Ellen had set a meal in the dining room and had, greatly daring, put two lighted candles in the lovely carved gilded seventeenth-century candlesticks and had set them at either end of the Regency table; she had placed two Sheraton dining-room chairs opposite each other and the table looked delightful.

About us loomed the bookcases and chairs and two cabinets filled with porcelain and Wedgwood pottery, but the candles lighting the table shut off the rest of the room and the effect was charming.

It was like a dream. Aunt Charlotte never entertained. I wondered fleetingly what she would think if she could see us now, and I thought too how different life here would be without Aunt Charlotte. But why think of her on such an evening?

Ellen was in high spirits. I imagined her giving an account of it all to Mr. Orfey the next day. I knew she believed — for she had told me often — that it was time I had “a bit of life.” This would be in her opinion a very delectable slice of life, not just a bit.

She brought in the soup in a tureen with deep blue flower decorations and the plates matched. I caught my breath with horror that we should be using such precious plates. There was cold chicken to follow and I was thankful that Aunt Charlotte was to be away another day which would enable us to replenish the larder. Aunt Charlotte ate little herself and kept a very meager table. But Ellen had worked wonders with what she had; she had turned cold potatoes into delicious sauté and had cooked a cauliflower which she served with a cheese and chive sauce. Ellen seemed to be in possession of new powers on that night. Or perhaps I imagined that everything tasted different from what it had before.

We talked and every now and then Ellen would come in to serve, looking very pretty and excited; I was sure there had never been a happier scene in the Queen’s House, even when Queen Elizabeth was entertained here. I was full of fancies. It was as though the house approved and the alien pieces retreated as I sat in the dining room at the Regency table entertaining my guest.

There was no wine — Aunt Charlotte was a teetotaler — but that was of no importance.

He talked about the sea and foreign places and he made me believe I was there, and when he spoke of his ship and his crew I could guess what it meant to him. He was taking out a cargo of cloth and manufactured goods to Sydney and when he was there he would do a certain amount of trading with the Pacific ports before bringing wool back to England. The ship was not big; she was under a thousand tons but he would like me to see how she could cut through the water. She was in the clipper class, and you couldn’t find anything speedier than that. But he was talking too much about himself.

I protested. No. I wanted to hear it. I was fascinated. I had often been down to the docks and seen the ships there and wondered where they were going. Were they entirely cargo ships, I wanted to know.

“We take some passengers, though cargo’s the main business. As a matter of fact I have a very important gentleman sailing with me tomorrow. He’s primarily a diamond merchant and going out to look at Australian opals. He has quite a conceit of himself. There are one or two other passengers too. Passengers can present problems on ships like ours.”

And so we talked and the clocks ticked on furiously and maliciously fast.

And as we talked I said: “You haven’t told me the name of your ship.”

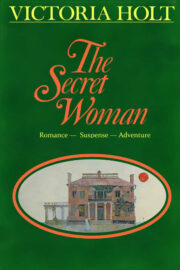

“Haven’t I? It’s The Secret Woman.”

“The Secret Woman. Why … that’s what it said on the figure which was in the desk we bought from Castle Crediton. It’s in my room. I’ll go and get it.”

I picked up the candlestick from the table. It was heavy and he took it from me. “I’ll carry it,” he said.

“Be careful with it. It’s precious.”

“Like everything in the house.”

“Well, not everything.”

And I turned and side by side we went up the stairs.

“Be careful,” I said, “as you see we’re very cluttered.”

“I understand it’s the shop window,” he replied.

“Yes,” I chattered. “I found this figure in the desk. I suppose we should have returned it to you but Aunt Charlotte said it was worthless.”

“I’m sure Aunt Charlotte, as usual, was right.”

I laughed. “She almost always is, I have to admit.” And thinking of Aunt Charlotte I marveled afresh that I could have dared to invite him to supper as I had — although Ellen had made that inevitable. But I was very willing, so it was no use blaming her. I refused to think of Aunt Charlotte at such a time; she was safely out of the way in some dingy hotel bedroom — she would never stay at the best hotels and poor Mrs. Morton was no doubt having a very trying time.

We stepped up into the room above. I always thought the house was eerie in candlelight because the furniture took on odd shapes — some grotesque, some almost human, and as they changed constantly they rarely became familiar.

