It was Ellen’s dream that one day a miracle would happen and the money would come from somewhere. Where did she think? I asked her. You never knew, she replied. Aunt Charlotte had once told her that if she was still in her employ at the time of her death there might be a little something for her. That was when Ellen had hinted that she might find more congenial employment elsewhere.

“You never know,” said Ellen. “But I’m not one to like waiting for dead men’s shoes.”

I listened half-heartedly to an account of the virtues of Mr. Orfey and all the time I was thinking of the man I had met — long ago now, the son of Sir Edward and the lady’s maid. I could not understand why I continued to think of him.

I was now eighteen.

“Finishing schools,” snapped Aunt Charlotte. “That was your mother’s nonsense. And where do you think the money would come from for finishing schools? Your father’s pay stopped with him and he saved nothing. Your mother saw to that. When he died I believe he was still paying off the debts she incurred. As for your future — it’s clear that you have a flair for this profession. Mind you, you have a lot to learn … and one is always learning, but I think you might be fairly promising. So you’ll leave school after next term and begin.”

That was what I did and when a year later Miss Beringer decided to get married, the arrangement from Aunt Charlotte’s point of view was ideal. “Old fool,” said Aunt Charlotte. “At her time of life. You’d think she’d know better.” Miss Beringer might have been an old fool but her husband wasn’t and, as Aunt Charlotte told me, Miss Beringer had put a little money into the business — that was the only reason why Aunt Charlotte had taken her in — and now that man was making difficulties. There were visits from lawyers which Aunt Charlotte did not like at all, and I supposed that they came to some arrangement.

It was true that I had a flair. I could go to a sale and my eyes would alight as if by magic on the most interesting pieces. Aunt Charlotte was pleased, though she rarely showed it; she stressed my errors of judgment which were becoming rarer and lightly passed over my successes which were growing more and more frequent.

In the town we became known as Old and Young Miss Brett and I knew that it was said that it was somehow not nice for a young girl to be involved in business; it was unfeminine and I should never find a husband. I should be another Miss Charlotte Brett in a few years time.

And it was borne home to me that that was exactly what Aunt Charlotte wanted.

3

The years were passing. I was twenty-one. Aunt Charlotte had developed an unpleasant complaint which she called “rheumatics”; her limbs were becoming more and more stiff and painful, and to her fury her movements were considerably restricted.

She was the last woman to accept illness; she rebelled against it, was impatient with my suggestion that she should see a doctor and did everything she could to continue with her active life.

Her attitude was slowly changing toward me as she relied on me more. She was constantly hinting at my duty, reminding me how she had taken me in, wondering what would have become of me if when I was orphaned she had not been at hand. I became friendly with John Carmel, an antique dealer who lived in the town of Marden some ten miles inland. We had met at a sale at a manor house and become friendly. After that he was constantly calling at the Queen’s House and inviting me to accompany him to sales.

We had not progressed beyond an interested friendship when his visits ceased abruptly. I was hurt and wondered why until I overheard Ellen say to Mrs. Morton, “She gave him the order of the boot. Oh yes, she did. I heard it all. I think it a shame. After all Miss has her life to lead. There’s no reason why she should be an old maid like her.”

An old maid like her! In my cluttered room, the grandfather clock in the corner ticked maliciously. Old maid! Old maid! it jeered.

I was a prisoner in the Queen’s House. One day it might all be mine. Aunt Charlotte had hinted as much. “If you’re with me,” she had said significantly.

“You’ll be here! You’ll be here!” Why did I imagine the clock said these things to me? The date on the old grandfather was 1702, so he was old already. It was unfair, I thought, that an inanimate piece of furniture made by a man lived on and we had to die. My mother had lived for thirty years only, yet this clock had been on earth for more than a hundred and eighty years.

One should make the most of one’s time. Tick, tock! Tick, tock! All over the house. Time was flying past.

I did not believe I should ever have wanted to marry John Carmel, but Aunt Charlotte was not going to give me the chance to find out. Strangely enough when I thought of romance a vision of a laughing face with tiptilted eyes came to my mind. I was obsessed by the Creditons.

If the time came, I promised myself, that I wanted to marry, nothing and nobody should stop me.

Tick, tock! mocked the grandfather clock, but I was sure of this. I might be like Aunt Charlotte but she was a strong woman.

