I shook it out. “I don’t look so much like the nurse now, do I?”

“They will not recognize you.”

I looked at her startled. I knew that I was going down there; but I was surprised that she did.

I looked round the room.

“Take anything … anything,” she cried. I found a pair of golden slippers. “I bought those on my way over,” she added.

They were loose but that did not matter. They matched the green and gold robe perfectly.

“But what am I supposed to represent?” I picked up a piece of thin cardboard which Edward used for his drawing lessons — he had brought his latest picture in to show her — and twisted it into the shape of a steeple hat. “I have an idea,” I said. I took a needle and thread and in a moment I had my steeple hat. Then I took one of her sashes — a gold colored chiffon — and I draped it about the hat and let it flow down in cascades.

She was sitting up in bed rocking on her heels.

“Put on the mask, Nurse. No one will know you.”

But I had not quite finished. I had seen a silver chain girdle which she often wore about her negligee so I put it round my waist and picking up a bunch of keys which were lying on the dressing table I attached them to the girdle.

“Behold the Chatelaine of the Castle!” I said.

“The Chatelaine?” she asked. “What is this?”

“The lady of the house. The one who guards the keys.”

“Ah, that becomes you.”

I put on the mask.

“Will you dare?” she said.

There was a recklessness in me. Selina had noticed it and warned me about it. Of course I was going.

What a night it was — one I am sure I shall never forget. I was down there, among them; it was so easy for me to slip in. I felt a wild excitement grip me. Selina had said that I ought to be an actress; and I certainly acted that night. It was scarcely acting — I really felt that I was the Chatelaine of the Castle, that I was the hostess and these were my guests; I was quickly seized by a partner. I danced, resisted his attempts to discover my identity and joined in the game of mild flirtation which seemed to be the purpose of the affair.

I wondered how Rex was getting on with Helena Derringham. I could be certain that if he saw through her disguise he would do his best to avoid her.

It was almost inevitable that he should discover me in time. I was dancing with a portly Restoration nobleman when I was seized and wrested from him. Laughing I looked into the masked face and knew that my troubadour was Rex.

I thought: If I know him will he know me? But I flattered myself that I was more completely disguised. Besides, I was expecting to see him; he certainly was not expecting to see me.

“I’m sorry for the rough treatment,” he said.

“I think a serenade first of all would have been more appropriate.”

“An irresistible urge possessed me,” he said. “It was the color of your hair. It’s most unusual.”

“I shall expect you to make a ballad about it.”

“I won’t disappoint you. But I thought we should be together — after all we belong.”

“Belong?” I said.

“Just about the same period. The medieval lady … the Chatelaine of the Castle and the humble troubadour who waits outside to sing of his devotion.”

“This troubadour seems to have found his way into the Castle.” He said: “You might have come as a nurse.”

“Why?” I asked.

“You would have played the part to perfection.”

“You might have come as the shipping lord. How would that be, I wonder? A nautical uniform with a string of little ships hanging round your neck.”

“I see,” he said, “that there is no need to introduce ourselves. Did you really think I shouldn’t know you? No one else has hair that color.”

“So it was my hair which betrayed me! And what are you going to do? Dismiss me … in due course?”

“I reserve judgment.”

“Then perhaps you will allow me to retire gracefully. Tomorrow morning I shall expect to receive a summons from her ladyship. ‘Nurse, I have just heard of your most inconvenient conduct. Pray leave at once.’”

“And what of your patients if you deserted them in that cruel way?”

“I should never desert them.”

“I should hope not,” he said.

“Well, now you have caught me red-handed, as they say, there is nothing more to be said.”

“I think there is a great deal to be said. I do apologize for not sending you an invitation. You know that had those matters been left to me …”

I pretended to be relieved, but I had known all along that he was pleased I was here.

So we danced and we bantered together, and he stayed with me. It was pleasant and I know he thought so, too. But if he had forgotten Miss Derringham, I had not. In my impulsive way I asked if he knew what she was wearing. He said he had not inquired. And is there to be an announcement? I wanted to know. He replied that it certainly wouldn’t be tonight. The Derringhams were leaving on the seventh and on the night of the sixth there was to be a very grand ball. This would be more ceremonious than tonight.

“Opportunities will not be given to intruders?” I asked.

“I’m afraid not.”

