I listened politely to my lesson in tea-making and I wondered how much information I should get from her. Not much I decided. She was not a gossip. I daresay there had been too many secrets in her own life for her to want to chatter lightly about other people’s. She must have been extraordinarily pretty when she was young. Her coloring would have been fair; her hair was still abundant though white; her eyes were very blue. Quite a beauty! No wonder Sir Edward had succumbed.

I sipped my tea. “You must know every part of the Castle,” I said. “I find its geography so difficult to learn.”

“We shouldn’t complain of that as it’s due to it that I owe the pleasure of this visit.”

I wondered what lay behind her words. I came to the conclusion that there was a depth in her which was not apparent. What a strange life hers must have been, living here under the same roof as Lady Crediton.

“Do you get many visitors?”

She shook her head. “It’s a lonely life, but I prefer it so.”

I thought, she sits and watches the world go by like a nineteenth-century Lady of Shalott.

“Rex visits me often,” she said.

“Rex. You mean …”

She nodded. “There’s only one Rex.” Her voice softened slightly. “He was always a good boy. I was nurse to them … both.”

An even more strange situation. So she was nurse to the two boys — her own and her rival’s. What a strange household; they seemed to create unnatural situations. Was that Sir Edward? I decided it was. There was a trace of mischief in the old fellow.

I pictured it. She would favor her own son. Anna’s Captain was a spoiled boy; that was why he was careless of other people’s feelings, that was why he thought he could amuse himself with Anna and never allow her to suspect that he was already married to a dusky beauty across the seas.

“I daresay you are longing to see Captain Stretton again. When will he return?”

“I’ve no idea. There was this … affair …” I waited expectantly but she did not continue. “He’s always been away for long periods since he first went to sea. He wanted to go to sea right from a baby almost. He must always be sailing his little boats in the pond.”

“I suppose they were both interested in the sea.”

“Rex was different. Rex was the clever one. Quieter too. He was the businessman.”

The man, I thought, who will multiply his father’s millions.

“They are both good boys,” she said, suddenly taking on the character of the old nurse. “And now that Redvers is away Rex comes and sees me and makes sure I know that he doesn’t forget me.”

How complex people are! I had talked to this woman for half an hour and I knew scarcely any more of her than when she was a face at the window. There was a furtiveness about her one moment and a frankness at the next when she seemed simply the nurse who had loved her charges; I imagined she would have wanted to have been fair, and knowing that naturally she would favor her own son she had tried to be equally as fond of Rex. And according to her Rex was a paragon of virtue. That was not entirely true, I was sure. I should not have been as interested in him if he were because he would have been so dull. He was far from that.

“The boys were very different in temperament,” she told me. “Red was the adventurous one. He was always talking about the sea and reading romances about it. He imagined himself another Drake. Rex was the quiet one. He had a business head on his shoulders. He was shrewd, quick to seize an advantage right from the start and when they bartered their toys and things Rex always came out best. They were so lovable, both of them … in their different ways.”

How I should have liked to pursue that topic but she was becoming wary. I sensed I should never get anything from her by pressing. My only chance was to lure her to betray herself.

One must never rush confidences. They are so much more revealing if they come out gradually. But she interested me as much as anyone in the house — except perhaps Rex. I was determined that we should become friends.

6

I found Chantel’s journal enthralling. Mine was not nearly so interesting. To read what she had written was like talking to her. She was so frank about herself that I felt my writing was stilted in comparison. The references to me and the man she called “my captain” startled me at first but then I remembered that she had said we must be absolutely frank in our journals, otherwise they were useless.

I recalled my own.

April 30th. A man called to look at the Swedish Haupt cabinet. I don’t think he was serious. I was caught in the downpour on the way back from the shop and this afternoon to my horror discovered woodworm in the Newport grandfather clock. I got to work on it at once with Mrs. Buckle.

May 1st. I think we’ve saved the clock. There was a letter from the bank manager who suggests I call. I feel very apprehensive about what he will say.

