“Mrs. Stretton’s nurse,” I told him.

He raised his eyebrows; they are light and sandy, his lashes are sandy too; he has topaz-colored eyes — yellow-brown; his nose is aquiline just like Sir Edward’s on the portrait in the gallery; his skin is very pale and his mustache has a glint of gingery gold in it.

“You are very young for such a responsibility,” he said.

“I am fully qualified.”

“I am sure you would not have been engaged unless that had been the case.”

“I am sure I should not.”

He kept his eyes on my face; I could see that he approved of my looks even if he was a little dubious about my capabilities. He asked how long I had been at the Castle and whether I was satisfied with my post. I said I was and I hoped there was no objection to my walking in the gardens. He said there was none at all and pray would I walk there whenever I wished. He would show me the walled garden and the pond; and the copse which had been planted soon after his birth; it was now a little forest of fir trees. There was a path through this which led right to the edge of the cliff. He led me there and examined the iron fence and said the gardeners had strict instructions to keep it in good repair. “It would need to be,” I remarked. There was a straight drop right down the gorse to the river. We stood leaning on the fence looking across at the houses on the opposite cliff over the bridge. There was a proud proprietorial look in his eyes and I thought of what Anna had told me about the Creditons bringing prosperity to Langmouth. He looked important then — powerful. He began to talk about Langmouth and the shipping business in such a way that he made me feel excited about it. I could see that it was his life as it must have been his father’s. I was interested in the romance of the Lady Line; and I wanted to hear as much about it as he was ready to tell.

He was ready and willing but he talked impersonally about how his father had built up the business, the days of struggle and endurance.

I said it was a wonderfully romantic story — the building of a great business from humble beginnings.

I was surprised that he should talk so freely to me on such a short acquaintance and he seemed to be too, for suddenly he changed the subject and talked of trees and garden scenery. We walked back to the sundial together and he stood beside me while we read the inscription on it. “I count only the sunny hours.”

“I must try to do the same,” I said.

“I hope all your hours will be sunny, Nurse.”

His topaz eyes were warm and friendly. I was fully aware that he was not as cold as he liked people to believe; and that he had taken quite a fancy to me.

He went in and left me in the garden. I was sure I should see him again soon. I walked round the terraces again and into the walled garden and even through the copse to the iron railings beyond which was the gorge. I was amused by the encounter and elated to find I had made an impression on him. He was rather serious, and must probably be thinking me a little frivolous because of the light way I talk, and I laugh quite frequently as I do so. It makes some people like me, but the serious one might well think me too frivolous. He was of the serious kind. I had enjoyed meeting him anyway, because he was after all the pivot around which the household revolved — and not only the household; all the power and the glory was centered on him — his father’s heir and now the source from which all blessings would flow when his mother was no more.

I went back to the sundial. This, I said to myself, is certainly one of the hours I shall count.

I looked at the watch I wore — made of turquoise and little rose diamonds, a present from Lady Henrock just before she died, and compared it with the sundial. My patient would soon be waking. I must return to my duties.

I looked up at the turret. This was not the turret in which my patient lived; it was the one at the extreme end of the west wing. I have very long sight and I distinctly saw a face at the window. For a few seconds the face was there and then it was gone.

Who on earth is that? I asked myself. One of the servants? I didn’t think so. I had not been near that turret. There was so much of the Castle I had not explored. I turned away thoughtfully; and then some impulse made me turn again and look up. There was the face again. Someone was interested enough to watch me, and rather furtively too, for no sooner had she — I knew it was a woman because I had caught a glimpse of a white cap on white hair — realized that I had seen her than she had dodged quickly back into the shadows.

Intriguing! But was not everything intriguing in Castle Crediton? But I was far more interested in my encounter with the lord of the Castle, the symbol of riches and power, than I could possibly be in a vague face at a window.