“The announcement will be made, toasts will be drunk; there’ll be feasting probably in the servants’ hall; and those neither below stairs nor quite above — such as the nurse and the long suffering Miss Beddoes — perhaps even may be allowed to enter into the general rejoicing.”

“I daresay.”

“May I say now, that I wish you all the happiness you deserve.”

“How do you know that I deserve any?”

“I don’t. I wish that if you deserve it you may have it.”

He was laughing. He said: “I enjoy so much being with you.”

“Then perhaps my sins are forgiven?”

“It depends on what you have committed.”

“Well — tonight for instance. I am the uninvited guest. The Chatelaine with false keys … and not even an invitation card.”

“I told you I am pleased you came.”

“Did you tell me that?”

“If I did not I tell you now.”

“Ah, Sir Troubadour,” I said, “let us dance. And have you seen the time? I suppose they will unmask at midnight. I must disappear before the witching hour.”

“So the Chatelaine has turned into Cinderella?”

“To be turned at midnight into the humble serving wench.”

“I have never yet been aware of your humility — although I admit you have many more interesting qualities.”

“Who cares? I have always suspected the humble. Come, sir. You are not dancing. This music inspires me so and I have not much longer.”

And we danced and I knew that he was reluctant for me to leave. But I left a full twenty minutes before midnight. I had no intention of being discovered by Lady Crediton. Besides, I remembered Monique would no doubt be waiting to hear what had happened. I could never be sure what she would do. She might suddenly decide to see for herself. I pictured her coming down and looking for me and perhaps betraying me.

She was awake when I got up to her room and inclined to be sullen. Where had I been all this time? She had felt so breathless; she had thought she was going to have an attack. Wasn’t it my place to be with her? She had thought I would just go down and come straight back.

“What would have been the good of that?” I demanded. “I had to show you that I could deceive them all.”

She was immediately restored to good humor. I described the dancers, the plump Restoration knight who had flirted with me; I imitated him and invented dialogue between us. I danced about the room in my costume, reluctant to take it off.

“Oh, Nurse,” she said, “you’re not in the least like a nurse.”

“Not tonight,” I said. “I’m the Chatelaine of the Castle. Tomorrow I shall be the stern nurse. You’ll see.”

She became hysterical laughing at me; and I became rather alarmed. I gave her an opium pill and taking off my costume, I put on my nursing dress and sat by her bed until she slept.

Then I went to my room. I looked out of the window. I could hear the strains of music still. They would have unmasked; and were dancing again.

Poor Rex, I thought maliciously. He wouldn’t be able to evade Miss Derringham now.

June 7th. There is a strange flat feeling throughout the Castle. The Derringhams are leaving. Last night was the great finale, the great ceremonial ball. Everyone is talking about it. Edith came into my room on a pretext of inspecting Betsy’s work but actually to talk to me.

“It’s very surprising,” she said. “There was no announcement. Mr. Baines had made all the arrangements. We were going to celebrate in the servants’ hall naturally. They would expect it. And there was simply no announcement.”

“How very odd!” I said.

“Her ladyship is furious. She hasn’t spoken to Mr. Rex yet. But she will. As for Sir Henry he is very annoyed. He did not give Mr. Baines the usual appreciation and he has always been most generous. Mr. Baines had promised me a new gown because he was sure that after the announcement Sir Henry would be more generous than usual.”

“What a shame! And what does it mean?”

Edith came close to me. “It means that Mr. Rex did not come up to scratch as the saying goes. He just let the ball go by without asking Miss Derringham. It is most odd because everyone was expecting it.”

“It just goes to show,” I said, “that no one should ever be too sure of anything.”

With that Edith heartily agreed.

June 9th. Lady Crediton is clearly very upset. There have been “scenes” between her and Rex. The acrimonious exchanges between mother and son could not go entirely unheard by one or other of the servants and I gathered that there must have been some lively conversation behind the green baize door and at that table presided over with the utmost decorum by Baines at one end and Edith at the other. Edith of course learned a great deal and she was not averse to imparting it to me. I was very interested and rather sorry that my special status in the household prevented my joining those very entertaining meals when the conversation must have been so lively — I am sure it made up for the celebration they missed.

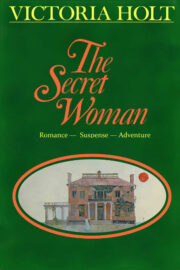

"The Secret Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.