“Do you think I shall be all right? After all, I have never had anything to do with small children. Edward will probably loathe me.”

“In any case he won’t despise you as he did poor old Beddoes. Respect is what you have to get from children. Affection follows.”

“Respect? Why should this infant respect me?”

“Because he will see in you an omniscient, omnipotent being.”

“You make me sound like a deity.”

“That’s exactly how I feel. At this moment I am proud of myself. I feel there is nothing I can’t accomplish.”

“Why? Because you have succeeded in putting a friend into a vacant post?”

“Oh, Anna, please. Not so prosaic. Let me enjoy my power for a while. Power over Lady Crediton, who sees herself if ever anyone did as the reigning sovereign.”

“At least she has to come down to earth.”

“Anna, it is good to have you here! And think — we are going to the other side of the world … together. Doesn’t that excite you?”

I admitted that it did.

The door opened and Edward peeped in.

“Come along in, my child,” cried Chantel, “and meet your new governess.”

He came — eyes alight with expectation. Oh yes, he was the Captain’s son all right. He had the same eyes which turned up slightly at the corners. My emotions were startling. I thought how happy I would have been if he were my son.

“How do you do,” I said politely, extending a hand.

He took it gravely. “How do you do, Miss … Miss.”

“Brett,” said Chantel.

“Miss Brett,” he repeated.

He was somewhat precocious. I suppose his had been a rather unusual life so far. He would have lived on this island to which we were going and then suddenly he was brought to England and the Castle.

“Are you going to teach me?” he asked.

“I am.”

“I am rather clever,” he informed me.

Chantel laughed. “Edward, that is for others to decide.”

“But I have decided.”

“You hear that, Anna, he has decided that he is rather clever. That will make your task quite easy.”

“We shall see,” I said.

He regarded me warily.

“I am going on a ship,” he said. “A big ship.”

“So are we,” Chantel reminded him.

“Shall I do lessons on the ship?”

“But of course,” I put in. “Otherwise there wouldn’t be any point in my coming.”

“I shall go on the bridge,” he said, “if we’re shipwrecked.”

“For Heaven’s sake don’t say such a thing,” cried Chantel. She turned to me. “Now you have met Master Edward, let me take you and introduce you to his Mamma. She will be most interested to meet you.”

“Will she?” asked Edward.

“Of course, she will want to see the governess of her darling child.”

“I’m not her darling child … today. I am some days though.”

That bore out what Chantel had told me of his mother.

I had met his child, now I was to meet his wife.

Chantel took me to her. She was lying in bed and I felt a twinge of emotion which I could not quite analyze. She was so beautiful. She lay back on lace-edged pillows and she wore a white silk and lace bed-jacket over her nightdress. There was a faint flush in her cheeks and her dark eyes were luminous. She breathed heavily and with some difficulty.

“This is Miss Brett, Edward’s new governess.”

“You are a friend of Nurse Loman’s.” She made it a statement rather than a question.

I agreed that I was.

“You are not much like her.” I could see that was not meant to be a compliment. She looked at Chantel and the corners of her mouth turned up slightly.

“I’m afraid not,” I said.

“Miss Brett is more serious than I,” said Chantel. “She will make an ideal governess.”

“And you had a furniture shop,” she said.

“You could call it that.”

“You couldn’t,” declared Chantel indignantly. “It was an antique business, which is very different. Only highly skilled people who know a great deal about old furniture can manage an antique shop successfully.”

“And Miss Brett managed this successfully?”

It was a sly thrust. If I had managed successfully in such a highly skilled endeavor why should I be taking the post of governess?

“Very successfully,” said Chantel. “And now that you have met Miss Brett I am going to suggest you have your tea; and after that a little rest.” She turned to me. “Mrs. Stretton had an attack yesterday … not a bad one … but still an attack. I always insist on her being very quiet after them.”

Yes, Chantel was in charge.

Edward, who had been watching the scene quietly, said that he would sit by his Mamma and tell her about the big ship they were going to sail on. But she turned her face away and Chantel said: “Come and tell me instead, Edward, while I cut your Mamma’s bread and butter.”