May 3rd. A perfect day with a blue sky overhead. I walked in the garden but there was no sign of Rex. I had thought that he might join me there and meet me “by accident” for I believe he is quite interested in me. But of course he would be busy at those tall offices which dominate the town. I had heard from several sources of information that he had stepped into Sir Edward’s shoes and with the help of his mother ran the business. I was a little piqued. I had imagined, with a fine conceit, that he had been interested in me. When he did not appear I started to think of the face at the window and pushed Rex out of my mind. The west turret I thought. Suppose I pretended to lose my way? It was easy enough, Heaven knew, in the Castle; and I could quite easily go up to the west wing and look round and if discovered imply that I had lost my way. I know that I am over-curious, but that is because I am so interested in people and it is my interest in them which makes me able to help them. Besides, I had an idea that to help nurse my patient I had to understand her and to do that I needed to discover everything I could about her. As everything in this house concerned her, this must.

Anyway toward late afternoon the sky became overcast, the bright sunshine had disappeared and it was clearly going to rain at any moment. The Castle was gloomy; this was the time in which I could most convincingly lose my way, so I proceeded to lose it. I mounted the spiral staircase to the west turret. Judging that it would be a replica of the quarters in which I lived, I went to a room in which I was sure was the window whence I had seen the face and opened the door. I was right. She was seated in a chair by the window.

“I … beg your pardon. Why …” I began.

She said: “You are the nurse.”

“I’ve come to the wrong turret,” I said.

“I saw you in the garden. You saw me, didn’t you?”

“Yes.”

“So you came up to see me?”

“The turrets are so much alike.”

“So it was a mistake.” She went on without waiting for me to reply which was fortunate. “How are you getting on with your patient?”

“I think we get on well as a nurse and patient.”

“Is she very sick?”

“She is better some days than others. You know who I am. May I know your name?”

“I’m Valerie Stretton.”

“Mrs. Stretton.”

“You could call me that,” she said. “I live up here now. I have my own quarters. I hardly ever see anyone. There is a staircase in the west turret down to a walled garden. It’s completely shut in. That’s why.”

“You would be Mrs. Stretton’s …”

“Mother-in-law,” she said.

“Oh, the Captain’s mother.”

“We’re a strangely complicated household, Nurse.” She laughed; it was slightly defiant laughter. I noted her high color with its tinge of purple in the temple. Heart, possibly, I thought. It was very likely that she might be my patient before long.

“Would you like a cup of tea, Nurse?”

“That is very kind of you. I should be delighted.” And I was because it would give me an opportunity of going on talking to her.

Like her daughter-in-law she had a spirit lamp on which she set a kettle to boil.

“You’re very comfortable up here, Mrs. Stretton.”

She smiled. “I couldn’t hope for more comfort. Lady Crediton is very good to me.”

“She’s a very good woman, I’m sure.” She didn’t notice the touch of irony in my voice. I must curb my tongue. I love words and they get out of control. I wanted to win her confidence because she was the mother of one of those two boys born almost simultaneously of the same father but by different women and under the same roof, which could have been a situation from one of Gilbert and Sullivan’s operas — except of course that they were never improper and this was decidedly so. I must go along and have a look at old Sir Edward’s portrait in the gallery. What a character he must have been! What a pity that he was not alive today! I was sure he would have made the Castle even more exciting than it was.

She asked me how I was getting on and if I enjoyed my work. It must be tremendously interesting, but she feared I must find it trying at times. Another, I thought, who doesn’t like my naughty patient.

I said I was used to coping with patients and didn’t anticipate that my present one would be any more trying than others I had experienced.

“She should never have come here,” Valerie Stretton said vehemently. “She should have stayed where she belonged.”

“The climate is not good for her, I admit,” I said. “But as this is her husband’s home perhaps she prefers to be here, and happiness is one of the best of all healers.”

She made the tea. “I blend it myself,” she said. “A little Indian mingled with the Earl Grey and of course the secret is to warm the pot and keep it dry; and the water must have just come to the boil.”

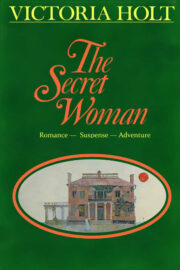

"The Secret Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.