Marston’s comings and goings from the docks had not escaped the notice of the Assistant to the Minister of Police. Marston claimed the call of his French blood drew him back to the service of his homeland. Others claimed it had been the stronger siren call of higher pay. Delaroche considered a third explanation. How easy it would be for a man to claim a change of allegiance, infiltrate the highest reaches of government . . . all the while reporting to his former masters.

Marston had used his acquaintance with that idiot brother-in-law of the consul’s, Joachim Murat, to propel himself into the inner circles at the Tuilleries. The friendship, Delaroche gathered, had been founded on a basis of imbibing, gaming, and wenching. Delaroche himself had no use for such pastimes. He had heard, however, that they provided an excellent pretense under which to gather intelligence.

Delaroche’s nostrils flared scornfully. Amateurs!

For a moment, Delaroche toyed with the delicious notion of subverting the Purple Gentian to Bonaparte’s cause. Georges Marston was a soldier of fortune. If he were the Purple Gentian, one need only find out what the British were paying him and double it. Throw in a commission in the French army—colonel, perhaps?—marry him off to one of Mme Bonaparte’s ladies-in-waiting, and Marston would be theirs for life. What a coup that would be! PURPLE GENTIAN DESERTS TO BONAPARTE the headlines on those despicable English news sheets would read.

Such an outcome might almost be more pleasurable than killing him. Delaroche caressed the blade of the letter opener with one scarred finger. Almost.

Ah, well, one could always subvert the man, enjoy the embarrassment of the English for a few weeks, and then arrange for a little accident to befall the newest colonel in Bonaparte’s forces.

Regretfully putting aside the knife with one last, loving caress, Delaroche penned a third name, jotting the characters tersely onto the page: Edouard de Balcourt.

Underneath his thoroughly French name, Balcourt was half English. It had not escaped the attention of the Ministry of Police that Balcourt had been sending couriers into England over the years under the pretense of letters to his sister. Sister, ha! True, the girl existed, but what man went to such trouble over a mere sister? Delaroche hadn’t given his own sister a thought since she married that butcher in Rouen fifteen years ago.

Balcourt had seen his father’s head roll into the straw below the guillotine (a particularly fine day for an execution, Delaroche recalled fondly); his estates had been looted, his vineyards torched. All in the interests of the Republic, of course, but someone without civic spirit might take such acts as a personal affront.

Balcourt’s gaudy waistcoats, his overlarge cravats . . . No French tailor would produce clothing that execrable unless it was deliberate. Those cravats bespoke a man who had something to hide.

But no cravat in France was large enough to shield Balcourt from the all-seeing eyes of the Ministry of Police.

Without hesitation, Delaroche continued on to his fourth and final suspect, Augustus Whittlesby. Whittlesby proclaimed himself a romantic poet seeking inspiration among the splendors of la belle France. He could usually be found languishing among the inns of the Latin quarter, flowing white shirt askew, one pale hand pressed to his brow, the other wrapped around a carafe of burgundy. When Delaroche had asked him sharply if he suffered a medical condition (Whittlesby having inconveniently swooned onto his boots just as Delaroche was preparing to follow a suspect), Whittlesby had declared in dramatic tones that he was overcome, not with any weakness of the body, but with the soul-searing joys of poetic inspiration. He had then, with Delaroche held captive by his boot-tops, insisted on reciting an impromptu ode to the cobblestones of Paris that began, “Hail to thee, thou sylvan stones!/ Upon whose adamantine brilliance tread many feet!/ Tread there more feet! More happy, happy feet!/ In boots with merry tassels and polish bright/ That never know the scum of a dirt road.” The happy, happy feet had trotted along the merry, merry cobbles for twenty-five further stanzas, while Delaroche’s feet had remained very unhappily immobile on cobbles more muddy than merry.

Delaroche eyed his letter opener speculatively. Perhaps Whittlesby might be dispatched even if not identified as the Purple Gentian.

Delaroche was about to shout to the sentry to summon him four agents, when a sudden recollection barreled out of the miscellany of information he acquired every day, giving him pause. Yesterday, another Englishman had returned to Paris. That same Englishman had left Paris directly following the Purple Gentian’s theft of Delaroche’s dossiers.

