Aunt Charlotte had grown worse; she could not move from her bed. The injury to her spine had aggravated her complaint, said Dr. Elgin. Her bedroom had become an office. She still kept a tight hold on the books and I was never allowed to see them; but I was taking over all the selling and a great deal of the buying, though everything had to be submitted to her first and accounts passed through her hands. I was very busy. I devoted myself passionately to my work and if ever Ellen or Mrs. Buckle started to talk about what was happening up at Castle Crediton I implied that I was not interested.

One day Dr. Elgin asked to see me; he had just come down from Aunt Charlotte’s room.

He said: “She’s getting worse. You can’t manage her without help. There’ll come a time very soon when she’ll be completely bedridden. I suggest you have a nurse.”

I could see the point of this but it was, I said, a matter I should have to discuss with my aunt.

“Do so,” said the doctor. “And impress on her that you can’t do all that you do and be an attendant in the sick room. She needs a trained nurse.”

Aunt Charlotte was against the idea at first but eventually gave in. And then everything changed because Chantel Loman had arrived.

4

How can I describe Chantel? She was dainty and reminded me of a Dresden china figure. She had that lovely shade of hair made famous by Titian, with rather heavy brows and dark lashes; her eyes were a decided shade of green and I thought her coloring the most arresting I had ever seen. She had a straight little nose and a delicately colored complexion which, with her slender figure, gave her the Dresden look. If she had a fault it was the smallness of her mouth but I thought — and this had occurred to me with some of the finest works of art I handled — that it was the slight imperfection which added something to beauty. Perfect beauty in art and nature could become monotonous; that little difference made it exciting. And that was how Chantel seemed to me.

When she first came into the Queen’s House and sat on the carved Restoration chair which happened to be in the hall at that time, I thought: “She’ll never stay here. She’ll not come in the first place.”

But I was wrong. She said afterward that the place fascinated her, as I did. I looked so … forbidding. A regular old maid in my tweed skirt and jacket and my very severe blouse and my really lovely hair pulled back and screwed up in a way which destroyed its beauty and was criminal.

Chantel talked like that — underlining certain words and she had a way of laughing at the end of a sentence as though she were laughing at herself. Anyone less like a nurse I could not imagine.

I took her up to Aunt Charlotte and oddly enough — or though perhaps I should say naturally enough — Aunt Charlotte took a fancy to her on the spot. Chantel charmed naturally and easily, I told Ellen.

“She’s a real beauty,” said Ellen. “Things will be different now she’s come.”

And they were. She was bright and efficient. Even Aunt Charlotte grumbled less. Chantel was interested in the house and explored it. She told me later that she thought it was the most interesting house she had ever been in.

When Aunt Charlotte had been made comfortable for the night Chantel would come and sit in my room and talk. I think she was glad to have someone more or less her own age in the house. I was twenty-six and she was twenty-two; but she had lived a more interesting life, had traveled with her last patient a little and seemed to me a woman of the world.

I felt happier than I had for a long time and so was the entire household. Ellen was interested in her and I believe confided in her about Mr. Orfey. Even Mrs. Morton was more communicative with her than she had ever been with me, for it was Chantel who told me that Mrs. Morton had a daughter who was a cripple and lived with Mrs. Morton’s unmarried sister five miles from Langmouth. That was where she went on her days off; and she had come to the Queen’s House and endured the whims of Aunt Charlotte and the lack of comforts because it enabled her to be near her daughter. She was waiting for the day she would retire and they would live together.

“Fancy her telling you all that,” I cried. “How did you manage to get her to talk?”

“People do talk to me,” said Chantel.

She would stand at my window looking out on the garden and the river and say that it was all fascinating. She was vitally interested in everything and everybody. She even learned something about antiques. “The money they must represent,” she said.

“But they have to be bought first,” I explained to her. “And some of them have not been paid for. Aunt Charlotte merely houses them and gets a commission if she makes a sale.”

“What a clever creature you are!” she said admiringly.

“You have your profession which is no doubt more useful.”

