“They would have a name like that,” said my mother. “The creditable Creditons.”

My father’s lips twitched as they did for my mother; it meant he wanted to laugh but felt it was undignified for a Major to do so. He had gained his majority since my birth and extra dignity with it. He was unapproachable, stern, honorable; and I was as proud of him as I was of my mother.

And so we came to the Queen’s House. The carriage drew up before a high red brick wall in which was a wrought-iron gate. It was an exciting moment because standing there looking up at that ancient wall one had no idea what one would find on the other side. And when the gate was opened and we went through it and it shut behind us, the feeling came to me that I had stepped into another age. I had shut out Victorian Langmouth, made prosperous by the industrious Creditons, and had stepped back three hundred years in time.

The garden ran down to the river. It was well kept, though not elaborate and not large either — I should say perhaps three quarters of an acre at most. There were two lawns divided by a path of crazy paving, and on the lawns were shrubs which would doubtless flower in spring or summer; at that time of year they were draped with spiders’ webs on which globules of moisture glistened. There was a mass of Michaelmas daisies — like lovely mauve stars, I thought them — and reddish and gold-colored chrysanthemums. The fresh smell of damp earth, grass and green foliage and the faint scent of the flowers was so different from the heavy frangipani perfume of the blooms which grew in such profusion in the hot steamy Indian air.

A path led to the house, which was of three stories — wider than it was tall; it was of the same red brick as the wall. There was an iron-studded door and beside it a heavy iron bell. The windows were latticed, and I believed that I was aware of a certain air of menace, but that may have been because I knew that I was to be left here in the charge of Aunt Charlotte while my parents went away to their gay and colorful life. That was the truth. There was no warning. I did not believe in such things.

Even my mother though was a little subdued on that occasion; but Aunt Charlotte had the power to subdue anyone.

My father — who was not nearly such a martinet as he liked to pretend — may have been aware of my fear; it may have occurred to him that I was very young to be left to the mercy of school, Aunt Charlotte and the Queen’s House. But it was no unusual fate. It was happening to young people all the time. It was, as he told me before he left me, a worthwhile experience because it taught one to be self-reliant, to face up to life, to stand on one’s own feet; he had a stock of clichés to meet occasions like this.

He tried to warn me. “This is reckoned to be a very interesting house,” he told me. “You’ll find your Aunt Charlotte an interesting woman. She runs this business … she’s clever at it. She buys and sells valuable old furniture. She’ll tell you all about it. That’s why she’s got this interesting old house. She keeps the furniture she buys here and people come here to see it. She couldn’t keep it all in her shop. And of course this sort of business is not ordinary business, so it is quite proper for Aunt Charlotte to do this. It is not as though she were selling butter or sugar over a counter.”

I was puzzled by these social differences but too overawed by my new experiences to bother with such trifles.

He pulled the rope, the old bell clanged and after a wait of some minutes the door was opened by Ellen who dropped a flustered curtsy and bade us come in.

We stepped into a dark hall; odd shapes loomed up all about us and I saw that it was not so much furnished as full of furniture. There were several grandfather clocks and some elaborate ones in ormolu; their ticking was very audible in the silence. The ticking of clocks was something I would always associate with the Queen’s House. I noticed two Chinese cabinets, some chairs and several small tables, a bookcase and desk. They were simply put there, not arranged.

Ellen had run off and a woman was coming toward us. I thought at first she was Aunt Charlotte. I should have known that her neat white cap and black bombazine dress indicated the housekeeper.

“Ah, Mrs. Morton,” said my father who knew her well. “Here we are with my daughter.”

“Madam is in her sitting room,” said Mrs. Morton. “I will inform her that you have arrived.”

“Pray do,” said my father.

My mother looked at me. “Isn’t it fascinating?” she whispered, half fearfully, which told me she didn’t think so but wanted me to. “All these priceless, precious things! Just look at that escritoire! I’ll bet it belonged to the King of the Barbarines.”

“Beth,” murmured my father in indulgent reproof.

“And look at the claws on the arms of that chair. I’m sure it means something. Just think, darling, you may discover. I’d love to know all about these lovely things.”

