Monique had gone to the party. She insisted. She looked strange among those elegantly dressed women. Monique would never be elegant, only colorful. I imagined that Lady Crediton would not wish her to be there. How tiresome of her, she would think, to be well enough to attend the garden party when on almost all other occasions she was so ill that Dr. Elgin had suggested they employ a nurse!

Rex was being attentive to her, which was kind of him. He was quite fond of Redvers so I supposed he thought he should be kind to his wife.

I went along to see my other patient and I found her sitting at her turret window looking down on the scene.

“How are you today?” I asked, sitting beside her.

“I’m very well, thank you, Nurse.”

It wasn’t true, of course.

“It’s colorful,” I said. “Some of the ladies’ dresses are really beautiful.”

“I see Miss Derringham … in blue there.”

I had a good look at her. It was the wrong shade of blue — too light; it made her fresh color look crude.

“There are hopes, I believe, that an announcement will be made during the visit,” I said, because I could never curb my curiosity enough to resist bringing up the subjects I wanted to talk about.

“It’s almost a certainty,” she said.

“You think Miss Derringham will accept?”

“But of course.” She looked surprised that I could suggest anyone could possibly refuse Rex. I remembered that she had been his nurse and would have loved him as a small boy.

“It will be an excellent thing to link the two companies which is what will happen naturally. It will certainly be one of the biggest companies in the Kingdom then.”

“Very good,” I said.

“She’ll be lucky. Rex was always a good boy. He deserves his good fortune. He’s worked hard. Sir Edward would be proud of him.”

“So you are hoping this marriage will take place.”

She seemed surprised that I should imply there was an element of doubt.

“Yes, it will make up for Red’s marriage. That is a disaster.”

“Well, perhaps not entirely so. Young Edward is a charming child.”

She smiled indulgently. “He’s going to be just like his father.”

It was very pleasant talking to her but I got the impression that she would give little away. There was a definite air of wariness about her. I suppose it was natural considering her past. I remember my sister Selina’s calling me the Inquisitor because she said I was completely ruthless when I was trying to prise information out of people who didn’t want to give it. I must curb my inquisitiveness. But, I assured myself, it was necessary for me to know what was in my patient’s mind; I had to save her from exerting herself, worrying about anything — and how could I do that unless I knew what she was troubled about.

Then Jane came in with a letter for her mistress.

Valerie took the letter and as her eyes fell on the envelope I saw her face turn a grayish color. I went on talking to her, pretending not to notice, but I was fully aware that she was paying little attention to what I was saying.

She was a woman under strain. Something was bothering her. I wished I knew what.

She quite clearly wanted to be alone and I could not ignore the hint she gave me; so I left her.

Ten minutes later Jane was calling me. I went back to Valerie and gave her the nitrite of amyl. It worked like a miracle and we staved off the attack while it was merely an iron vice on her arms and was over before it reached the chest and the complete agony.

I said there was no need to call Dr. Elgin; he would be looking in the next day. And I thought to myself: It was something in that letter that upset her.

The next day a most unpleasant incident occurred. I disliked the Beddoes woman right from the start, and it seems she felt similarly about me. Valerie was feeling so much better that she was taken a short walk in the garden with Jane, and I was in her room making her bed with the special bed-rest Dr. Elgin had suggested to prop her up when her breathing was difficult.

The drawer of her table was half-open and I saw a photograph album in it. I couldn’t resist taking it out and looking at it.

There were several photographs in it — mostly of the boys. Underneath each was lovingly inscribed: Redvers aged two; Rex two and a half. There was a picture of them together and again with her. She was very, very pretty in those days, but she looked a little harassed. She was obviously trying to make Redvers look where the photographers wanted him to. Rex stood leaning against her knee. It was rather charming. I was sure she loved them both dearly; I could tell by the way she spoke of them and I imagined her trying not to show favoritism to her own son; they were both Sir Edward’s children anyway.

