“Be serious. You must help me.”

“I? This has nothing to do with me.”

“It has to do with me and I’m your sister … or rather your father is my guardian. Surely that makes some sort of relationship between us?”

It doesn’t mean I have to take part in your crazy schemes. “

“If his fare was paid, if you employed him as your servant, if you took him with us, I am sure your all-powerful father could find some employment for him. You’ll help, of course.”

“I can’t think why you should assume that for one moment.”

“I don’t believe you’re as hardhearted as you would like me to believe.”

“I hope I’m a practical man.”

“Of course you are. That’s why you’ll help this boy.”

“Because you have made a rash promise you can’t keep?”

“No. But because the boy will be grateful to you forever, and in your father’s many concerns he must find it not always easy to discover good servants. The boy can be given work on your father’s property, in his hotel, or in some place in the Lynx Empire. So you see it is to your benefit to rescue him from his present dilemma.”

He laughed so much that he could not speak. I was uneasy. There was a hardness about him which I am sure he had inherited from his father. I was very worried about my poor little stowaway for whom no one from myself seemed to nave any sympathy.

“Well,” said my cabin companion, “Mr. Mullens says that this is an encouragement for people to hide themselves on ships. He said he never heard the like. We shall have half the riffraff stowing away if they are going to be rewarded for doing so.”

“One can hardly say the poor boy has been rewarded,” I retorted, ‘simply because he has been put to bed and nursed back to health. What did Mr. Mullens expect? He would be invited to walk the plank? Or perhaps be clapped into irons? These are not the days of the press gang, you know. “

She tossed her head. I was very odd, in her opinion. I suppose she discussed me with the Mullenses.

“Mr. Herrick has rescued him they say,” she smirked.

“So the boy is to become his servant.”

“Servant!” I cried.

“Doesn’t he confide in you? I heard Mr. Herrick is paying his fare, so all is well and our young rascal has been turned into an honest boy overnight.”

I smiled happily. I went to Stirling’s cabin and knocked on the door.

He was alone and I threw my arms about his neck and kissed him.

Embarrassed, he took my hands and removed them but I was too excited to feel rebuffed.

“You’ve done it, Stirling,” I cried.

“You’ve done it.”

“What are you talking about?” he demanded. But he knew.

Then he tried to excuse himself.

“He’s travelling third. It may be rough but it’s all he deserves. The fare was only seventeen guineas but naturally they don’t need that since he’s been sleeping in the lifeboat and hasn’t been fed. I’ve paid seven pounds for him and he’ll have quarters in the third class until Melbourne.”

“And then you’ll find work for him?”

“He can act as my servant until we find something for him to do.”

“Oh, Stirling, it’s wonderful! You’ve got a heart after all. I’m glad.”

“Now don’t you go endowing me with anything like that. You’ll be bitterly disappointed.”

“I know,” I replied.

“You’re hardhearted. You wouldn’t help anyone.

But you think the boy will be useful. That’s it, eh? “

That’s it,” he agreed.

“All right. Have it the way you want it. It’s the result that counts.

Poor little Jemmy! He’ll be a happy boy tonight. “

I felt close to Stirling after that. I even liked his way of pretending that he had acted from practical rather than sentimental reasons.

The rest of the journey was uneventful; and it was forty-five days after we had left Tilbury that we came to Melbourne.

It was late afternoon when we arrived and by the time we had disembarked, dusk was upon us.

I shall never forget standing there on the wharf with our bags around and Jemmy beside us in the ragged clothes which were all he had. This was my new home. I wondered what Jemmy was thinking. His dark eyes were enormous in his pale tragic young face. I reassured him and in comforting him, comforted myself.

A woman was coming towards us and I knew immediately that she was Adelaide—the one who should have come to England to fetch me.

Adelaide was plainly dressed in a cape and a hat without trimming, which was tied under her chin with a ribbon for the wind was high. I was a little disappointed; she had none of the unusual looks of Stirling and was hardly as I would have expected the Lynx’s daughter to be. The fact was she looked like a rather plain, staid countrywoman. I knew immediately that I was wrong to be disappointed because what I saw in her face was undoubtedly kindness.