“What an odd old house!” he said.

“Genuinely old,” I told him. And I laughed aloud to think of Aunt Charlotte’s verdict on Castle Crediton: Fake! He wanted to know why I laughed and I told him.

“She has the utmost contempt for fakes.”

“And you?”

I hesitated. “It would depend on the fake. Some are very clever.”

“I suppose one would have to be clever to be a successful faker.”

“I suppose so. Oh mind this, please. See how that edge of that table juts out. I didn’t see it in the shadow. It’s rather dangerous there, so near the stair.”

We had reached my bedroom.

“Miss Anna Brett slept here,” he said with mock reverence.

I was very lighthearted. “Do you think we should fix a plaque on the wall? ‘Queen Elizabeth and Anna Brett …’ Perhaps they ought to call it Anna Brett House instead of the Queen’s House.”

“It’s an excellent idea.”

“But I must show you the figure.” I took it from the drawer in which I kept it. He put down the candlestick on the dressing table and took it from me. He laughed. “It’s the figurehead of The Secret Woman,” he said.

“A figurehead.”

“Yes, no doubt there was a model of the ship and this was broken off.”

“It’s of no value?”

“None whatever. Except of course that it represents the figurehead of my ship, which might give it a little value in your eyes.”

“Yes,” I said. “It does.”

He handed it back to me and I must have held it somewhat reverently, for he laughed.

“You can take it up now and then, look at it and think of me on the bridge as it plows through the waves.”

“The Secret Woman,” I said. “It’s a strange name for a ship. Secret, and Woman. I thought all the Crediton ships were ladies.”

At that moment I heard the sound of a door being shut; I heard voices below and felt the goose pimples rise on my flesh.

“What’s wrong?” he asked and he took me by the arms and held me close to him.

I said weakly: “My aunt has come home.” My heart was beating so wildly that I could scarcely think. Why had she come home so soon? But why not? The sale had not been so interesting as she had hoped; she hated hotel bedrooms; she would not stay in one longer than she could help. It didn’t matter for what reason she had come. The point was that she was here. Perhaps at this moment she was looking at the remains of our feast … the lighted candle — only one because we had the other here — the precious china. Poor Ellen, I thought. I looked wildly about the room — at my bed, the here-today-and-gone-tomorrow pieces of furniture, and the candlelight throwing elongated shadows on the wall, the tallboy and … ourselves.

Redvers Stretton was actually alone with me in my bedroom and Aunt Charlotte was in the house! I must at least go downstairs as quickly as possible.

He understood and picked up the candle which he had put on the dressing table. But we could not hurry of course; we must pick our way carefully. As we came to the turn of the staircase and looked down at the hall, Aunt Charlotte saw us. Mrs. Morton was standing beside her; Ellen was there too, white-faced and tense.

“Anna!” said Aunt Charlotte in a voice which reverberated like thunder. “What do you think you are doing?”

The Queen’s House could never have known a more dramatic moment: Redvers towering above me — he was very tall and he was standing one stair up; the candlelight flickering; our shadows on the wall; and Aunt Charlotte standing there in her traveling cloak and bonnet, her face white with the strain of fatigue and pain, looking more than ever like a man dressed up as a woman, powerful and malevolent.

I walked down the stairs and he kept close to me.

“Captain Stretton called,” I said trying to speak naturally.

He took the matter out of my hands. “Perhaps I should explain, Miss Brett. I had heard so much of your wonderful treasure store that I could not resist coming to see it for myself. I was not expecting such hospitality.”

She was a little taken aback. Was she, too, susceptible to that charm?

She grunted and said: “You can scarcely judge antiques by candlelight.”

“Yet it must often have been by candlelight that those wonderfully wrought pieces were shown in the past, Miss Brett. I wanted to get the effect by candlelight. And Miss Brett kindly allowed me to do this.”

She was assessing his possibilities as a buyer. “What are you particularly interested in, Captain Stretton?”

I said quickly, “Captain Stretton was greatly impressed by the Levasseur cabinet.”

Aunt Charlotte grunted. “It’s a fine piece,” she said. “You’d never regret having it. It would be very easy to place if ever you wanted to pass it on.”

"The Secret Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.