Mrs. Morton had returned, hands neatly folded over bombazine stomach.

“Madam wishes you to come at once to her sitting room.”

We ascended a staircase lined with tapestries and a few oil paintings which led us straight into a room which seemed to be filled with more furniture; another room led from this and from that another and this third was Aunt Charlotte’s sitting room.

And there she was — tall, gaunt, looking I thought like my father dressed up as a woman; her mid-brown hair with streaks of gray in it was pulled straight back from her big strong face and made into a knot at the back of her head. She wore a tweed skirt and jacket and a severe olive green blouse, the same color as her eyes. I knew afterward that they took their color from her clothes; and as she usually wore grays and that dark shade of green they seemed that tinge too. She was an unusual woman; she might have lived on her small income in some quiet country town, genteelly calling on her friends, leaving cards, perhaps having her own carriage, helping to organize church bazaars, doing charity work, and entertaining in a modest way. But no. Her love of beautiful furniture and porcelain was an obsession. Just as my father had stepped out of line to marry my mother, so had she with her antiques. She had become a business-woman — a strange phenomenon in this Victorian age: a woman who actually bought and sold and who knew so much about her chosen subject that she could compete with men. Later I was to see her hard face light up at the sight of some rare piece and I have heard her talk with passion about the finials on a Sheraton cabinet.

But everything was so bewildering to me on that day. The cluttered house was not like a house at all: I could not imagine it as a home. “Of course,” said my mother, “your true home is with us. This is just where you will stay during holidays. And in a few years time …”

But I could not think of the passing of the years as lightly as she could.

We did not stay overnight on that occasion, but went straight down to my school in Sherborne, where my parents put up at a hotel nearby and they stayed there until they returned to India. I was touched by this because I knew that in London my mother would have led the kind of life that she loved. “We wanted you to know we weren’t far off if school became a little trying just at first,” she told me. I liked to think that her divergence was her love for my father and myself, for one would not have expected a butterfly to be capable of so much love and understanding.

I think I began to hate Aunt Charlotte when she criticized my mother.

“Feather-brained,” she said. “I could never understand your father.”

“I could understand him,” I retorted firmly. “I could understand anyone. She is different from other people.” And I hoped my withering look conveyed that “other people” meant Aunt Charlotte.

The first year at school was the hardest to endure, but the holidays were more so. I even made plans to stow away on a ship that was going to India. I made Ellen, who accompanied me on my walks, take me down to the docks where I would gaze longingly at the ships and wonder where they were going.

“That’s a ship of the Lady Line,” Ellen would tell me proudly. “She belongs to the Creditons.” And I would gaze at her while Ellen pointed out her beauties to me. “That’s a clipper,” she would say. “One of the fastest ships that ever sailed. It goes out and brings back wool from Australia and tea from China. Oh, look at her. Did you ever see such a beautiful barque!”

Ellen prided herself on her knowledge. She was a Langmouth girl and I remembered that Langmouth owed its prosperity to the Creditons; moreover she had an added distinction: her sister Edith was a housemaid up at Castle Crediton. And she would take me to see that — but only from the outside of course — before I was many days older.

Because I dreamed of running away to India I was fascinated by the ships. It seemed romantic that they should roam round the world loading and unloading their cargoes — bananas and tea, oranges and wood-pulp for making paper in the big factory which the Creditons had founded and which, Ellen told me, provided work for many people of Langmouth. There was the grand new dock which had been recently opened by Lady Crediton herself. There was a “one,” said Ellen. She had been beside Sir Edward in everything he had done and you would hardly have expected that from a lady, would you?

I replied that I would expect anything from the Creditons.

Ellen nodded approval. I was beginning to know something of the place in which I lived. Oh, it was a sight she told me to see a ship come into harbor or sail away — to see the white canvas billowing in the wind and the gulls screaming and whirling around. I began to agree with her. There were Ladies — she told me — Mermaids and Amazons in the Lady Line. It was Sir Edward’s tribute to Lady

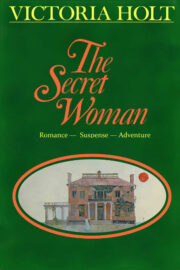

"The Secret Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.