She grimaced. At times she reminded me of my mother; but she was efficient as my mother would never have been.

“Preserving lovely old tables and chairs might be more useful than preserving some fractious invalids. I’ve had some horrors I can tell you.”

Her conversation was amusing. She told me she had been brought up in a vicarage. “I know now why people say poor as church mice. That’s how poor we were. All that economy. It was soul-destroying, Anna.” We had quickly come to Christian names, and hers was so pretty I said it was a shame not to use it. “There was Papa saving the souls of his parishioners while his poor children had to live on bread and dripping. Ugh! Our mother was dead — died with the birth of the youngest, myself. There were five of us.”

“How wonderful to have so many brothers and sisters.”

“Not so wonderful when you’re poor. We all decided to have professions and I chose nursing because, as I said to Selina, my eldest sister, that will take me into the houses of the rich and at least I can catch the crumbs that fall from the rich man’s table.”

“And you came here!”

“I like it here,” she said. “The place excites me.”

“At least we shan’t give you bread and dripping.”

“I shouldn’t mind if you did. It would be worth it to be here. It’s a wonderful house, full of strange things, and you are by no means ordinary, nor is Miss Brett. That is what is good about this profession of mine. You never know where it will lead you.”

Her sparkling green eyes reminded me of emeralds.

I said: “I should have thought anyone as beautiful as you would be married.”

She smiled obliquely. “I have had offers.”

“But you’ve never been in love,” I said.

“No. Have you?”

That brought the color flooding my cheeks; and before I could prevent myself I was telling her about Redvers Stretton.

“A roving Casanova,” she said. “I wish I’d been here then. I would have warned you.”

“How would you have known that he had a wife abroad?”

“I would have found out, never fear. My poor dear Anna, you have to see it as a lucky escape.” Her eyes shone excitedly. “Think of what might have happened.”

“What?” I demanded.

“He might have offered marriage and seduced you.”

“What nonsense! It was all my fault really. He never gave the slightest indication that he was … interested in me. It was my foolish imagination.”

She did not answer but from that moment she became very interested in Castle Crediton. I used to hear her talking about it and the Creditons with Ellen.

My relationship with Ellen had changed; Ellen was far more interested in Chantel than in me. I could understand it. She was wonderful. By a deft touch of flattery she could put even Aunt Charlotte in a good mood. Her charm lay in her interest in people; she was avidly curious. After Ellen’s day off she would go to the kitchen to prepare a tray for Aunt Charlotte and I would hear them laughing together.

Mrs. Buckle said: “That Nurse Loman’s a real bit of sunshine in the house.”

I thought how right she was.

It was Chantel who had the idea about our journals. Life, she said, was full of interest.

“Some people’s,” I said.

“All people’s,” she corrected me.

“Nothing happens here,” I told her. “I lose count of the days.”

“That shows you should keep a journal and write everything down. I have an idea. We both will and we’ll read each other’s. It’ll be such fun because, you see, living as close as we do we shall be recording the same events. We’ll see them through each other’s eyes.”

“A journal,” I said. “I’d never have time.”

“Oh yes, you would. An absolutely truthful journal. I insist. You’ll be surprised what it will do for you.”

And that was how we began to keep our journals.

She was right, as she always seemed to be. Life did take on a new aspect. Events seemed less trivial; and it was interesting to see how differently we recorded them. She colored everything with her own personality and my account seemed drab in comparison. She saw people differently, made them more interesting; even Aunt Charlotte emerged as quite likable in her hands.

We had a great deal of pleasure out of our journals. The important thing was to put down exactly what one felt, said Chantel. “I mean, Anna, if you feel you hate me over something, you shouldn’t mince your words. What’s the good of a journal that’s not truthful?”

So I used to write as though I were talking to myself and every week we would exchange our journals and see exactly how the other had felt.

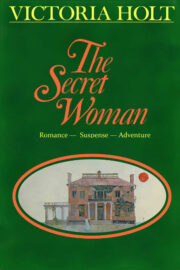

"The Secret Woman" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret Woman". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret Woman" друзьям в соцсетях.