But she didn't. Because he wasn't worth the bother.

It wasn't as though she spent her spare hours reclining on her virginal bed, dreaming impossible dreams of what have been. Instead, she had spent them draped in white cheesecloth, reciting impossible rhymes, in Lady Euphemia McPhee's private theatre in Richmond. The theatricals had provided a welcome distraction, even if the sight of St. George's spear made her think longingly of running certain people through.

Unfortunately, Lady Euphemia wasn't the only one with a taste for the stage. On a miserable, rainy Tuesday, Mary found herself slogging reluctantly up the steps of the Uppington town residence, prepared to endure that ritualized horror commonly known as a musical entertainment.

Mary's slippers squelched against the black-and-white marble tiles of the entrance hall. She had landed with both feet squarely in a puddle when her brother-in-law handed her out of the carriage. She couldn't even blame him for neglect. There had been no patch of ground that hadn't contained a puddle. The Uppingtons' footmen were having a busy time of it, scuttling about after the guests with cloths to sop up the rainwater that created gleaming slicks on the shining marble floor. One unfortunate young lady had already gone into a skid that landed her flat on an unmentionable part of her anatomy.

A perfect day for a musicale.

They were among the earliest arrivals. Although Lady Uppington had engaged a celebrated soprano for the entertainment, her daughter, Lady Henrietta, was to sing first. Loyal friend that she was, Letty had refused to risk missing so much as one syllable of her friend's song.

Mary trailed along behind her sister and brother-in-law into the music room, where Lady Uppington was bustling about, overseeing the disposal of a regiment of gilt-backed chairs, designed to cause anyone over five feet tall severe cramps in various parts of their anatomy. The prime seats, the ones towards the back that allowed for easy escape, had already been taken, one by the Dowager Duchess of Dovedale's revolting pug dog, who yipped at the newcomers as though daring them to try to move him.

Mary generally gave the Dowager Duchess of Dovedale a wide berth. The antipathy had been mutual ever since Mary's first Season when the Dowager Duchess had trained on Mary her infamous lorgnette and pronounced, "I dislike showy looks!"

Mary, younger then, and bolder, had curtsied, replying with deceptive sweetness, "Isn't that better, ma'am, than having no looks to show?"

The reference to the Dowager Duchess's granddaughter, Lady Charlotte, sweet-faced but insipid, had been too obvious to ignore. Mary and the dowager had existed in a state of mutually acknowledged enmity ever since.

If she had it to do over, Mary admitted to herself, she might be more circumspect. The dowager was a rude old bag, but she carried a great deal of weight in the segments of society that mattered to Mary. Mary had always wondered how many of the admirers who had never come up to scratch could be laid at the dowager's door. All the Dowager Duchess had to do was whisper a few words in the right ears. A discreet hint that the chit wouldn't be received — at least not in the houses that counted, of which the dowager's was still one — and the word had gone out, from anxious mother to henpecked son. There had been at least three men her first Season who might have done, older sons from solid families with enough town polish to make the thought of matrimony more pleasant than otherwise. And all three had unaccountably moved, within the space of a month, from pursuit to apologetic retreat.

Mary defiantly took a chair in the same row as the dowager. Other guests had begun to filter in, pouncing on the seats along the sides. Mary caught herself looking for a silver-headed cane among the throng of dampened shoulders and rain-spotted frocks and made herself stop. It was unlikely that Vaughn would stoop to so insipid an entertainment as a musicale, even with the city still half-empty.

Miles Dorrington tottered into the room, wearing a beatific smile and bearing a large, padded chair, which he sat down with a satisfied thump just at the end of the front row.

"Helping yourself again, I see," commented Lord Richard.

The simple words produced a palpable tension among the family circle. Lady Henrietta dropped her roll of sheet music and Lord Richard's wife produced an indiscreet but heartfelt, "Oh dear."

Dorrington looked his former friend steadily in the eye, hurt and resignation written all over his straightforward face. Lord Richard's own gaze faltered beneath his steady regard. He looked, thought Mary, almost abashed.

"I don't think Hen would appreciate the comparison," Dorrington said quietly.

"She doesn't," chimed in Henrietta, taking her husband's arm. She jabbed an index finger into her brother's side. "You, sit. And you — " Henrietta turned to her husband, who beamed at her expectantly. "You sit, too."

Miles stopped beaming.

"And if you can't speak nicely to one another, don't speak at all. That means you," she added to her brother, just in case he might be under any misapprehension.