This man had come to Delaroche’s attention before. That alone was little distinction, as most of Paris had come to Delaroche’s attention at some point. But Delaroche’s attention had been so arrested that he had cornered the gentleman in question at no fewer than seven of Mme Bonaparte’s receptions, and personally shadowed him for over a fortnight. Delaroche’s efforts had proven fruitless (unless one counted a new understanding of several passages in Homer). In the end, Delaroche had reluctantly dismissed him because, to all appearances, he was exactly what he claimed to be: a gentleman scholar with an utter disregard for current affairs and a knowledge of the classics to make a schoolmaster weep with joy. Yet . . . the coincidence of the dates tugged at Delaroche with almost physical force.

Before calling for his spies, Delaroche penned one last name.

Lord Richard Selwick.

Chapter Thirteen

Lord Richard Selwick regarded the assemblage in the Yellow Salon of the Tuilleries Palace with a yawn. Not terribly much, it seemed, had changed in his two weeks’ absence. Richard resisted the urge to tug at his carefully arranged neckcloth; the room was uncomfortably warm with the heat of too many bodies and too many candles. Scantily clad women drifted from cluster to cluster like moths flitting from lamp to lamp—only, Richard noted with some amusement, unlike the insects, the ladies stayed as far away as possible from the telling light of the flames. Josephine, herself older than she liked to admit, had draped the candle sconces and mirrors in gauze, but even the gentle light betrayed cheeks layered with rouge.

A burst of raucous laughter sounded from across the room. Over the curled and turbaned heads of the crowd, Richard trained his quizzing glass on the source of the sound. Ah, Marston. Between his long, curly sideburns, Marston’s face was flushed with heat and drink. He had one arm propped against the mantelpiece; the other was gesticulating with a snifter of brandy to an appreciative audience composed of Murat and a couple of other chaps in military attire hung with far more medals than their age made likely. Richard considered wandering over to investigate, but decided he needn’t push his way through the crush of perfumed bodies just yet. From the sound of the guffaws wafting from the fireplace, Marston was telling jokes, not deep secrets.

Richard let his quizzing glass trail about the room. The usual gossip, the usual flirtations, the usual crowd of underdressed women and overdressed men. It was enough to make one understand why the French were always moaning on and on about ennui.

“Who are those provincials with Balcourt?” Vivant Denon elbowed Richard in his ribs. “The two young ones are not ill-favored, but those clothes!”

Denon, who had headed the scholars in Egypt, and was at present in charge of setting up Bonaparte’s new museum in the Louvre Palace, had very decided ideas about aesthetics. Especially regarding women. Denon’s own elegantly attired mistress, Mme de Kremy, was just two yards away, occasionally sending steamy looks in Denon’s direction. At least Richard hoped they had been intended for Denon; Mme de Kremy was not at all the sort of woman he preferred.

As for the sort of woman Richard preferred . . . Following Denon’s gaze, Richard sighted Amy Balcourt, one gloved hand lightly resting on her brother’s arm. Richard’s ennui evaporated in an instant. With some amusement, Richard noted that Amy fidgeted like a horse at the start of the Derby, straining to see around her brother into the crowded salon. Balcourt had paused in the doorway to exchange pleasantries with Laure Junot, and Amy was not weathering the delay well. As Richard watched, Jane, standing behind Amy with Miss Gwen, leaned forward and whispered something in Amy’s ear, to which Amy responded with a quick, rueful smile. Richard started to smile back at her, even though the look had not been intended for him.

“They should hand all young women from the provinces a fashion plate and march them to the dressmaker before they let them into the Tuilleries!” Denon was saying.

“These have the handicap of being from England,” Richard commented dryly.

“Ah, that explains it!” Denon stared unabashedly at Amy and Jane. “Those heavy fabrics, those boxy styles, they are so sadly English. As charity to them, we ought to send a boatload of dressmakers across the Channel.”

Richard wouldn’t have called Amy’s form boxy. True, Amy’s dress didn’t hug her body like those of the Frenchwomen, who wore their filmy dresses with only a single slip, dampened to make the fabric cling to their legs (more than one woman had caught her death of cold by doing so in winter, but Frenchwomen seemed to agree that style was worth the risk of death). Instead, Amy’s dress fell gracefully from its high waist, lightly skimming her hips, merely hinting at the feminine form beneath. Next to the plain white lawn worn by the other women, the satin of Amy’s dress glimmered in the candlelight like snow seen by moonlight.

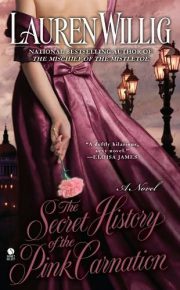

"The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Secret History of the Pink Carnation" друзьям в соцсетях.