How very different from Chantel’s account of her life! I sounded so gloomy; she was so lively. I began to ask myself whether it was the different way in which we looked at life.

However the situation was melancholy. Every day I discovered that the business was more deeply in debt. After dark when I was alone in the house I would imagine Aunt Charlotte was there laughing at me, implying as she had in life: “You couldn’t do without me and I always told you so.”

People had changed toward me; I was aware of that. They looked at me furtively in the street when they thought I didn’t notice them, and I knew they were wondering: Did she have a hand in killing her aunt? She inherited the business, didn’t she, and the house?

If only they knew what anxieties I had inherited.

I tried to remember my father during that time and that he had always told me to look my troubles right in the face and stand up to them, to remember I was a soldier’s daughter.

He was right. Nothing was to be gained by pitying oneself, as I knew too well. I would see the bank manager and know the worst, and I would decide whether it was possible for me to carry on. If not? Well, I should have to make some plan, that was all. There must be something a woman of my capabilities could do. I had a fair knowledge of antique furniture, pottery, and porcelain; I was well educated. Surely there was some niche somewhere waiting for me. I shouldn’t find it by being sorry for myself. I had to go out and look for it.

At the moment I was in an unhappy period of my life. I was no longer young. Twenty-seven years old — already at the stage when one earns the title of “Old Maid.” I had never been sought in marriage. John Carmel might have asked me in due course but he had certainly been quickly frightened off by Aunt Charlotte; and as for Redvers Stretton I had behaved with the utmost naïveté and had myself imagined what did not exist. I had no one but myself to blame. I must make that clear to Chantel when I next saw her. I must try to write as interestingly, as revealingly about my life as she did about hers. It was a measure of our trust in each other, and there was no doubt that writing down one’s feelings did give one a certain solace.

I must stop my brief entries about Swedish cabinets and tall clocks. It was my feelings that she was interested in — myself — just as I was interested in her. It was a wonderful thing to have such a friend; I hoped the relationship between us would always be as it was now. I became afraid that she might leave the Castle, or perhaps I might be forced to lake a post somewhere far away. I then realized to the full what knowing her had meant to me in these difficult times.

Dear Chantel! How she had stood by me during those dreadful days which had followed Aunt Charlotte’s death. Sometimes I was convinced that she had contrived to divert suspicion from me. That was a very bold thing to do; it was what was called tampering with evidence. She was so lighthearted, so loyal in her friendship, it wouldn’t occur to her. I must write this down. No I wouldn’t because it was something too important to be written down. That was where I was not so frank as she was. When one started to write a journal one realized that there were certain things one kept back … perhaps because one didn’t really admit them to oneself. But when I think of Aunt Charlotte’s death I grew cold with horror because in spite of the button which Chantel found and the belief (which I am sure is true) that in certain circumstances people have special powers, I could never believe that Aunt Charlotte would take her own life, however great the pain she was suffering.

And yet it must have happened. How could it have been otherwise? Still everyone in that house benefited from her death — Ellen had her legacy which was more than a legacy because it was the gateway to marriage with Mr. Orfey; and Heaven knew Ellen had been waiting at the gate for a very long time. Mrs. Morton had been waiting too for the happy release from Aunt Charlotte’s service. And myself … I inherited this burden of debts and anxieties, but before Aunt Charlotte’s death I had not known they existed.

No, it was as Chantel had made them believe. I might think Aunt Charlotte would never take her life, but what human being knows all about another?

I must stop thinking of Aunt Charlotte’s death; I must face the future as my father would have done. I would go and see the bank manager; I would learn the worst and make my decision.

He sat looking at me over the tops of his glasses, pressing the tips of his fingers together, a look of mock concern on his face. I daresay he had spoken in similar strain to people before.

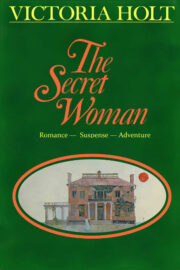

"The Secret Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.