I put the album back and as I did so I saw an envelope. I immediately thought of what had upset her and wondered if this was the letter; I couldn’t be sure because it was an ordinary white envelope like so many. I picked it up. I was holding it in my hand when I was aware that someone was in the room watching me.

That sly rather whining voice said: “I’m looking for Edward. Is he here?”

I swung round holding the letter and I was furious with myself because I knew I looked guilty. The fact was I hadn’t looked inside the envelope. I had only picked it up and I could see by her expression that she thought she had caught me red-handed.

I put the envelope back on the table as nonchalantly as I could and I said calmly that I thought Edward was in the garden. He was probably walking with his grandmother and Jane.

I felt furious with her.

I shall never forget the night of the fancy dress ball. I was very daring, but then I always had been It was Monique oddly enough who goaded me to it. I fancied she was becoming rather fond of me; perhaps she recognized in me something of a rebel like herself. I encouraged her to confide in me because my policy was that the more I knew about my patients the better. She had started to talk to me about the house where she had lived with her mother on the Island of Coralle. It sounded like a queer, shabby old mansion near the sugar plantation which her father had owned. He was dead and they had sold it now but her mother still lived in the house. As she talked she gave me an impression of lazy steamy heat. She told me how as a child she used to go down to watch the big ships come in and how the natives used to dance and sing to welcome them and to say goodbye. The great days were when the ships arrived and the stalls were set up on the waterfront with the beads and images, grass skirts and slippers, and baskets which they had made in readiness to sell to the visitors to the island. Her eyes sparkled as she talked and I said: “You miss it all.” She admitted she did. And talking she began to cough; I thought then: She would be better back there.

She was childish in lots of ways and her moods changed so rapidly that one could never be sure in one moment of abandoned laughter whether she would be on the edge of melancholy in the next. There was no contact whatever between her and Lady Crediton; she was much happier with Valerie, but then Valerie was a much more comfortable person.

She would have liked to go to the fancy dress ball but she had had an asthmatical attack that morning and even she knew it would be folly.

“How would you dress?” I asked her. She said she thought she would go as what she was, a Coralle islander. She had some lovely coral beads and she would wear flowers in her hair which would be loose about her shoulders.

“You would look magnificent, I’m sure,” I told her. “But everyone would know who you were.”

She agreed, and said: “How would you go … if you could go?”

“It would depend on what I could find to wear.”

She showed me the masks that were being worn. Edward had taken them from the big alabaster bowl in the hall and brought them to her. He had come in wearing one crying “Guess who this is, Mamma.”

“I did not have to guess,” she added.

“Nor would anyone have to if you went as you suggest,” I reminded her. “You would be betrayed at once and the whole point is to disguise your identity.”

“I should like to see you dressed up, Nurse. You could go as a nurse perhaps.”

“It would be the same thing as your going with your coral beads and flowing hair. I should be recognized immediately and drummed out as an imposter.”

She laughed immoderately. “You make me laugh, Nurse.”

“Well, it’s better than making you cry.”

I was taken with the idea of dressing up. “I wonder how I could go?” I asked. “Wouldn’t it be fun if I could so completely disguise myself that that were possible.”

She held out one of the masks to me and I put it on.

“Now you look wicked.”

“Wicked?”

“Like a temptress.”

“Rather different from my usual rôle.” I looked at myself in the glass and a great excitement possessed me.

She sat up in bed and said: “Yes, Nurse. Yes?”

“If you had a dress that I could wear …”

“You would go as an island girl?”

I opened the door of her wardrobe; I knew that she had some exotic clothes. She had bought them on the way home from Coralle at some of the eastern ports at which they had stopped. There was a robe of green and gold. I slipped out of my working dress and put it on. She clapped her hands.

“It suits you, Nurse.”

I pulled the pins out of my hair and it fell about my shoulders.

“Nurse, you are beautiful,” she cried. “Your hair is red in places.”

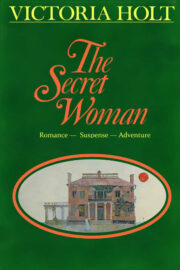

"The Secret Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.