“Adelaide, here’s Nora,” said Stirling.

She took my hand and kissed me coolly.

“Welcome to Melbourne, Nora,” she said.

“I hope you had a good journey.”

“Interesting,” commented Stirling.

“All things considered.”

“We’re staying at the Lynx,” she said, ‘and catching the Cobb coach tomorrow morning. “

“Goodo,” said Stirling.

“The Lynx?” I queried.

“Our father’s hotel in Collins Street,” Adelaide explained.

“I expect you’d like to be getting along. Is all the baggage here?” Her eyes had come to rest on Jemmy.

“He’s part of the baggage,” said Stirling. I frowned at him, fearing that Jemmy might be hurt to hear himself so described; but he was unaware of the slight.

“We picked him up on the ship,” went on Stirling.

“Nora thinks he should be given some work to do. “

“Have you written to our father about him?”

“No, I am leaving it to Nora to explain to him.”

Adelaide looked a little startled but I pretended to be not in the least disturbed at the prospect of explaining Jemmy to their formidable parent.

“I have a buggy waiting,” she said.

“We’ll get all this stuff sent to the hotel.” She turned to me.

“We’re some forty miles out of Melbourne, but Cobb’s are good. You can rely on Cobb’s. So we come in frequently. The men ride in but I like Cobb’s. I hope you will settle down here.”

“I hope so too,” I said.

“She will if she makes up her mind to,” said Stirling.

“She’s a very determined person.”

I walked off with Adelaide and Stirling Jemmy following. I was only vaguely aware of the bustle all around me, and the carts drawn by horses or bullocks and loaded with wool hides and meat.

“It’s a busy town,” said Adelaide.

“It’s grown quickly in the last few years. Gold has made it rich.”

“Gold!” I said a little bitterly; and she must have known that I was thinking of my father. There was something very sympathetic about this woman.

“It’s pleasant to have the town not too far away,” she said.

“I hope you won’t find us too isolated. Have you ever lived in a big city?”

“I did for a time, but I have lived in the country, too; and I felt very isolated in the place where I was first a pupil, then a teacher.”

She nodded.

“We’ll do our best to make you feel at home. Ah, here’s the buggy. I’ll tell John to see about the baggage.”

“Jemmy will help,” said Stirling.

“Let him be worth his salt. He can come along later with John and the baggage.”

So it was arranged and I rode beside Stirling and Adelaide my new brother and sister into the town of Melbourne, just as the lamp lighters riding on horseback, were lighting the street-lamps with their long torches. They sang as they worked the old songs which I had heard so often at home. I remember particularly “Early One Morning’ and ” Strawberry Fair’; and I felt that although I had journeyed thousands of miles, I was not far from home.

The hotel was full of graziers who had come in from the 48 outback to Melbourne in order to negotiate their wool. They talked loudly of prices and the state of the market; but I was more interested in another type those men with bronzed faces and calloused hands and an avid look in their eyes. They were the diggers who had found a little gold, I imagined, and came in to spend it.

We ate dinner at six o’clock in the dining-room. I sat between Adelaide and Stirling, and it was Stirling who talked of these men and pointed out those who had struck lucky and those who hoped to.

I said, “Perhaps it would have been better if gold had not been discovered here.”

“Many of the good citizens of Melbourne would agree with you,” conceded Stirling.

“People are leaving their workaday jobs to go and look for a fortune. Mind you, many of them come back disillusioned before long. They dream of the nuggets they are going to pick up and a few grains of gold dust as is all they find.”

I shivered and thought of my father and wondered if he had ever come to this place and talked as these men were talking now.

“It’s a life of hardship they lead at the diggings,” said Adelaide.

“They’d be much better off doing a useful job.”

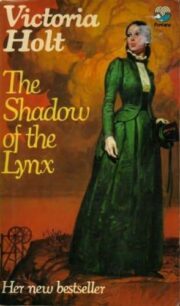

"The Shadow of the Lynx" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Shadow of the Lynx" друзьям в соцсетях.