So I went back to my room to finish my unpacking and I felt somewhat lightheaded, as though I had strayed into some dream, completely out of touch with reality.

I stood at the turret window and looked out. I could see right across the grounds to the gorge and beyond it to where the houses of Langmouth looked like dolls’ houses in a toy town from this distance. And I thought am I really here — I, Anna Brett, in the Castle at last — governess to his son, living in close contact with his wife.

And then I thought: Was I wise to come?

Wise? By the state of my feelings I knew that I had been most unwise.

11

I settled down to my duties immediately. I found my pupil as he himself had informed me bright and eager to learn. He was wayward as most children are and while he was quite good at the lessons which appealed to him — such as geography and history — he set up a resistance against those which he did not like such as arithmetic and drawing.

“You will never be a sailor unless you learn everything,” I told him and this impressed him.

I had discovered that he could always be lured to do something if he was told it was what sailors did. I knew why.

Of course the Castle fascinated me. It was a fake, as Aunt Charlotte had said, but what a glorious fake. In building the Castle, the architects had certainly had the Normans in mind and here was displayed the massiveness of that kind of architecture. Arches were rounded, the walls very thick, the buttresses massive. The staircases which led to the turrets were typically Norman — narrow where built into the wall and widening out. One had to watch one’s step on these but I did this automatically because I never ceased to marvel at the skill in giving them such an appearance of antiquity. The Creditons had done what one would expect of them — they had combined antiquity with comfort.

I learned from Chantel that we were sailing on Serene Lady. “And I trust,” said Chantel, “that she will live up to her name. I should hate to be seasick.” We were carrying a cargo of machine tools to Australia and after a short stay there we should go on to the islands with another cargo, she supposed.

“There will only be twelve or fourteen passengers, so I heard, but I’m not at all sure. Don’t you feel excited?”

I did, of course. When I had seen Monique and the boy I had wondered about the wisdom of my coming, but I knew that if I had the opportunity to make the decision again I would do exactly the same. It was a challenge.

Chantel guessed my thoughts. “If you had stayed in England and gone on with your drab plans you would have settled down to a life of regrets. There’s nothing more boring, Anna, for you and for those about you. You would have set up an image of your Captain and enshrined it in your memory. Why? Because nothing exciting would have happened to you. When you experience something like that, the only way to get it out of your mind is to impose images over it. And one day something so wonderful will happen that it will completely obliterate it. That’s life.”

I often said to myself: “What should I do without Chantel?”

During my second week at the Castle I came face to face with the Captain.

I had walked in the grounds as far as the cliff edge and stood by the rail looking over at the sheer drop when I was aware of someone coming up behind me.

I turned and there he was.

“Miss Brett,” he said; and held out his hand.

He had changed a little. There were more lines about his eyes; there was a grimness about his lips which had not been there before. “Why … Captain Stretton.”

“You look surprised. I do live here, you know.”

“But I thought you were away.”

“I’ve been up to the London office, getting briefed for my voyage. But I’m back here now, as you see.”

“Yes,” I said, seeking to cover my embarrassment. “I see.”

“I was very sorry to hear about your aunt … and all the trouble.”

“Fortunately Nurse Loman was with me.”

“And now she has brought you here.”

“She told me that the post of governess to your … son … was vacant. I applied and was given it.”

“I’m glad,” he said.

I tried to speak lightly. “You have not really tested my qualifications yet.”

“I am sure they are … admirable. And our acquaintance was far too brief.”

“I do not see how it could have been otherwise.”

“I was going to sea, I remember. I shall never forget that night. How pleasant it was … until your aunt returned. Then the warm cozy atmosphere was gone and we had to face her disapproval.”

“That night was the beginning of her illness. She came to my room after to speak to me.”

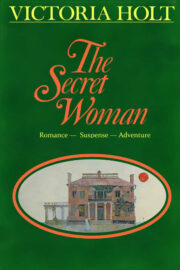

"The Secret Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.