I ran down to the door. I did not have to wend my way now that so much of the furniture had gone. We embraced. She was laughing excitedly.

“News, news!” she cried. She came into the hall and looked round it. “Why, it’s changed. It looks like a hall.”

“It’s more how it was meant to look,” I said.

“Thank goodness some of those wicked old clocks have gone. Tick tock, tick tock. I wonder they didn’t get on your nerves.”

“They’ve gone alas, for what is called ‘a song’.”

“Never mind. They’ve gone. Now listen, Anna. Something has happened.”

“I can see that.”

“What I want you to do is to read my journal and then you’ll get the picture. While you do that I’m going into the town to shop.”

“But you’ve only just come.”

“Listen. Until you’ve read that you won’t see the picture clearly. Do be sensible, Anna. I’ll be back in an hour. Not longer. So get down and read now.”

She was off again, leaving me standing there in the depleted hall, the book in my hand.

So I sat down and read; and when I came to the rather abrupt ending of her account with her in Lady Crediton’s presence making her suggestion, I knew what this implied.

I found myself staring at the few pieces that were left, and I thought irrelevantly that no one would ever buy the truly exquisite jewel cabinet, with its pewter and ivory on an ebony ground and its carved figures representing spring, summer, autumn, and winter. Who wanted such a jewel cabinet now, however beautiful? What had possessed Aunt Charlotte to spend a large sum of money to acquire something for which there were very few buyers in the world? And upstairs was the Chinese collection. Still, in the last weeks I had begun to see the daylight of solvency. I would be able to pay the debts I had inherited. It seemed that I might have a clear start.

A clear start. That was exactly what Chantel was offering me.

I could scarcely wait for her return. I asked Ellen to make a pot of tea before she left. She was not working every day now. Mr. Orfey had put his foot down. His business was improving and he wanted his wife at home to help him. It was only as a special favor that she came at all.

Ellen said she would make the tea and added that her sister often spoke very highly of Nurse Loman.

“Of course they think highly of her.”

“Edith says she’s not only a good nurse but sensible, and even her ladyship has no cause for complaint.”

I was pleased; and all the time I was thinking of leaving England, of saying goodbye to the strange solitude of the Queen’s House. Often people talked of leading a new life. It was a recognized cliché. But this would truly be a new life, a complete breakaway. Chantel was the only link with all that had happened.

But I was jumping to conclusions. Perhaps I had read Chantel’s implications incorrectly. Perhaps I was indulging in a wild dream as I had on at least one other occasion.

Ellen set the tea on a lacquered tray; she had used the Spode set. There was that delicate Georgian silver tea strainer. Oh well, it couldn’t make much difference now and this was after all a special occasion.

Ellen hung about for another glimpse of Chantel and when she had gone and we were alone in the house, Chantel began to talk.

“As soon as I heard there was a possibility of my being asked to go I thought of you, Anna. And I hated the thought of leaving you in this lonely Queen’s House with your future all unsettled. I thought I can’t do it. And then it all turned out so fortuitously … like the benign hand of fate. Poor old Beddoes being sent off like that. Of course she was quite incompetent and it would have happened sooner or later. Well then this magnificent idea came to me and I presented it to her ladyship.”

“In your journal you don’t say what she said.”

“That’s because I have a true sense of the dramatic. Don’t you realize that as you read? Now if I told you, the impact would have been lost. This was far too important. I wanted to bring the news to you myself.”

“Well, what did she say?”

“My dear, two-feet-on-the-ground-Anna, she did not dismiss it.”

“It doesn’t sound as though she were very eager to employ me.”

“Eager to employ? Lady Crediton is never eager to employ. It is for those whom she employs to be that. She is aloof from us all. She is a being from another sphere. She only feels convenience and inconvenience and she expects those about her to see that she is in a perpetual state of the former.”

She laughed, and I felt it was good to be with her again.

“Well, tell me what happened.”

“Now where did I leave off? I had implied that I would agree to travel with Mrs. Stretton if my friend could come as nurse or governess or whatever it was to the boy. And I saw at once that she thought this a convenient solution. I had so taken her off her guard by my presumption that she had not the time to compose her features into their usual mold of stern aloofness. She was pleased. It gave me the advantage.