I was in the shop and on the point of fixing the notice on the door “If closed call at the Queen’s House”, when the bell over the door tinkled and Redvers Stretton came in. He stood smiling at me. “We’ve met before,” he said, “if I’m not mistaken.”

I was embarrassed to find myself coloring. “It was years ago,” I mumbled.

“You’ve grown up in the meantime. You were twelve at the time.” I was ridiculously delighted that he remembered. “Then it must be nine years ago.”

“You were informative then,” he said, and briefly he looked round the shop at the circular table inlaid with ivory, and the dainty set of Sheraton chairs and the tall slender Hepplewhite bookcase in a corner. “And you still are,” he added looking back at me.

I had recovered my calm. “I’m surprised that you remember. Our meeting was so brief.”

“But you are not easily forgotten, Miss … Miss … Miss Anna. Am I right?”

“You are. Did you come in to see something?”

“Yes.”

“Then perhaps I can show you.”

“I’m looking at it now, although it’s extremely uncivil of me to use that word when describing a young lady.”

“You cannot mean that you came to see me.”

“Why not?”

“It seems such an extraordinary thing to do.”

“It seems to me perfectly reasonable.”

“But suddenly … after all these years.”

“I am a sailor. I have been very little in Langmouth since our last meeting or I should have called before.”

“Well, now you are here …”

“Should I state my business and depart? Business? Of course you are a businesswoman. I must not forget that.” He wrinkled his eyes so that they were almost closed and gazed at the Hepplewhite bookcase. “You are very direct. So I must be. I’ll confess that I did not come in to buy those chairs … or that bookcase. It was merely that as I was driving past that long red wall of yours I saw the inscription on the gate, The Queens House and I remembered our meeting. Queen Elizabeth once slept over there, I said to myself, but what is far more interesting is that Miss Anna Brett sleeps there now.”

I laughed. It was a high-pitched laugh — the laughter of happiness. I had sometimes imagined I should see him again and that it would be something like this. I was becoming speedily fascinated by him. He did not seem quite real; he was like the hero of some romantic tale. He might have stepped out of one of the tapestries. He was, I was sure, a bold adventurer who roamed the seas; he was elusive for he disappeared for long periods. He might walk out of the shop and I might not see him for years and years … not until I had become Old Miss Brett. He had that quality which Ellen would describe as “larger than life.”

I said: “For how long will you be in Langmouth?”

“I sail next week.”

“For what part of the world?”

“To Australia and the Pacific ports.”

“It sounds … wonderful.”

“Do I detect signs of the wanderlust in you, Miss Anna Brett?”

“I should love to see the world. I was born in India. I thought I should go out again but my parents died and that changed everything. I came to live here, and it looks as though this is where I shall stay.”

I was surprised at myself offering so much information for which he had not asked.

He took my hand suddenly and pretended to read my palm. “You’ll travel,” he said, “far and wide.” But he wasn’t looking at my hand; he was looking at me.

I was aware of a woman standing at the window. She was a Mrs. Jennings who often came to the Queen’s House and bought very little. She was an inveterate looker-round and an infrequent buyer. I suspected it was curiosity to get her nose into other people’s houses rather than an interest in antiques which made her visit us. Now she would have seen Redvers Stretton in the shop. Had she seen him holding my hand?

The bell tinkled and she came in.

“Oh, Miss Brett, I see you have someone here. I’ll wait.”

Such alert eyes behind her pince-nez! She would be asking whether that Miss Brett had an admirer because Redvers Stretton was in that shop with her and did not appear to be buying.

Redvers looked momentarily dismayed, then with a faint lift of the shoulders said, “Madam, I was on the point of departure.”

He bowed to me and to her, and left. I was infuriated with the woman, for all she wanted was to ask the price of the bookcase. She stroked it and commented on it and hunted for signs of woodworm merely to chatter as she did so. So Redvers Stretton from the Castle was interested in an antique. He was only home for a short time she believed. There was a wild one, very different from Mr. Rex who must be a great comfort to his mother. Redvers was another kettle of fish.

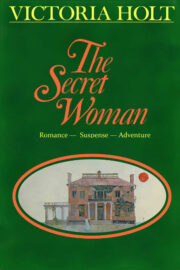

"The Secret Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.