"Bossy as ever," complained Miles good-naturedly, but he sat.

"Completely power mad," agreed Lord Richard, sitting, too.

"Do you think that means they're speaking again?" demanded Amy of her sister-in-law, in a hearty whisper that carried clear across the room.

Henrietta rolled her eyes. "At least they've moved past words of one syllable. Whatever it is, it's an improvement."

"Power mad and indiscreet," amended Lord Richard from the front row, never lifting his eyes from the polished sheen of his Hessians.

"Agreed," grunted Miles, displaying an equal fascination with his own toes.

The two men exchanged masculine nods of commiseration before quickly returning to their contemplation of their boots.

Lady Uppington regarded her offspring with an expression of maternal satisfaction. It wasn't a look Mary could ever recall seeing on her own mother's face. Mrs. Alsworthy reserved her looks of satisfaction for the milliner and the mantua-maker.

"I do wish you would consider staying," Lady Uppington said to Henrietta. "Not long," she added, in the tone of someone taking up an old argument, "but just until you've refurbished Loring House. It would be such a blessing to have all of my children under the same roof again."

"What about Charles?" Lady Henrietta pointed out, referring to her oldest brother. As heir to the marquisate, he would have been a brilliant catch, but he had already been married by the time Mary made her debut, to the unobjectionable and uninteresting daughter of a minor baron.

Lady Uppington went a guilty pink about the ears.

Henrietta seized her advantage. "Ha! You always forget about Charles."

"Nonsense," Lady Uppington declared loftily. "Charles has children of his own now. He gets his own roof."

"Hmph!" snapped the Dowager Duchess of Dovedale from the back of the room. "Roofs are wasted on the young! Leave the lot of them out in the elements. Toughen them up, I say. Most of this lot wouldn't last the week."

The dowager jabbed her cane illustratively at the pastel-clad debutantes and dandies filtering into the room. Following the line of her thrust — it was either that, or be poked in the eye by her cane — Mary saw a diamond-buckled shoe cross the threshold, a glittering counterpoint to the muddy Hessian boots of the other gentlemen. The matching shoe followed, stepping across the parquet floor with a regal precision that practically demanded a fanfare. With one hand resting casually on the silver head of his cane, Lord Vaughn paused, surveying the crowd with the bored air of a visiting emperor.

Mary's chest tightened in a way that had nothing to do with the dowager's cane "accidentally" scraping her ribs. Who would have thought that Vaughn would so lower himself as to attend a musicale? Among the chattering debutantes and tousle-headed Corinthians, his aquiline profile looked as remote and as dangerous as the portrait of a Renaissance prince.

"Caro!" Mme. Fiorila greeted Vaughn with a cry of unfeigned pleasure, and Mary felt the little quiver of anticipation that had flared up in her chest blacken and crumble.

Without missing a step or sparing a single glance for Mary, Vaughn moved smoothly to the front of the room, taking the singer by both hands and bussing her smoothly on first one cheek then the other, in the decadent European fashion. In the candlelight, the opera singer's hair glowed pure red-gold, like the molten metal in a Byzantine emperor's mint. She laughed, and murmured something in a throaty voice that was lost to Mary's ears, something intimate enough to make Vaughn raise an eyebrow in amused reply, so at ease with this woman — this opera singer — that he didn't even need to bother with words.

Caro, was it? Just how caro was he to her? Not that it mattered. Vaughn could prance through the beds of the entire Italian opera corps for all Mary cared. It was simply gauche to display such familiarity in public. One would have thought that a belted earl would have known better.

But not Vaughn. Oh no. He did as he pleased and damn the consequences, whether it was making a public spectacle of himself with a common opera singer or kissing —

"Miss Mary?"

Mary gave a decidedly undignified start at the sound of her name. A large male form cast a shadow over the program in her lap.

"Forgive me," said Mr. St. George, taking her alarmed look for one of indignation. "Miss Alsworthy, I should have said. It's simply that the other suits you so well. You look like a Madonna with your hair pulled smooth like that." His hands sketched the air in a gesture of masculine hopelessness at the intricacies of feminine coiffeurs.

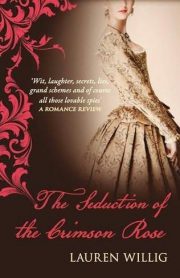

"The Seduction of the Crimson Rose" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Seduction of the Crimson Rose". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Seduction of the Crimson Rose" друзьям в соцсетях.