“I said, ‘The friend to whom I refer is Miss Anna Brett.’

“‘Brett’, she said. ‘The name is familiar.’

“‘I daresay,’ I replied. ‘Miss Brett is the owner of the antique business.’

“‘Wasn’t there something unsavory happened there?’

“‘Her aunt died.’

“‘In rather odd circumstances?’

“‘It was explained at the inquest. I nursed her.’

“‘Of course.’ she said. ‘But what qualifications would this … person … have?’

“‘Miss Brett is the highly educated daughter of an Army officer. Of course it might be difficult to persuade her to come.’

“She gave a snort of a laugh. As much as to say whoever had to be persuaded to work for her!

“‘And what of this … antique business?’ she asked triumphantly. ‘Surely this young woman would not wish to give up a flourishing business to become a governess!’

“‘Lady Crediton,’ I said, ‘Miss Brett had a hard time nursing her aunt.’

“‘I thought you did that?’

“‘I was referring to the time before I came. Illness in the house is very … inconvenient … in a small house, I mean. And the strain is great. Moreover the business is too much for one to run. She is selling it and I know would like a change.’

“She had decided right from the start that she wanted you and the objections were purely habit. She merely did not want me to think that she was eager. And the outcome is that you are to present yourself for an interview tomorrow afternoon. When I return I shall tell her whether or not you are coming for the interview. I made her understand that I would have to persuade you — and that my accompanying Mrs. Stretton might well depend on your acceptance.”

“Oh, Chantel … it can’t!”

“Well I daresay I should have to go in any case. You see, it is my job and I feel that I’m beginning to understand poor Monique.”

Poor Monique! His wife! The woman to whom he had been married when he came here and led me to believe … But he didn’t. It was my foolish imaginings. But how could I look after his child?

“It sounds rather crazy,” I said. “I had thought of advertising to help an antique dealer.”

“Now how many antique dealers are looking for assistants? I know you’re knowledgeable but your sex would go against you, and it would be a chance in ten thousand if you found one.”

“It’s true,” I said. “But I need time to think.”

“There is a tide in the affairs of men

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune.”

I laughed. “And you think this is such a tide?”

“I know that you shouldn’t stay here. You’ve changed Anna. You’ve grown … morbid. Who wouldn’t, living in such a place … after all that happened?”

“I have to let the house,” I said. “I can’t sell. I never should. So much needs to be done for it. The house agent has found a man and his wife who are passionately interested in old buildings. They would have the house and look after it and do the repairs, but I should get no rent for three years during which time they undertake to do all that is necessary.”

“Well that settles it.”

“Chantel! How can it!”

“You without a roof over your head. Your tenants will do the repairs and live in the house. Of course it’s the answer.”

“I have to think about it.”

“You have to make an appointment to see Lady Crediton tomorrow. Don’t look alarmed. It wouldn’t be final even then. Come and see her. See the Castle for yourself. And think of us, Anna. And think too how lonely you would be if I went away and you joined that miserable antique dealer whom you haven’t found yet and probably never will.”

“How do you know the antique dealer will be miserable?”

“Comparatively so … compared with the excitement I’m offering you. I’ll have to go. I’ll tell Lady C. that you will come along and see her tomorrow afternoon.”

She talked of the Castle for some little time before she left. I was caught up in her excitement about the place. She had made me see it so clearly through her journal.

How quiet it was at night in the Queen’s House. The moon shone through my window filling the room with its pale light, showing the shapes in my room of those pieces of furniture which had not yet been sold.

“Tick tock, tick tock!” said the grandmother clock on the wall. Victorian. Who would want it? They had never been so popular as grandfathers.

I heard the creak of a stair, which when I was young used to make me think some ghost was walking, but it was only the shrinking of the wood. Silence all about me — and the house, now denuded of the clutter of furniture, gaining a new dignity. Who could admire the paneled walls when they were hidden by tallboys and cabinets? Who could appreciate the fine proportions of the rooms when pieces of furniture were put there as I used to say “for the time being.”

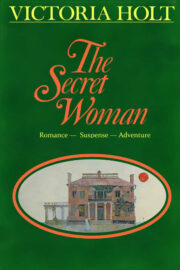

"The Secret Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.